I have a sad story for you today.

Jason Collins tells it:

In The (Honest) Truth About Dishonesty, Dan Ariely describes an experiment to determine how much people cheat . . . The question then becomes how to reduce cheating. Ariely describes one idea: We took a group of 450 participants and split them into two groups. We asked half of them to try to recall the Ten Commandments and then tempted them to cheat on our matrix task. We asked the other half to try to recall ten books they had read in high school before setting them loose on the matrices and the opportunity to cheat. Among the group who recalled the ten books, we saw the typical widespread but moderate cheating. On the other hand, in the group that was asked to recall the Ten Commandments, we observed no cheating whatsoever.

Sounds pretty impressive! But these things all sound impressive when described at some distance from the data.

Anyway, Collins continues:

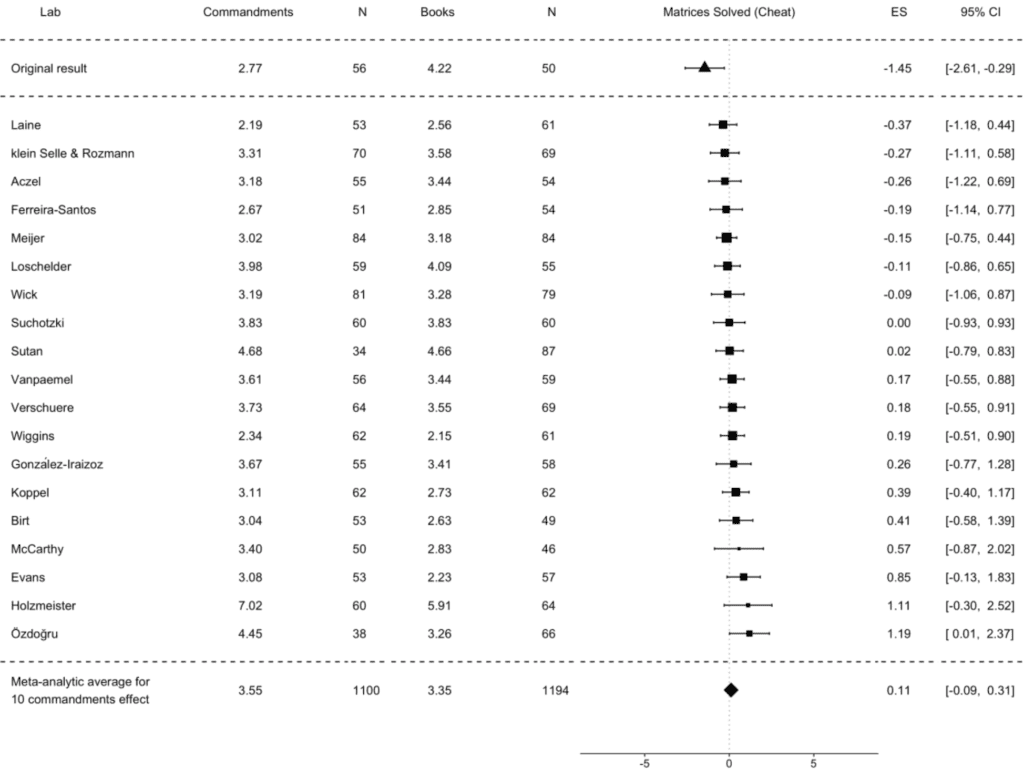

This experiment has now been subject to a multi-lab replication by Verschuere and friends. The abstract of the paper: . . . Mazar, Amir, and Ariely (2008; Experiment 1) gave participants an opportunity and incentive to cheat on a problem-solving task. Prior to that task, participants either recalled the 10 Commandments (a moral reminder) or recalled 10 books they had read in high school (a neutral task). Consistent with the self-concept maintenance theory . . . moral reminders reduced cheating. The Mazar et al. (2008) paper is among the most cited papers in deception research, but it has not been replicated directly. This Registered Replication Report describes the aggregated result of 25 direct replications (total n = 5786), all of which followed the same pre-registered protocol. . . .

And what happened? It’s in the graph above (from Verschuere et al., via Collins). The average estimated effect was tiny, it was not conventionally “statistically significant” (that is, the 95% interval included zero), and it “was numerically in the opposite direction of the original study.”

As is typically the case, I’m not gonna stand here and say I think the treatment had no effect. Rather, I’m guessing it has an effect which is sometimes positive and sometimes negative; it will depend on person and situation. There doesn’t seem to be any large and consistent effect, that’s for sure. Which maybe shouldn’t surprise us. After all, if the original finding was truly a surprise, then we should be able to return to our original state of mind, when we did not expect this very small intervention to have such a large and consistent effect.

I promised you a sad story. But, so far, this is just one more story of a hyped claim that didn’t stand up to the rigors of science. And I can’t hold it against the researchers that they hyped it: if the claim had held up, it would’ve been an interesting and perhaps important finding, well worth hyping.

No, the sad part comes next.

Collins reports:

Multi-lab experiments like this are fantastic. There’s little ambiguity about the result. That said, there is a response by Amir, Mazar and Ariely. Lots of fluff about context. No suggestion of “maybe there’s nothing here”.

You can read the response and judge for yourself. I think Collins’s report is accurate, and that’s what made me sad. These people care enough about this topic to conduct a study, write it up in a research article and then in a book—but they don’t seem to care enough to seriously entertain the possibility they were mistaken. It saddens me. Really, what’s the point of doing all this work if you’re not going to be open to learning?

(See this comment for further elaboration of these points.)

And there’s no need to think anything done in the first study was unethical at the time. Remember Clarke’s Law.

Another way of putting it is: Ariely’s book is called “The Honest Truth . . .” I assume Ariely was honest when writing this book; that is, he was expressing sincerely-held views. But honesty (and even transparency) are not enough. Honesty and transparency supply the conditions under which we can do good science, but we still need to perform good measurements and study consistent effects. The above-discussed study failed in part because of the old, old problem that they were using a between-person design to study within-person effects; see here and here. (See also this discussion from Thomas Lumley on a related issue.)

P.S. Collins links to the original article by Mazar, Amir, and Ariely. I guess that if I’d read it in 2008 when it appeared, I’d’ve believed all its claims too. A quick scan shows no obvious problems with the data or analyses. But there can be lots of forking paths and unwittingly opportunistic behavior in data processing and analysis; recall the 50 Shades of Gray paper (in which the researchers performed their own replication and learned that their original finding was not real) and its funhouse parody 64 Shades of Gray paper, whose authors appeared to take their data-driven hypothesizing all too seriously. The point is: it can look good, but don’t trust yourself; do the damn replication.P.P.S. This link also includes some discussions, including this from Scott Rick and George Loewenstein:

In our opinion, the main limitation of Mazar, Amir, and Ariely’s article is not in the perspective it presents but rather in what it leaves out. Although it is important to understand the psychology of rationalization, the other factor that Mazar, Amir, and Ariely recognize but then largely ignore—namely, the motivation to behave dishonestly—is arguably the more important side of the dishonesty equation. . . . A closer examination of many of the acts of dishonesty in the real world reveals a striking pattern: Many, if not most, appear to be motivated by the desire to avoid (or recoup) losses rather than the simple desire for gain. . . . The feeling of being in a hole not only originates from nonshareable unethical behavior but also can arise, more prosaically, from overly ambitious goals . . . Academia is a domain in which reference points are particularly likely to be defined in terms of the attainments of others. Academia is becoming increasingly competitive . . . With standards ratcheting upward, there is a kind of “arms race” in which academics at all levels must produce more to achieve the same career gains. . . . An unfortunate implication of hypermotivation is that as competition within a domain increases, dishonesty also tends to increase in response. Goodstein (1996) feared as much over a decade ago: . . . What had always previously been a purely intellectual competition has now become an intense competition for scarce resources. This change, which is permanent and irreversible, is likely to have an undesirable effect in the long run on ethical behavior among scientists. Instances of scientific fraud are almost sure to become more common.

Rick and Loewenstein were ahead of their time to be talking about all that, back in 2008. Also this:

The economist Andrei Shleifer (2004) explicitly argues against our perspective in an article titled “Does Competition Destroy Ethical Behavior?” Although he endorses the premise that competitive situations are more likely to elicit unethical behavior, and indeed offers several examples other than those provided here, he argues against a psychological perspective and instead attempts to show that “conduct described as unethical and blamed on ‘greed’ is sometimes a consequence of market competition” . . . Shleifer (2004) concludes optimistically, arguing that competition will lead to economic growth and that wealth tends to promote high ethical standards. . . .

Wait—Andrei Shleifer—wasn’t he involved in some scandal? Oh yeah:

During the early 1990s, Andrei Shleifer headed a Harvard project under the auspices of the Harvard Institute for International Development (HIID) that invested U.S. government funds in the development of Russia’s economy. Schleifer was also a direct advisor to Anatoly Chubais, then vice-premier of Russia . . . In 1997, the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) canceled most of its funding for the Harvard project after investigations showed that top HIID officials Andre Shleifer and Jonathan Hay had used their positions and insider information to profit from investments in the Russian securities markets. . . . In August 2005, Harvard University, Shleifer and the Department of Justice reached an agreement under which the university paid $26.5 million to settle the five-year-old lawsuit. Shleifer was also responsible for paying $2 million worth of damages, though he did not admit any wrongdoing.

In the above quote, Shleifer refers to “conduct described as unethical” and puts “greed” in scare quotes. No way Shleifer could’ve been motivated by greed, right? After all, he was already rich, and rich people are never greedy, or so I’ve heard.

Anyway, that last bit is off topic; still, it’s interesting to see all these connections. Cheating’s an interesting topic, even though (or especially because) it doesn’t seem that it can be be turned on and off using simple behavioral interventions.