By Hugh Harvey, MD.

In late 2016 Prof Geoffrey Hinton, the godfather of neural networks, said that it’s “quite obvious that we should stop training radiologists” as image perception algorithms are very soon going to be demonstrably better than humans. Radiologists are, he said, “the coyote already over the edge of the cliff who hasn’t yet looked down”.

This kick-started a hype-wave of biblical proportions that is still rolling to this day, and shows no signs of breaking just yet. In my opinion, although this wave of enthusiasm and optimism has successfully brought radiology artificial intelligence to the forefront of people’s imaginations, and immense amounts of funding with it, it has also done untold harm by over-inflating the expectations of policy and decision makers, and is having tangible knock-on effects on recruitment as disillusioned junior doctors start believing that machines are indeed replacing humans and so they shouldn’t bother applying to become radiologists. It is hard to imagine a more damaging statement occurring at a time when the crisis in radiology staffing, especially acute in the UK, is threatening to destabilise entire hospital systems.

You see, without radiologists, a hospital simply can not function. I would conservatively estimate that over 95% of patients who enter a hospital will have some form of medical imaging, and as the number of patients grows, so does demand for imaging services. Not only that, but as imaging becomes recognised as the crux of most diagnoses, most treatment pathways and most outcome measurements, we are already seeing what looks like an almost exponential rise in demand for medical imaging, and ergo — radiologists. This is starkly counter-balanced by sensationalist headlines along the lines of “machine beats radiologist” which only serve to further misinform the general public on the real state of AI currently, misleading them into thinking radiologists’ days are numbered.

However infatuated or convinced you are about the possibilities of AI and automation, it is simply not realistic to expect it to entirely replace human radiologists in the near future, if at all. My estimate is 10 years until we see AI in routine NHS practice — and my opinion here is now a matter of parliamentary record! I know this may be controversial given the amount of hope and hype currently, and maybe even surprising from someone like me who has essentially dedicated their career to AI in radiology, but I believe it is absolutely crucial to have sensible discussions on the future of the profession, rather than listen solely to silicon valley evangelists and the media who, let’s admit it, haven’t a clue what it is radiologists actually do, and just love to overplay the power of what they are peddling.

In this article I’m going to attempt to break down the three main reasons why diagnostic radiologists are safe (as long as they transform alongside technology), and even argue why we need to train even more.

Reason 1. Radiologists don’t just look at images.

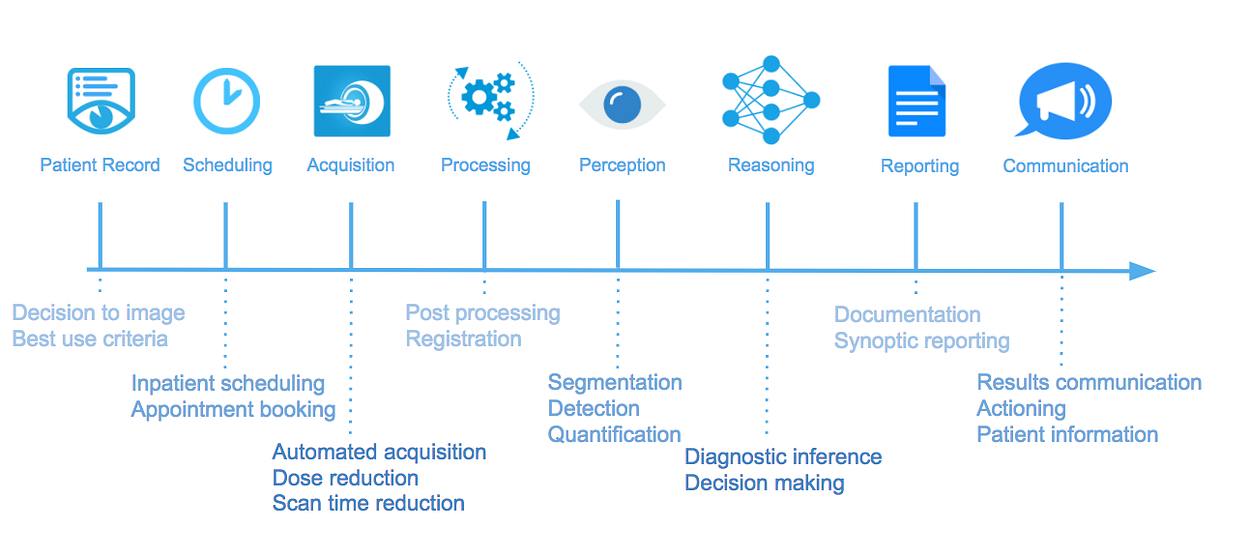

If there is one thing that I would like to scream at anyone who says AI will replace radiologists, it is this — radiologists do not just look at pictures! All of the media hype about AI in radiology pertains to image perception only and, as clearly visualised in my diagram below, image perception is not the totality of what a human radiologist does in their day job. Additionally, the above graphic only depicts a diagnostic workflow, and completely omits patient-facing work (ultrasound, fluoroscopy, biopsy, drains etc), multi-disciplinary work such as tumour boards, teaching and training, audit, and discrepancy review that a diagnostic radiologist also does on a regular basis. I know of no radiologist who only does diagnostic reporting as a full-time job. (There’s even the separate profession of interventional radiology, more akin to surgery than image perception, also a profession suffering a workforce crisis, that is less likely to benefit from AI systems).

The diagnostic radiology workflow can be simplified into its component steps as visualised above: from patient presentation and history which leads to decision-making on whether or not to image, and what type of imaging to perform, to scheduling the imaging, and automating or standardising image acquisition. Once imaging is done, algorithms will increasingly post-process images ready for interpretation by other algorithms, registering data sets across longitudinal timeframes, improving image quality, segmenting anatomy and performing detection and quantification of biomarkers. At present, diagnostic reasoning seems the toughest nut to crack and is where humans will maintain most presence. This will be aided by the introduction of smart reporting software, standardised templates and machine-readable outputs making data amenable to further algorithmic training to better inform future decision-making software. Finally, communication of the report can be semi-automated via language translation or lay-translation, and augmented presentation of results in a meaningful form to other clinicians or patients can also be accomplished. And this is only for starters…

While artificial intelligence can absolutely play a part in each of the steps in this diagnostic workflow, and even replace a human in some of them (like scheduling) it simply cannot replace a radiologist entirely. That is unless we miraculously develop a complete end-to-end system that has oversight and control over the entire diagnostic pathway. This to me is a pipe dream, especially given the current state-of-the-art in AI systems which are only just barely making it into clinical workflows at present, none of which are anywhere close to replacing radiologists’ image perception work in any significant sense.

Reason 2. Humans will always maintain ultimate responsibility

In 2017 not one single human being died in a commercial airplane accident. This amazing success story is in part due to the implementation of high-tech systems that automate many of the safety oversight tasks normally conducted by human staff, including, but not limited to, collision avoidance systems, advanced ground proximity warning systems, and improved air traffic control systems. It is also in large part due to better training, awareness of safety issues and alerting/escalation of concerns by human pilots and other ancillary aviation staff.

Where automation has evolved over the past couple of decades, humans have been given more freedom to communicate safety issues, with more time to react to increasing amounts of useful information, all supported by a cohesive environment of industry-led safety awareness. The most crucial fact, however is that there has been zero decrease in the number of commercial pilots — in fact, quite the opposite. Airlines are reporting a shortage of trained pilots, and there are growing concerns over a predicted need to more than double the global number. You see, as safety improves, costs reduce, flying becomes more popular, passenger numbers increase, it stands to reason that more planes will be required.

Medicine is often compared to aviation, sometimes inappropriately and often inaccurately. However, I feel there are some overlapping key features for both industries. For starters, both are focussed primarily on maintaining the safety of humans while getting them from point A to point B, either geographically or systematically. Both also traditionally rely on human expertise and high level training to oversee the processes involved. Both also have seen huge strides in automation over the past decade, and of course both stand to benefit significantly from artificially intelligent systems taking more and more of the cognitive workload and mundane tasks away from humans. But most importantly — in both industries, humans are categorically not being replaced.

The reason is simple — legal responsibility. It is almost unfathomable to imagine the owner of an AI system opting to take full legal responsibility of a machine output when human lives are on the line. No airline has come close to flying a commercial plane entirely without pilots, and if it does, I would bet that the insurance policies will be so huge it will likely not make it worth it for general commercial flying (however, I concede it may be seen on private or military flights, for instance). What we will likely see is ‘drone’ piloting of commercial flights — pilots seated squarely on terra firma but remotely monitoring everything happening on a plane as it soars across the globe. In fact, experiments are already being planned for remote piloting, with mixed reactions from the general public.

In medicine, it is currently far, far, far easier to simply limit an AI system to providing ‘decision support’ and leave all ultimate ‘decision-making’ to a qualified human. Not one single existing AI system that has medical regulatory approval has yet claimed to be a ‘decision-maker’, and I sincerely doubt that one ever will, unless the decisions being made are minor and unlikely to be life-critical. This is because it is impossible for an AI system to ever be 100% accurate in solving a medical diagnostic question, because, as I have previously discussed, medicine in part still remains an art which can never be fully quantified or solved. There will always be an outlier, always be a niche case, always be confounding factors. And for that reason alone, we will always need some form of human oversight.

Reason 3. Productivity gains will drive demand

“If you build it, they will come” is the often misquoted saying from the movie Field of Dreams (or Wayne’s World 2, depending on your generation). If we build systems that massively improve radiology workflow and diagnostic turnaround, we will almost certainly see a massive increase in demand for medical imaging.

I’ve seen this with my own eyes — when I was a trainee, our department started a new initiative to try and reduce waiting times for ultrasound lists. We opened up an evening list with three or four extra slots for urgent walk-in patients or those that had been waiting more than 3 weeks. At first, this worked out nicely, with one trainee being assigned per day to this extra list. It only took an hour maximum after all. Fairly soon however, we started noticing requests coming in saying ‘for the extra list please’, and before we knew it we had to start opening up extra-extra lists, and extra-extra-extra lists, which in turn just became the new normal. My point here is that in radiology, if you offer a doctor a slot to scan a patient, they will find a patient to fill that slot!

As AI becomes the new normal in radiology, as scan times and waiting lists reduce, and as radiology reports become more accurate and useful, we will continue to see an increase in demand for our services. Add to this the ever increasing population growing in age and complexity, it is to me 100% inevitable that demand increases, and probably the major reason why I remain bullish on radiology as a career choice.

We will need to train more radiologists to combat the tidal wave of imaging being requested and data being produced, and may even consider dual or triple accreditation in other data-producing specialities such as pathology and genomics. ‘Radiologists’ may not even be called radiologists in the far future — at least that’s one theory I heard talked about at RSNA last year, but that doesn’t negate the fact that someone human will still be in control of the flow of data.

What will radiologist’s be doing then?

The radiologists of the next few decades will be increasingly freed from the mundane tasks of the past, and lavished with gorgeous pre-filled reports to verify, and funky analytics tools on which to pour over oceans of fascinating ‘radiomic’ data. It won’t quite be like Minority Report, but if you want to imagine yourself as Tom Cruise swiping and gesturing away at a screen of futuristic malleable real-time data, then go right ahead.

Where radiology artificial intelligence is heading towards is digital augmentation of radiologists, to the point at which their job becomes to monitor and assess machine outputs, rather than manually go through every possible mundane finding as they do now. Personally, I welcome this with open arms — I have wasted far too much of my working life measuring lymph nodes on multiple CT scans or counting vertebrae to report the level of a metastasis. I would much rather check a system has measured the correct lymph nodes and identified all the vertebrae required, and sign off on the findings. Radiologists are going to be transformed from ‘lumpologists’ with crude tools, to ‘data wranglers’ dealing with ever more sophisticated quantified outputs.

Radiologists will also be empowered to become more ‘doctor’ than ever before, with productivity gains allowing more time communicating results to both clinicians and patients. I can certainly envisage radiologists as data communicators, both directly to clinical teams on their rounds and tumour boards, and even direct-to-patient information-giving. The profession at the moment is only harmed by too much hiding away in dark rooms and, if anything, artificial intelligence has the capability of bringing radiologists back out into the light. That’s where it’s true power lies.

If you are as excited as I am about the future of radiology artificial intelligence, and want to discuss these ideas, please do get in touch. I’m on Twitter @drhughharvey.

Bio: Hugh Harvey is a board certified radiologist and clinical academic, trained in the NHS and Europe’s leading cancer research institute, the ICR, where he was twice awarded Science Writer of the Year. He has worked at Babylon Health, heading up the regulatory affairs team, gaining world-first CE marking for an AI-supported triage service, and is now a consultant radiologist, Royal College of Radiologists informatics committee member, and advisor to AI start-up companies, including Algomedica and Kheiron Medical.

Original. Reposted with permission.

Related: