||

I’m not talking about how to reproduce the miracle of Cana, I’m talking about how to edit strings! If you have the string WATER, on screen in a text editor, and want to change this into WINE, what could you do?

| |You could delete the entire word WATER, then type in each of the characters for the new word WINE. That would take nine operations (if we count each letter deletion as one operation, and each typed letter as one operation). Can we do better? Well, yes, both words contain a W and an E. We could delete ATR (three operations), then insert IN (two operations) for a total of five operations. Can we do better? Using just insertions and deletions, no, but if we’re allowed to perform substitutions (replacing one letter for another), we can reduce the number of steps to three:- Substitution: A->I WATER -> WITER- Substitution: T->N WITER -> WINER- Deletion: R WINER -> WINE|

|You could delete the entire word WATER, then type in each of the characters for the new word WINE. That would take nine operations (if we count each letter deletion as one operation, and each typed letter as one operation). Can we do better? Well, yes, both words contain a W and an E. We could delete ATR (three operations), then insert IN (two operations) for a total of five operations. Can we do better? Using just insertions and deletions, no, but if we’re allowed to perform substitutions (replacing one letter for another), we can reduce the number of steps to three:- Substitution: A->I WATER -> WITER- Substitution: T->N WITER -> WINER- Deletion: R WINER -> WINE|

Computer science calls the number of operations needed to change from one string to another as the Edit Distance. It’s also called the Levenshtein distance after the Soviet mathematician Vladimir Levenshtein, who studied this in 1965.

As we’ll see later, there are lots of uses for this distance. Strings (words) that are ‘close’ to each other have small edit distances. It’s easy to see how this could be useful for things like spell checkers and fuzzy name matching.

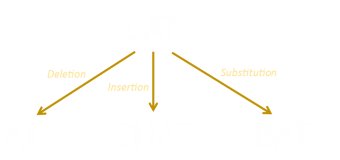

The Levenshtein edit distance between two strings is the minimum number of operations needed to convert one string into another using the three operations: Insertion, Deletion, Substitution. Normally each of these operations is given the same symmetrical cost of one unit, but there is a common variant where the substitution operation is given a cost of two units (essentially making it the same price as a deletion, followed by an insertion).

| |There are plenty of ways to edit one string and turn it into another, and each of these will have an edit distance, but how do we find and calculate the minimum distance?Let’s start with a simpler situation and work our way up to it.|

|There are plenty of ways to edit one string and turn it into another, and each of these will have an edit distance, but how do we find and calculate the minimum distance?Let’s start with a simpler situation and work our way up to it.|

Let’s start with a simpler situation and work our way up to it.

Hamming Distance

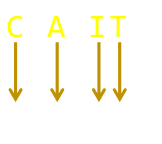

If the strings are the same length, and we don’t use any insertions and deletions, just substitutions, this edit distance is called the Hamming Distance.

Let’s look about how to change CHARITY into THERAPY.

| |This change can be done in four substitutions. An edit distance that only requires substitutions is also called a Hamming Distance. I’ve written about some of applications of this to error correction.For obvious reasons, for a string of length n, the maximum Hamming distance is n.|

|This change can be done in four substitutions. An edit distance that only requires substitutions is also called a Hamming Distance. I’ve written about some of applications of this to error correction.For obvious reasons, for a string of length n, the maximum Hamming distance is n.|

For obvious reasons, for a string of length n, the maximum Hamming distance is n.

Levenshtein Distance

| |If the two strings we wish to covert are the same length then the Levenshtein Distance can’t be greater than the Hamming Distance, though it can be less. As an example, the strings THERE and ETHER, have a Hamming Distance of five; requiring the change of every character, but a Levenshtein Distance of just two; deleting, then adding an E.If the strings are of different lengths, then the Levenshtein Distance has be be at least as long as the difference in their lengths.|

|If the two strings we wish to covert are the same length then the Levenshtein Distance can’t be greater than the Hamming Distance, though it can be less. As an example, the strings THERE and ETHER, have a Hamming Distance of five; requiring the change of every character, but a Levenshtein Distance of just two; deleting, then adding an E.If the strings are of different lengths, then the Levenshtein Distance has be be at least as long as the difference in their lengths.|

If the strings are of different lengths, then the Levenshtein Distance has be be at least as long as the difference in their lengths.

Recursion?

| |The simplest way to think about calculating the edit distance is with recursion. We can break down the problem to a smaller problem, and a smaller problem until we get to a base case that is trivial to solve, then flow back up again.|

|The simplest way to think about calculating the edit distance is with recursion. We can break down the problem to a smaller problem, and a smaller problem until we get to a base case that is trivial to solve, then flow back up again.|

The base case is pretty easy. If either one of the strings is empty, then the edit distance is just the length of the other string (insertion of each of the characters). Upstream, we don’t know the cheapest way to convert from one string to another (does it involve adding, removing, or changing a character), so we can evaluate all three possibilities and take the minimum found.

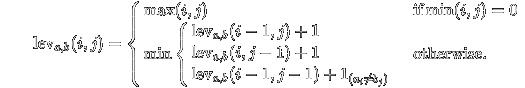

Let D[i,j] be the edit distance for two string of length i and j.

There are four ways we could get to this point:

-

From D[i-1,j-1] from a substitution (edit distance increases by one).

-

From D[i-1,j-1] from a match of character i-1 and j-1 (no change in edit distance).

-

From D[i-1,j] from a deletion (edit distance increases by one).

-

From D[i,j-1] from an insertion (edit distance increases by one).

(The first two are merged as a gimmie; the chars either match, or they do not). So, here’s the blueprint for the complete algorithm. It’s simple and elegant (but as we will shortly see, it’s totally impractical).

At each stage, we take the minimum possible edit distance of any of the three possible pre-fixes that could have brought us to this state, and it’s turtles all the way down until we hit the base case of when one of the strings is zero, then, at that point, it’s the length of the non-zero string.

Here’s the algorithm in pseudo code:

Function LD(x,y)

This works great, but suffers from a classic problem that many recursive algorithms do (see this article on ways to generate Fibonacci Numbers). Each call to the function fans out and makes lots of other calls to the same function.

If we instrumented this function and counted each time it’s called you can see just how the problem grows. We can add a couple of lines of instrumentation to illustrate:

Global N,M

Calling with LD(“cat”,”dog”), and we can see the LD function gets called 94 times (N=94), but what makes it worse is that the same sub problems are repeatedly solved over and over again. In the above case, M=13 so in calculating LD(“cat”,”dog”), the same intermediate function LD(“ca”,”do”) is determined 13 times (12 times redundantly, and each of these calls requires 19 sub calls!) It gets worse in a hurry.

To calculate the edit distance between “superman” and “superwoman” requires 1,884,697 calls to the LD function. In this case the function LD(“supe”,”supe”) is redundantly called 1,533 times.

This inefficiency can be partially addressed with a memoization technique. We can remember any previously calculated value in a cache, and store this. Each time we are asked to calculate the value of a particular pair of i,j we can look-up to see if we’ve already calculated it. If so, use that value (so we don’t have to drill down again). Here’s some pseudo code for how this could be implemented.

Function LD(x,y)

This memoization technique is sometimes called a top-down dynamic programming approach. An alternative is a bottom-up dynamic programming solution, and we can find a solution without the recursive overhead.

Wagner–Fischer algorithm

Starting with empty strings, the Wagner-Fischer algorithm builds up a matrix of the edit distances between ever increasing pre-fixes of the two words (at each point keeping track of the most efficient way to get to that state), until the entire matrix is filled. It does this in a way analogous to a flood-fill.

The Wagner–Fischer algorithm computes edit distance based on the observation that if we create a matrix to hold the edit distances between all prefixes of the first string and all prefixes of the second, then we can compute the values of longer prefixes from these, if we traverse the matrix in increasing order of length.

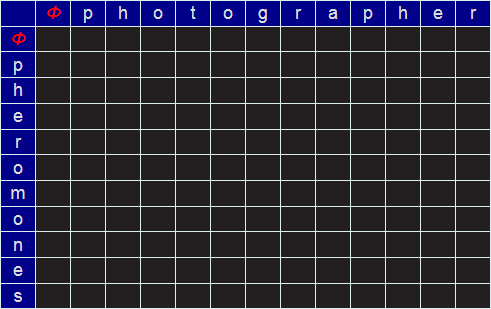

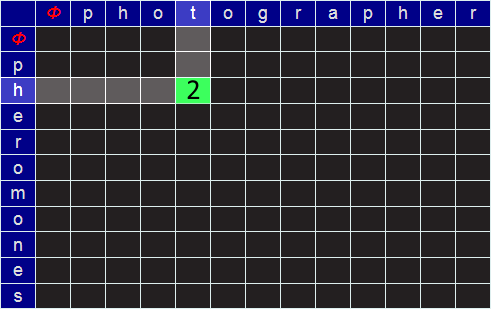

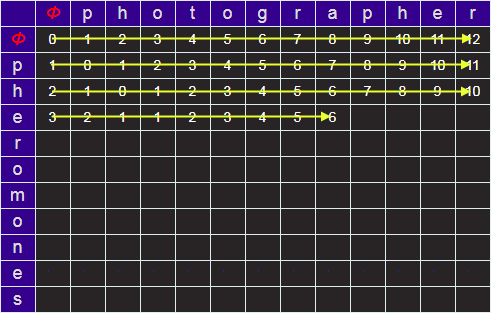

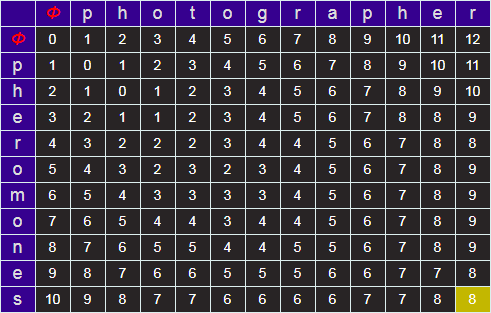

Let’s look at the example of how to change PHOTOGRAPHER to PHEROMONES (the edit distance of which is eight).

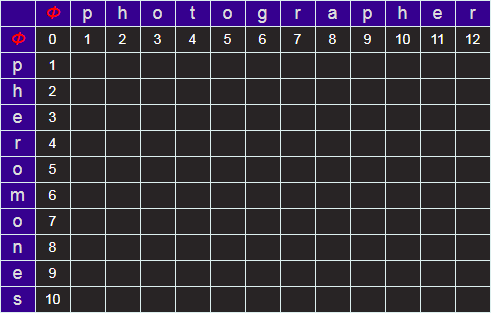

We start by creating an empty matrix of size LEN(“PHOTOGRAPHER”)+1 by LEN(“PHEROMONES”)+1.

We require the extra row and column to describe the NULL string (no letters). I’ll refer to this empty string by the Greek letter Φ. We’ll label this matrix, on the outside edge, for reference, with of the characters of the words. At every square on the grid will be the minimum edit distance to convert from the prefixes identified at the edges.

For example, in the grid below, the value placed in the green cell would be the minimum edit distance between the (word) prefixes PH and PHOT (which, I hope you can see, in this simple example is 2; we can get there be deleting the last two characters). But more generically, how do we calculate the value to place in an arbitrary cell?

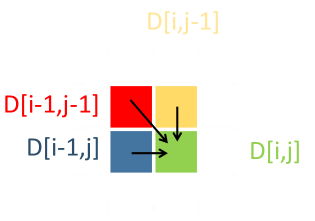

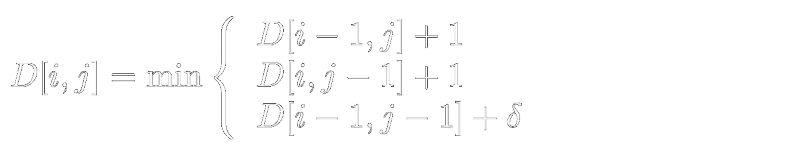

| For an arbitrary cell D[i,j], representing the prefix of each of these strings up to these lengths, there are three ways to get there, from three previous prefixes with their edit distances: D[i-1,j], D[i,j-1], and D[i-1,j-1]; Insertion, deletion and (potential) substitution. To preserve the minimum edit distance, we propagate forward the minimum edit distance. If we have to use the path D[i-1,j] or D[i,j-1], we add +1 to the edit distance of these respective values, representing the unit cost of inserting/deleting a character from the last position. If we use D[i-1,j-1] the cost is either +1 (if the characters at i and j are different; substitution), or zero if that pair of characters is the same. |  |

To preserve the minimum edit distance, we propagate forward the minimum edit distance. If we have to use the path D[i-1,j] or D[i,j-1], we add +1 to the edit distance of these respective values, representing the unit cost of inserting/deleting a character from the last position. If we use D[i-1,j-1] the cost is either +1 (if the characters at i and j are different; substitution), or zero if that pair of characters is the same.

(Where δ is either 1 or 0, depending on if the symbols at i,j are the different or the same).

Next we can fill in the row and column for corresponding to edit distances from Φ (the edit distances from null strings, which are simply the lengths of the prefixes).

Starting at the top left, we can iterate over the grid, calculating the minimum edit distance by comparing the three cells above, left, and diagonal from the required cell. When we get to the lower right, the answer for the minimum edit distance for the two strings will be in the bottom right cell.

Note - If you need to implement this algorithm, and memory is a constraint, there’s no reason why you need to keep track of the entire matrix in memory. As each wave front only needs the current, and previous, rows to advance; these are the only ones needed. Also, because of the symmetry of edit distances, the LD(A,B)==LD(B,A) you can transpose the matrix to only have to store the shorter of two rows (You can do this, simply, by swapping to the two strings, but analogous to this is to perform the scan vertically downwards, then advancing to the right, instead of horizontally and down).

Try it out

You can generate Wagner-Fisher matrices using the tool below.

The minimum edit distance is shown in the lower right corner (shaded yellow).

By default, the substitution cost is one unit (same as insertion and deletion), but you can optionally change this to two.

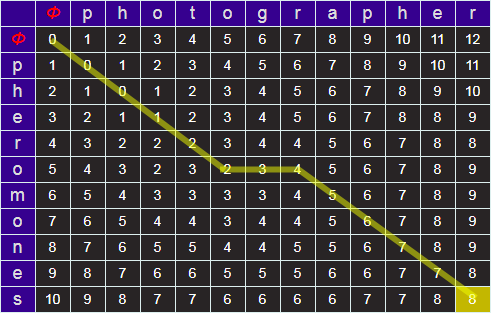

Backtracking The algorithm above provides an excellent way of calculating, efficiently, the minimum edit distance between two strings. What do we do if we actually want to know what the steps of the process are?

All this information, fortunately, is encoded in the matrix. For every cell, it’s possible to work out whence we came (which of the three possible upstream cells one has come from). It’s possible to back track this from the lower right back up to the top left. (Note - It’s very possible there may be more than one optimal path).

Above is a back track for our example.

Applications

An obvious application of Levenshtein distances is in spell checkers to suggest alternate words based on how ‘close’ they are to the entered bad word.

The algorithm can also be used at a word level too, to help identify potential duplicate entries. Many years ago I had a task of de-duplicating many thousands of hotel names in a database that was formed from the merging of multiple sources. Not only were there spelling errors, but there were multiple canonical variants of the hotel names. Applying a Levenshtein like algorithm at a word level allows identification of potential duplicates such as:

London Heathrow Hilton Hotel

Other Variants

There is no reason why the weights of the scores for Insertions, Deletions, and Substitutions need to be the same. Different “edit distance” results can obtained by modifying their relative weights.

Another variant, called the Damerau-Levenshtein distance, in addition to scoring the insertions, deletions, and substitutions, also scores single character transpositions (switching of two adjacent characters, which is a common error). It represents the smallest number of any of these moves to change from one string to another.

In his paper, Damerau estimated the 80% of human transcription errors can be classified as one of these four things.

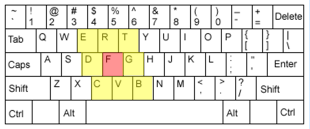

| |There’s no reason why non-matching substitutions have to have the same penalty; any pair of characters can be given distinct weights. For instance, a common type error is Sloppy Typing, in which a fat finger misses a key and hits one of the nearest neighbours. Similarly, different weights can be applied to similar sounding letters or pairs of letters to help guide a spell check, heuristically, in finding common mistakes.|

|There’s no reason why non-matching substitutions have to have the same penalty; any pair of characters can be given distinct weights. For instance, a common type error is Sloppy Typing, in which a fat finger misses a key and hits one of the nearest neighbours. Similarly, different weights can be applied to similar sounding letters or pairs of letters to help guide a spell check, heuristically, in finding common mistakes.|

Other Applications

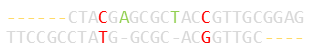

Modified versions of this algorithm have fascinating use in computational biology. For more information read about the Smith-Waterman algorithm, and the Needleman-Wunsch algorithm.

When looking at fragments and strings of DNA sequences, it’s useful to find areas that overlap, or have very common subsections (looking for important features, determining function, or possible evolution paths, or even detecting mutations). In these applications, we don’t care about, essentially, un-bounded gaps or errors at either end of a string, just the overlaps with minimal differences.

You can find a complete list of all the articles here. Click here to receive email alerts on new articles.

Click here to receive email alerts on new articles.