· Read in 9 minutes · 1796 words · All posts in series ·

There is a dance—precisely choreographed and executed—that we perform throughout our lives. This is the dance formed by our movements. Our movements are our actions and the final outcome of our decision making processes. Single actions are built into reusable sequences, sequences are composed into complex routines, routines are arranged into elegant choreographies, and so the complexity of human action is realised. This synergy, the composition of actions into increasingly complex units, suggests the desirability of a modular and hierarchical approach to the selection and execution of actions. In both brain and machines, a synergistic strategy turns out to be one that is widely used.

A modular approach to action selection has a number of advantages: it simplifies the dimensionality of the action spaces over which we need to reason; it enables quick planning and execution of movements; it provides a simple mechanism that connects our plans and intentions to commands at the level of execution; and ultimately, it supports the rapid learning and generalisation that humans are capable of. Our exploration of brains and machines has thus far revealed that actions can be selected by associative learning (part 1) and that computation involves sparse representations (part 2). The actions involved have thus far been left vague, and this post explores the neuroscience and machine learning of actions and modular decision making.

Human action involves control of the motor system and the co-ordinated activation of a large number of muscles. Our muscles are combined in seemingly endless ways: we can make the coarse actions needed to hammer a nail into a wall, and follow this with the fine-grained actions needed to eat with chopsticks. Remaining within the framework of Marr’s levels-of-analysis, we are led to the computational problem of action selection: how is the brain able to learn, plan and rapidly execute complex movements? Or alternatively, how does the brain choose from the immense set of solutions for a motor task?

We develop and learn about actions and movements throughout our lives. Early human development from neonatal stages to that of a toddler is a time in which co-ordinated activations of groups of muscles are constantly explored, grouped into distinct patterns of movement, and added to our movement repertoire. These form our early movement primitives that, over the many years that follow from toddler to adult, we gradually shape and learn to exploit [1]. The distinct units of muscles and action that are formed are referred to as synergies.

The evidence for synergies in the brain are obtained using a variety of tools, including neural recordings taken simultaneously with muscle recordings using electromyography (EMG), functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), and the contrastive study of brain-damaged patients. Applying these tools in tasks related to reaching, grasping, maintaining posture, pain-based (nocifensive) reactions, and across a wide array of animal species, including humans, monkeys, cats and frogs, we are able to glean an implementation level understanding of synergistic action selection. Neural responses in the primary and supplementary motor areas are involved with muscle synergies, pre-supplementary movement areas code for a sequence of a movement as a whole, while the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) codes for progression in a multistep task and the boundaries of action sequences. Some of our experimental evidence includes [1][2][3]:

-

Direct evidence for synergistic movement in the monkey motor cortex, where single neural firing represents the activation of functional groups of muscles.

-

Direct evidence of synergies represented in the cortical networks controlling hand movements in humans [2].

-

In Rhesus macaques, micro-stimulation of the motor cortex corresponds to well-defined patterns of muscle activation.

-

Activation of populations of neurons in the cat motor cortex has been shown to initiate the activity of functionally distinct muscle synergies.

-

The brains of patients that are damaged following a stroke have been shown to have fewer synergies than those of a healthy human brain.

Our dance reaches its denouement as the muscle synergy hypothesisstating that the brain simplifies movement by composing useful patterns of movements as synergies, combining action patterns in a task-dependent way to attain a desired movement. We can differentiate between two types of synergies. Synchronous synergies employ groups of muscles that activate simultaneously, whereas* time-varying synergies* allow for delays between the activation of muscles. Synergies are part of a modular, hierarchical control strategy that is used by the brain to organise complex motor control variables and sensory feedback, a way to reduce the number of actions over which the brain must search and to allow for strong generalisation, and a way in which to quickly execute complex movements. But this remains a hypothesis since there are valid alternatives and doubts as to the validity of synergies [4]. Useful papers to explore this area of neuroscience include:

The complexity of human action has led us to the computational problem of how the brain learns and plans movements as rapidly as it does. One algorithmic solution uses a modular organisation of actions, whereby patterns of muscle activations are grouped into distinct units with task-specific temporal profiles, known as muscle synergies. These synergies are implemented in motor areas of the brain and co-ordinated through learning systems and representations, including those of associative learning and sparse coding. Modular organisation is a core tenet of computational science, and it is thus no surprise that such a strategy has also been used for learning in machines.

We now enter the theatre of machine learning with synergistic action, i.e. hierarchical reinforcement learning. On stage are machine learning systems that comprise three components: a model, a learning objective and an algorithm. Conveniently, we’ve already specified these components in our exploration of associative learning: parametric or non-parametric models for value functions, learning objectives that use Bellman error minimisation, and algorithms like Q-learning. The dance of movement and action is the principle performance.

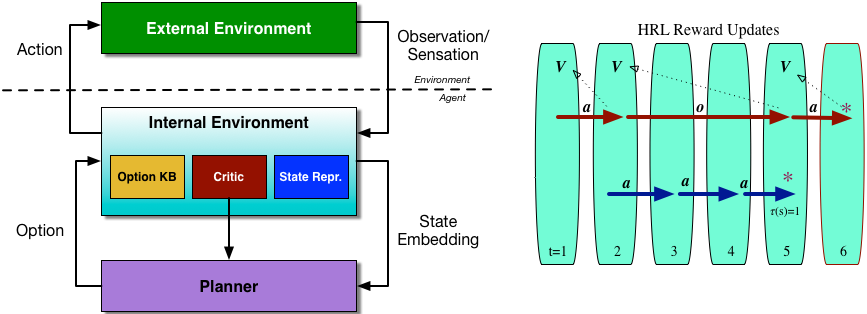

The actions in our setting have a hierarchy: the most basic, indivisible actions are referred to as primitive actions; a sequence of primitive actions is referred to as a macro-action. We also base our thinking on a very expressive perception-action loop that describes the flow of information in a reinforcement learning agent. The environment is split into an external and internal environment [5]. An agent receives observations s and takes primitive actions a in the external environment. The internal environment has three aspects:

(Left) Extended perception-action loop. (Right) Option execution.

-

State representation.Handles the processing of all input data, transforming it into a form that simplifies planning.

-

Critic. This is an important difference from the simplified perception-action loop used in part 1. Here, the source and nature of any reward signal is not assumed to be provided by an oracle in the external environment, but is part of the agent’s decision making system, and is responsible for the choice and computation of an appropriate internal reward signal. If external reward is available, it is passed on by the critic; this is also how intrinsic motivation enters the agent system.

-

Options knowledgebase. Allows for any temporally extended actions that have been chosen by the planning system to be translated into primitive actions and then executed in the external environment.

And because this is part of a hierarchical control strategy, this entire loop can be replicated within the planner. This modular structure allows us to recursively decompose a task into smaller sub-tasks. For every sub-task, we can specify a synergy of actions that allows us to achieve the sub-task; in reinforcement learning, synergies correspond to options. An option [6] is more general than a fixed sequence of primitive actions, it is an entire program  that computes the sequence of actions that will be taken, as well as a set of conditions

that computes the sequence of actions that will be taken, as well as a set of conditions  that tells the program when to terminate. The outputs of an option can be primitive actions or other options; primitive actions can be seen as special cases of options. When the option terminates, we can choose a new option and repeat this process.

that tells the program when to terminate. The outputs of an option can be primitive actions or other options; primitive actions can be seen as special cases of options. When the option terminates, we can choose a new option and repeat this process.

Like the state-action value function for primitive actions, we can define the state-option value function, which is the expected long-term discounted reward we assign to a state s when the first option we take is o, and thereafter all other options are taken according to a behaviour policy  .

.

With this definition we move from a Markov decision process to a semi-Markov decision process; we can modify our learning algorithm to account for modular structure and derive an options-based Q-learning algorithm [6]. This description has not mentioned how options are learned, and is an open problem [7][8]. There are also many alternatives to options such as the use of successor representations, the MAXQ algorithm, sequence chunking, and HQ-learning. Some papers that provide more detailed insight into options, temporal abstraction and hierarchical reinforcement learning are:

Action synergies in the brain are paralleled by macro-actions and options in machines. In both brains and machines, these tools enable fast learning, strong generalisation and flexible action. But most importantly, for we who seek a deeper understanding of the brain, and human and machine intelligence, this has illuminated the principles of modularity an abstraction—an invaluable principle of biological and computational learning.

Some References

Related