||

This article is related to the problem of how to stack pancakes perfectly. More specifically, it is related to how to make a perfect stack of pancakes using just a spatula, and an optimal number of flip operations (as we will see later, these are called “prefix reversals”).

The origin of this problem is an article appearing in American Mathematics Monthly, by Jacob Goodman in 1975. Here’s the introduction:

The chef in our place is sloppy, and when he prepares a stack of pancakes they come out all different sizes. Therefore, when I deliver them to a customer, on the way to the table, I rearrange them (so that the smallest winds up on top, and so on, down to the largest at the bottom), by grabbing several from the top and flipping them over, repeating this (varying the number I flip) as many times as necessary. If there are n pancakes, what is the maximum number of flips that I will every have to use to rearrange them?

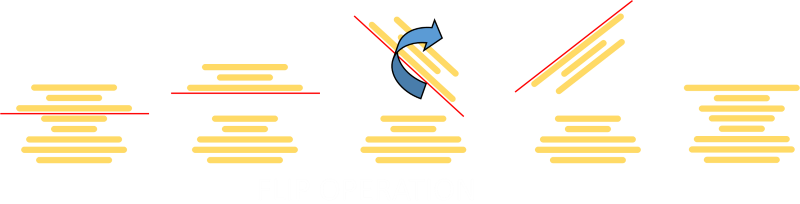

The only operation able to be performed on the stack is a prefix reversal. No additional storage can be used. A spatula is inserted at some location in the stack, those pancakes above lifted, flipped over, then placed back ontop of the stack.

Investigation

Before delving too deep, let’s look at a few trivial cases.

We can use numbers to describe the pancake diameters. We’ll call the smallest pancake 1, then next largest pancake 2, all the way to n. Numbers read top to bottom, so a perfect four stack would be 1-2-3-4.

For one pancake, there is nothing to do. By definition it’s already sorted.

The pancake number for one pancake is zero. PN(1) = 0.

For two pancakes, they are either the right way (1-2), or the wrong way (2-1). If they are the wrong way, flipping the stack once just inverts it. The maximum number of flips is just one. PN(2) = 1..

The first non-trivial arrangement is three pancakes. There are 3! ways that the chef could prepare the pancakes (3×2×1=6).

Here are all the possible cases:

| |If they were made in 1-2-3 order there is nothing to do!|

|

|If they were made in 1-2-3 order there is nothing to do!|

| |If they were made in 2-1-3 order they can be put into the correct order with just one flip. This can performed by inserting the spatula between the 1 and the 3.|

|

|If they were made in 2-1-3 order they can be put into the correct order with just one flip. This can performed by inserting the spatula between the 1 and the 3.|

| |If they were made in 3-1-2 order then it takes two flips to get them in order. The first flip inverts the stack, and this turns it into the 2-1-3 configuration seen above.|

|

|If they were made in 3-1-2 order then it takes two flips to get them in order. The first flip inverts the stack, and this turns it into the 2-1-3 configuration seen above.|

| |The 1-3-2 order is the most challenging initial configuration to get into order. It takes three flips.|

|

|The 1-3-2 order is the most challenging initial configuration to get into order. It takes three flips.|

| |The 2-3-1 configuration requires two flips (It’s an intermediate step seen as part of the configuration above .|

|

|The 2-3-1 configuration requires two flips (It’s an intermediate step seen as part of the configuration above .|

| |3-2-1 just requires the entire stack be inverted.|

| ||

|3-2-1 just requires the entire stack be inverted.|

| ||

The most number of flips that could possibly be needed is for the 1-3-2 case, and this is three flips.

The pancake number for three pancakes is three. PN(3) = 3.

Try it out yourself

Before going any further you might want to experiment with flipping a few pancakes yourself to learn some of the techniques. Below is a little interactive app to try it out.

The buttons on the top allow you to specify the number of pancakes in the stack. The pancakes will be made in random order. If you don’t like the configuration you can click the number button again, or tap the MAKE NEW STACK, to make a different initial configuration of pancakes.

Tap at the location in the stack you wish to insert the spatula, and click the FLIP button under the plate to flip the stack.

On the right, will be counted the number of moves taken. When solved, the best number of moves (shortest) to solve is displayed. If you want to replay the same stack again (in an attempt to beat you best score, or try an new tactic), clicking RESET will set the stack back to the same initial random state. To generate a whole new random state, use the MAKE NEW STACK button.

Finally, the SHOW NUMBERS option toggles display of numbers on the pancakes.

Experiment away and find some strategies!

Graph

Pretty soon, you may start to see that it’s possible to graph the solutions. From any state, there are only a finite number of possible other states that it is possible to get to. If there are n pancakes in a stack, then there are only n-1 places that we can insert the spatula (it’s pointless putting the spatula under just the top pancake of the stack as flipping this does not change the state!)

Let’s take a look at stacks of four pancakes. There are 4! possible configurations (states). We’ll make each state a node on a graph. With four pancakes, there are three possible states that we can transition to (corresponding to inserting the spatula in any of the three lower positions).

Links represent flipping. Flipping has a self-inverting property, and links can be traversed in either direction (and flipping twice with the spatula in the same location reverts the stack back).

In the graph below, in the centre, is desired finished state 1-2-3-4. If the chef had delivered the pancakes in this order there would be no work.

Surrounding this are the three possible states that it’s possible to get to the desired state in within one flip.

These are states 2-1-3-4, 3-2-1-4, 4-3-2-1. These are the only states that can be solved with one flip.

Next we can extend out from these nodes to find the states that are two flips away. All these new nodes represent states that are one flip away from the one flip states. Traversing the graph shows where to place the spatula, and the number of flips it takes to get between nodes.

Everything in this graph represents two or less flips to solve. To solve for the optimal solution for any configuration of initial pancakes, we can do this by finding the minimum path through the graph.

Adding the next level we can find all the nodes/states that take three flips to solve. There are 21 of the 24 states here.

Finally adding in the nodes that are, at most, four links away. The graph is starting to get a little busy!

The most number of flips that could possibly be needed for a stack of four is four flips. The minimum spanning tree from any node to the central node is not greater than four.

The pancake number for four pancakes is four. PN(4) = 4.

Pancake Numbers

||n|PN(n)1|0| |2|1| |3|3| |4|4| |5|5| |6|7| |7|8| |8|9| |9|10| |10|11| |11|13| |12|14| |13|15| |14|16| |15|17| |16|18| |17|19|

Pancake numbers have been studied for a while.

Finding the minimum number of flips is NP-hard (proved, in 2011, Laurent Bulteau, Guillaume Fertin, and Irena Rusu). As the number of possible stack arrangements is n! the space to search grows rapidly. Pancake numbers only up to stack sizes of 17 have been determined.

The current known numbers are shown on the left.

A formula to determine the exact number of minimum flips is not known, but upper limits are known.

A very simple solution is analogous to a selection sort algorithm. First, flip to bring the largest not yet sorted to the top of the stack, then take it down to the desired position with a second flip, then repeat as needed. The simplest pancake sorting algorithm requires at most 2n − 3 flips. This sets a naïve upper limit.

Better upper limits

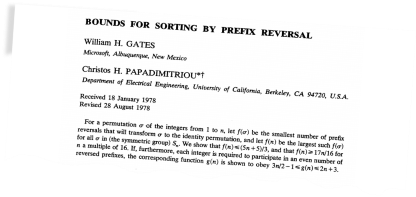

| |In 1979, a young Bill Gates (yes, that Bill Gates) and Christos Papadimitriou, wrote a paper proving a better upper bound of (5n+5)/3. You can read their paper here.|

|In 1979, a young Bill Gates (yes, that Bill Gates) and Christos Papadimitriou, wrote a paper proving a better upper bound of (5n+5)/3. You can read their paper here.|

Their record stood for almost 30 years until improved upon by Hall Sudborough in 2008, who proved the answer lies between 15n/14 and 18n/11 (approximately 1.07n and 1.64n, less than 2% improvement), but the exact value is not known.

Variants

In a variation called the burnt pancake problem, the bottom of each pancake in the pile is burnt, and the sort must be completed with the burnt side of every pancake down. It is a signed permutation.

Whilst this problem is typically described using pancake flipping, allegedly, Jacob Goodman, the author of the original article, thought of it whilst stacking folded towels between two tight shelves. As there was no additional storage space to stash towels in the swap, he needed to remove some towels, flip them over then slide them back onto the shelf.

You can find a complete list of all the articles here. Click here to receive email alerts on new articles.

Click here to receive email alerts on new articles.