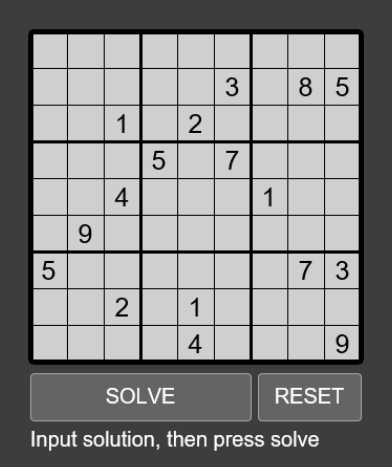

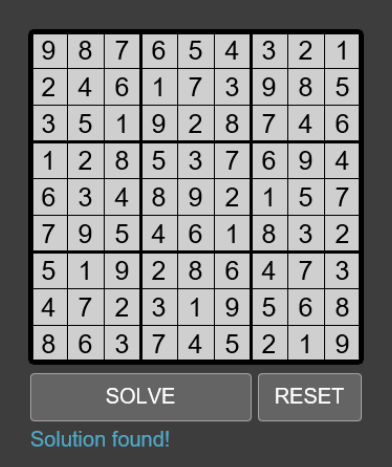

Click to input numbers into the blank grid. If there are no number collisions the solve button will be enabled. Note: If there are multiple solutions, only the first found is shown.

How it works

Writing a Soduko solver is something I’ve wanted to do for a while, but never got around to. This holiday break between Christmas and New Year, however, provided me with the perfect opportunity.

The basic process I use to solve puzzles is really simple; it’s nothing more complex than a brute-force recursive back-tracking algorithm. As with most programs, writing the code for the UI, to get the data in and out, and error checking, took twice as long as the code to calculate the solution!

Before starting, a referential check is performed on the input grid to ensure the puzzle is well formed (checking to see there are no digit clashes in any row, column, or box). If there are clashes, the offending cells are marked red, and the solve button is disabled.

When the solve button is pressed, the grid is scanned, looking for blank cells. If there are no blank cells left, then we have a solution!

When a blank cell is found, I create a vector array of all possible candidate digit values that could be used for this cell. This is made by starting off with all the digits 1–9, then removing candidates based on scanning the row, column, and grid, of this cell for collisions. I iterate through all the still valid candidates, trying each in return, and recursing into the problem looking for the next blank cell.

The success criteria is the filling of every blank square. Failure occurs if there is no possible candidate that could fill the blank square we’re working on. On failure, we reset the current cell to empty and backtrack to the previous level to try the next path. As stated above, in the interests of speed, I stop upon finding the first solution instead of enumerating them all, but it would be a simple change to carry on and find all solutions.

As with many recursive algorithms, there is a pleasing simplicity in the code. The recursion depth is not a concern as, at most, the depth will never exceed 81 levels (on a totally blank grid), though the tree can get wide. Another helpful thing in this implementation is that the changes to the puzzle matrix can be done in place rather than having to copy and duplicate the board as we recurse in. It’s very memory efficient.

Testing

“When you have eliminated the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth.”

If we wanted to be fiendish, knowing how the algorithm works, we can devise a ‘bastard’ puzzle that causes the most amount of stress, and create a worst-case puzzle for this code to solve. One such puzzle is below:

In this puzzle, there are not many given clues (in this case just 17), and the entire top row is blank. The final solution requires 987654321 in the top row, working directly against the algorithm and causing the maximum amount of vacillation. On my machine, this worst-case problem took a couple of dozen seconds (quite a contrast to the milliseconds for the average puzzle). However, a simple rotation of the input grid makes the problem trivial again, as does randomizing the order in which the blank squares are visited.

So, problems that are hard for people are pretty easy for computers to solve, and problems that are hard for computers rely on the puzzle generator having insight as to the algorithm the coder used to solve the problem.

Sudoku Trivia

-

There are 6,670,903,752,021,072,936,960 possible final sudoku grids (though only 5,472,730,538 if you remove reflections and rotations).

-

The minimal number of clues required to solve a unique puzzle has been shown to be 17.

-

The most clues needed to give a unique solution is believed to be 40 (if any of the clues is removed the result would be more than one solution).

-

The name “Sudoku” stems from two Japanese words: “su”, which means number and “doku”, which means single. Translated, it means “single numbers only”. However, despite the Japanese name, it was probably invented by an American, Howard Garns in 1979, who called in Number Place.

Other Game Solvers

If you like these kind of automated helpers, you might like some others I’ve written: