Linked Lists are incredibly useful programming data structures; they store both data and order information in a dynamic way. Before delving too deep, however, let’s first examine another staple data structure of programmers, arrays.

Arrays

Arrays are structures used to store collections similar objects (data) in a structured and ordered way. Each element in an array is identified by a unique index.

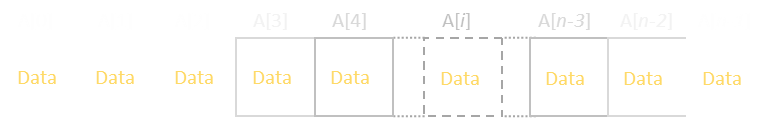

The example below shows a one-dimensional array of n elements.

An array is typically stored in a block of contiguous memory, and for this reason it is compact and efficient. Only the data is stored in an array. Because the elements of the array are of the same type (and size), the memory location for any element is simple to calculate (Take the index, multiply by the size of the data type, and add the off-set of the start of the array).

Arrays are some of the oldest and important structures in computer programming. They can be single dimensional, to represent lists and vectors, or multi-dimensional to store matrices and tables. They are efficient (requiring no additional storage overhead), and are fast to access.

They do, however, have a some disadvantages:

-

Their size needs to be determined beforehand, and memory allocated.

-

If the data to be stored is sparse (only a small number of indices contain data), they are wasteful.

-

If the values need to be accessed in a particular order, inserting and deleting elements can be time-consuming as, one-by-one, other elements may need to be shifted in a cascade.

Linked Lists

Linked lists solve all three of these problems (dynamic sizing, efficient storage of sparse data, and ease of insertion and deletion).

| |They do this by storing, not just the data, but also a pointer (sign-post) to the next element to be read. These pointers make a chain (a series of breadcrumbs to follow for how to navigate the data).The front of a linked list is called the Head. In essence, it’s just a pointer to the memory location that stores the first element of the list. In addition to the data, the linked list structure contains the pointer to the next element in the list, then this does to the next … until the last element is reached (called the Tail), and this is indicated by some sentinel value for the next pointer (typically a NULL, but depending how you implement could be zero, or a negative value).|

|They do this by storing, not just the data, but also a pointer (sign-post) to the next element to be read. These pointers make a chain (a series of breadcrumbs to follow for how to navigate the data).The front of a linked list is called the Head. In essence, it’s just a pointer to the memory location that stores the first element of the list. In addition to the data, the linked list structure contains the pointer to the next element in the list, then this does to the next … until the last element is reached (called the Tail), and this is indicated by some sentinel value for the next pointer (typically a NULL, but depending how you implement could be zero, or a negative value).|

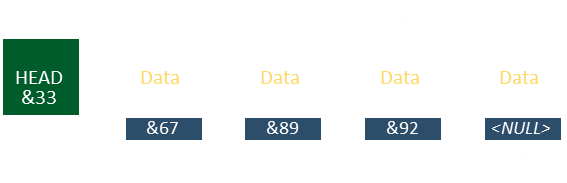

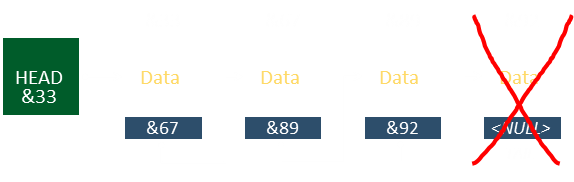

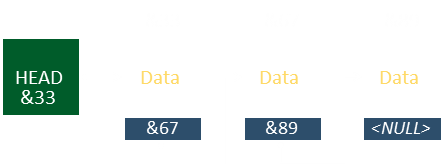

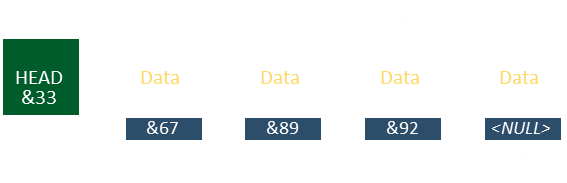

The front of a linked list is called the Head. In essence, it’s just a pointer to the memory location that stores the first element of the list. In addition to the data, the linked list structure contains the pointer to the next element in the list, then this does to the next … until the last element is reached (called the Tail), and this is indicated by some sentinel value for the next pointer (typically a NULL, but depending how you implement could be zero, or a negative value).

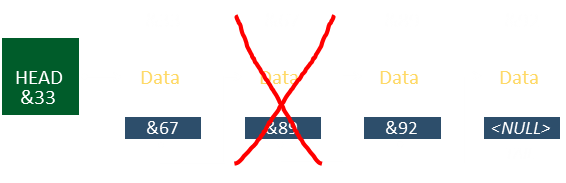

In the example below there are four elements stored in the list, and each element contains a pointer to the memory location that stores the next piece of data in the chain.

For all the advantages of linked lists, there are a couple of drawbacks:

-

Random access is not possible. To find a particular element, one has to start at the front, and walk sequentially through the list.

-

Additional memory is needed. In addition to the data, each element requires storage of a pointer which gives the address of the next element in the chain.

-

Potentially, linked lists can have poorer cache performance. With arrays, data is stored in a contiguous block, and memory is typically loaded and cached in chunks (especially when dealing with virtually memory, and loading blocks of data from slower media). For linked lists, the next element in a chain could be a pointer to anywhere in memory.

|

As with most things in life, therefore, there are compromises. As a software engineer you need to select the tool for the job that best fits your need. |

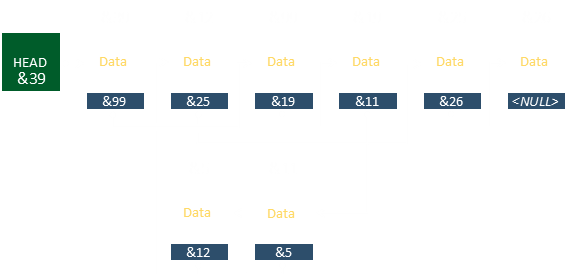

There is no particular reason why elements in a linked list will be stored in any particular order in memory. That’s entirely the point, the address of the next element is completely arbitrary.

The address of the head element is needed to access the start of a linked list. If the list is empty, then this will be NULL. Depending on the implementation of the list, the address of the current tail element may also be stored (which facilitates adding a new element at the end of the list). If the tail element address is not being kept, it can be found by starting at the head, and iterating through until a NULL is encountered as the pointer to the next element. Similarly, some implementations keep track of the number of elements in the list. It is up to the programmer to decide if the memory and processor overhead of keeping track of these items is a benefit compared to the need to have these values on-hand without calculation (or if some other process might be changing them without knowledge).

Insertion and deletion

Deleting an element from a link list needs to be performed with care to ensure that elements further downstream are not orphaned, or that loops do not occur (pointers referring back to previous elements so that iteration of the list never exits and gets stuck in an infinite loop).

| |The detection of loops in graphs/linked lists is a classic interview question, a good solution to which is Floyd’s Algorithm, also known at the “Tortoise and Hare” approach, and this is to move two pointers over the list at different speeds and see if they ever end up at the same location. |

|The detection of loops in graphs/linked lists is a classic interview question, a good solution to which is Floyd’s Algorithm, also known at the “Tortoise and Hare” approach, and this is to move two pointers over the list at different speeds and see if they ever end up at the same location. |

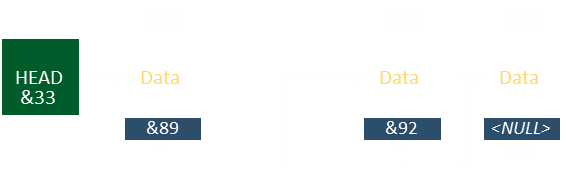

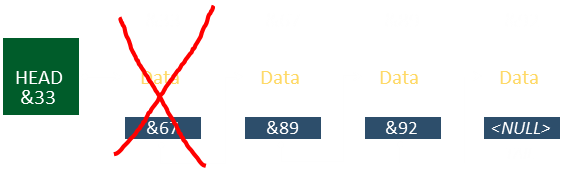

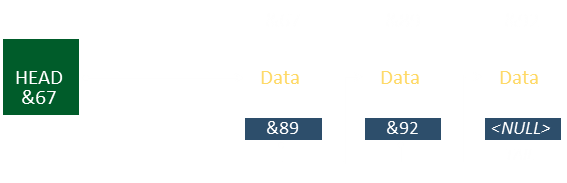

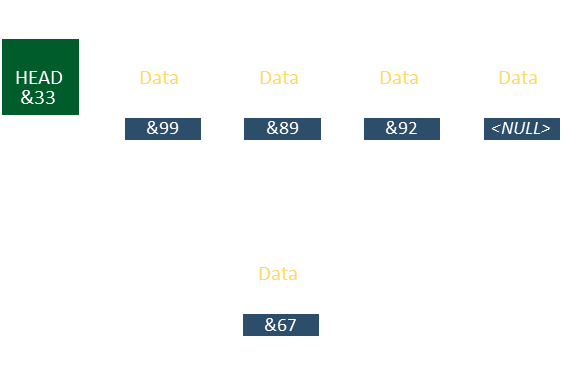

To delete an element from the middle:

Make sure the pointer for the upstream node correctly points to the address of the element downstream of the deleted element.

If the element to be deleted is the first element …

This will change the pointer of Head.

Finally, if the element to be deleted is the current tail …

Then the penultimate element should be updated with NULL as the next pointer.

(There’s also the test case where there is only one element currently in the array, and this is to be deleted. Correct defensive coding for the above cases should handle this case too).

Insertion

Similarly, inserting an element into an arbitrary location in a link list is simply a matter of updating the pointer of the referring element to the one being inserted, and making sure the new element points to the previously next element in the chain. (Again, taking care with the boundary cases of inserting at the tail and head).

Implementation

I’m, purposely, skipping over implementation details. There is, of course, memory management to have to worry about. Whilst we’re not pre-allocating a contiguous chunk of memory (as we would with an array), the dynamic nature of linked lists means that memory needs to be allocated when a new element is created, and when a node is deleted, this space should be freed up.

The next step up the sophistication chain is a structure called a doubly-linked list. This is pretty similar to a regular linked list with the extension that each node supports two pointers. One for the Next node, and one for the Previous node.

This allow traversals in both directions through the list!

As before, care needs to be taken with implementation to ensure the correct pointers are updated when insertions and deletions are made. With a doubly-linked list, the Previous pointer for the Head node will also a NULL, just the same way as the Next for the Tail node is.

An interesting way to think about a doubly linked list is like the next » and prev « buttons on a classic CD-Player, but to which the ordering of the play list has been randomized. For any track, all that needs stored, to enable this functionality, is what is the next track in either direction is.

With a doubly linked list, it’s easier to delete a node as we already know the address of the the element on either side. With a singly linked list, to delete a node, one has to start at the head and iterate through until the element to be deleted is found, keeping track of whence you came (There is no concept of previous in a singly linked list), so that this pointer can be updated.

Applications

Whilst sometimes cycles want to avoided, other times cycles in lists are required (and concept of what is a head or tail is arbitrary, other than the head pointer being used as the first entry into the structure). You can see how this data structure, with a loop, could be used to determine the next player in a game (where people might be able to arbitrarily leave and join at various positions), or to keep track of a deck of cards which get cycled through. Task Schedulers can also employ these structures to ensure every process gets an appropriately allocated execution.

You can find a complete list of all the articles here. Click here to receive email alerts on new articles.

Click here to receive email alerts on new articles.