||

| |When I was growing up, I loved puzzle books. The first puzzle book I picked up was Henry Ernest Dudeney’s 536 puzzles and curious problems. I still have my original copy of this book.In the words of Martin Gardner (another of my heroes), Henry was “England’s greatest maker of puzzles”. Praise indeed.The following puzzle has been attributed to Henry Ernest Dudeney. Along with optimal can dimensions it’s a very popular intro into calculus question taught in schools.|

|When I was growing up, I loved puzzle books. The first puzzle book I picked up was Henry Ernest Dudeney’s 536 puzzles and curious problems. I still have my original copy of this book.In the words of Martin Gardner (another of my heroes), Henry was “England’s greatest maker of puzzles”. Praise indeed.The following puzzle has been attributed to Henry Ernest Dudeney. Along with optimal can dimensions it’s a very popular intro into calculus question taught in schools.|

In the words of Martin Gardner (another of my heroes), Henry was “England’s greatest maker of puzzles”. Praise indeed.

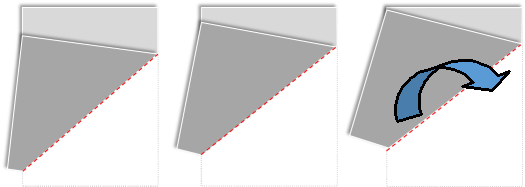

The puzzle is pretty simple: You are given a sheet of paper. You pick up one corner of the paper and fold it over so the corner touches somewhere on the opposite edge. The fold is flattened to a crease. The question is to determine the minimum possible crease length, and what point on the opposite side the crease should be made to.

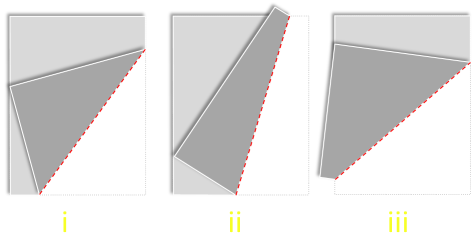

Thinking about it, there are three flavors of solution, shown below i, ii, and iii.

Another way to think of these cases is that, for case i, the crease connects the bottom of the paper to the edge of the paper. For case ii, the crease connects the top of the paper with the bottom of the paper. For case iii, the crease connects opposite sides of the paper.

Depending on the geometry of the paper, not all solutions are possible (for instance if the paper is not ‘tall’ and has an aspect ratio less than making it a square, then solution iii is not possible.

There’s also a couple of edge case configurations. The first is a 45° fold, and the second is folding directly in half but, with care, these should be handled as we deal with the generic cases.

Maybe you can intuit which case will result in the shortest length (Interestingly, if you search the web you’ll find out that most analyses only consider case i), but let’s look through each of the cases in order.

Case i

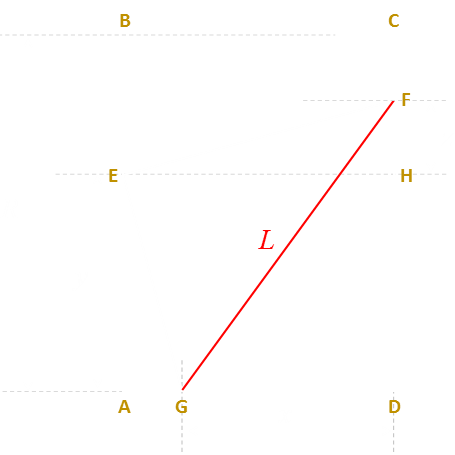

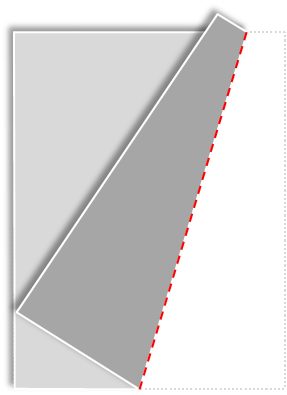

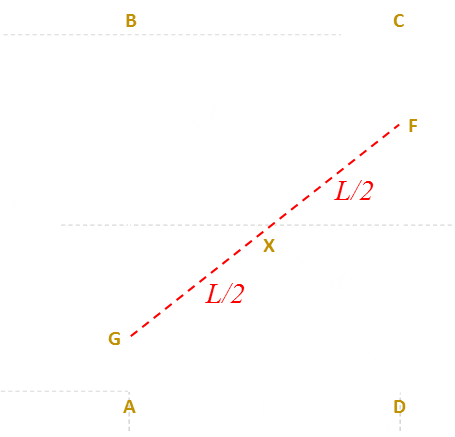

First let’s label some things:

| |- Let’s label the sheet of paper ABCD.- We’ll normalize the width of the paper to be 1 unit (AD=1).- The height of the paper, we’ll define as R units.- E is the point on the edge the paper folds to.- F and G describe the two ends of the crease.- L is the length of the crease.- x is the distance from corner folded, to the crease.- y is the distance up the paper the corner is folded to.- z is the distance from this point to the top of the crease.|

|- Let’s label the sheet of paper ABCD.- We’ll normalize the width of the paper to be 1 unit (AD=1).- The height of the paper, we’ll define as R units.- E is the point on the edge the paper folds to.- F and G describe the two ends of the crease.- L is the length of the crease.- x is the distance from corner folded, to the crease.- y is the distance up the paper the corner is folded to.- z is the distance from this point to the top of the crease.|

Looking at triangle AEG, and noting the EG is the same as DG (it’s just the paper folded over), we can apply Pythagoras:

There are similar triangles in the diagram, and we can use these to create another set of equations:

Rearranging this and substituting in eq 1 gives a result for z2

We now have the equations necessary to perform Pythagoras of the triangle to obtain the length of the crease L.

We have equations for all these variables in terms of x so it’s just a little algebra and simplification from this point onwards.

This is an equation to the length of the crease (squared), based on x. We can see it’s undefined when x ≤ 0.5 as this would make the solution imaginary. This makes sense as, to make the corner meet the other edge, we need to fold at least past halfway!

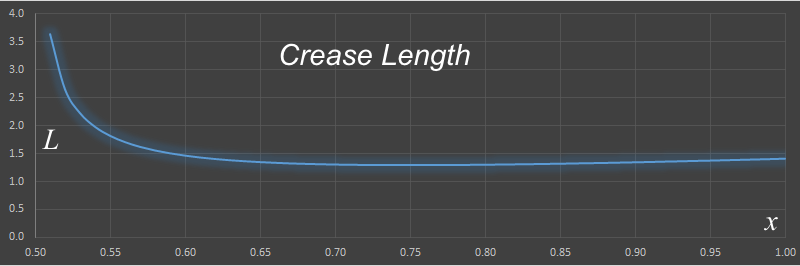

Here’s a graph of the crease length based on x.

You can see there is a minimum, and we could solve graphically, but let’s fire up the Calculus hounds and get an exact answer. We can differentiate the crease length with respect to x, and find out the turning points where this is zero. To simplify the Calculus, we can continue to work with L2.

We can see this is zero when the numerator is zero (and confirming the second differential is positive, indicating a minimum turning point). There are two answers. The first is the (trivial) answer when x=0 (when we don’t fold at all!), and the useful answer is when x=3/4.

For case i, the minimum length of crease is obtained when we fold the paper 3/4 of the way from the edge.

The length of the crease at this case is:

The other point of note is that, for case i, the minimum crease length is independent of the height of the paper.

Well, that’s not strictly true. If the paper is not tall (R is very small), then there reaches a point at which, when the 3/4 is folded over that the crease does not go all the way to the far edge.

This condition converts it to a case ii like problem.

There’s actually another case, if the aspect ratio gets even more extreme, and this is if there is not enough height to bend the 3/4 point over to the edge.

As will see below, for these cases, it’s pretty obvious that a shorter crease could be obtained by simply folding the paper in half.

The threshold at which case i stops applying is when the 3/4 crease passes through the opposite corner. As we know that x=3/4, we can use the equations above to above to calculate y+z and the threshold for this is when this is equal to R (the crease just touches the corner). This occurs when R ≤ 3/(2√2) ≈ 1.0607

Case ii

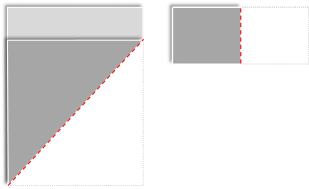

We can simplify case ii without having to break out any complex algebra or Calculus. For this case of solution, the crease connects the top edge of the paper with the bottom edge of the paper. The crease is a straight line, and the edges of the paper are parallel. The shortest distance between parallel lines is orthogonal to them.

The way to make this happen is to simply fold the paper in half! The minimum length for this case is simply R. It does not matter what the aspect ratio of the paper is for case ii, the shortest crease length will always be R.

For case ii, the minimum length of crease is obtained by folding the paper in half!

Case iii

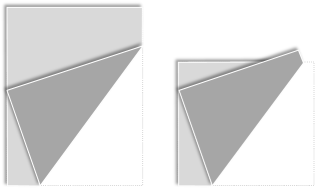

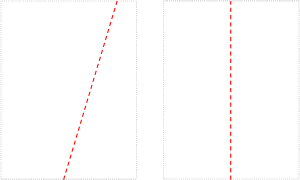

We can leverage the geometric principle above to simplify the solution to case iii too. Look closely at the diagrams below. As we move to the right, each diagram depicts the corner being fold up higher, and higher, on the edge.

The higher up the corner goes, the closer the crease line gets to being perpendicular to the edges. The closer the crease gets to 90° to the edges, the closer it gets to the minimum length. The way to minimize the length of the crease is to get the angle between the crease and the edge as close to perpendicular as possible. They way to achieve this is to fold the paper from corner to corner.

For case iii, the minimum length of crease is obtained by folding the paper from one corner to the other.

Here is what the crease looks like folded out. Because of symmetry you can see how the line connecting the corners and the crease cross at 90°

Labeling this:

From Pythagoras, the distance from one corner of paper to the other is simple:

Similar triangles ABD and XBG allow these ratios of edges:

Combining:

The crease length L is entirely dependant on the aspect ratio of the paper R, but is only valid for R ≥ 1 (where the paper is at least square. If the paper is less than square, case iii is not defined).

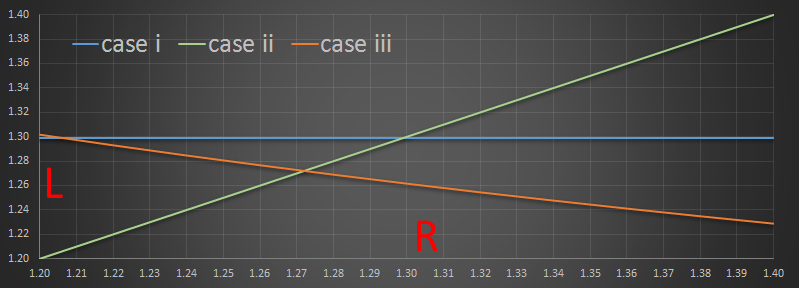

We now have formulae for the shortest length of crease for each of the cases i-iii

Here they are plotted on a graph. The y-axis shows the Length L and how this varies with the aspect ratio R of the paper.

If we zoom in closely we see something interesting.

We can see that case i is never the shortest possible crease! All those calculus text books are wrong (unless they were carefully worded to talk just about specifically case i).

Case i is never the shortest possible crease!

case ii (simply folding the paper in half) is the shortest crease possible up until some critical aspect ratio, and taller than this aspect ratio, case iii is the mechanism to to get the shortest crease. Let’s calculate this cross over point.

The cross over point occurs when the length of the crease for case iii is the case as case ii, which is simply the aspect ratio R. We can represent this as a quadratic in terms of R2.

We can solve this using the standard quadratic formula.

Something surprising falls out. This threshold is where R2 is the Golden Ratio!

Summary

-

Case i (that described in most calculus text books), is never the shortest crease.

-

If the aspect ratio of the paper squared is less than the Golden Ratio, the shortest crease is obtained by simply folding the paper in half.

-

If the aspect ratio of the paper squared is greater than the Golden ratio, the shortest crease is obtained by folding described by case iii.

-

If the aspect ratio squared is exactly the Golden ratio, there are two possible shortest creases, both the same length, corresponding the to case ii and case iii.

You can find a complete list of all the articles here. Click here to receive email alerts on new articles.

Click here to receive email alerts on new articles.