The Game

Imagine two people are playing a, greatly simplified, poker game:

Each player makes a $1.00 wager (ante) to start the game.

Each player is then ‘dealt’ a number between 0.0 – 1.0 (continuous), to represent their ‘hand’. Players can see their own number, but not their opponent’s.

After examining their hand, the first player has the option to Fold, Check (stand), or Raise (Doubling the wager to $2.00).

The second player can either Call (if the first player raised), Check, or Fold.

If there is a showdown, the player with the highest number wins. Winner takes all.

What is each player’s optimal strategy?

What is each player’s optimal strategy?

First Level Thinking

Well, first of all, there are a couple of obvious things: Clearly, it’s never a good idea for the first player to fold! Ever! No matter how low their score there’s a chance they could win, and they’ve already paid the wager. If they fold, they are guaranteed to lose the $1.00. If they stay there’s a chance they could win.

Similarly, the second player should never fold if the first player did not raise.

There is no point in the second player bluffing, as there is not a second round of betting.

The first player, however, can bluff (and as we will see later, this is important).

It costs nothing extra for either player to Check.

Next, since the numbers are continuous, there can never be a tie. One player is bound to win.

If the first player has a ‘good’ hand then it’s in their interest to double the wager.

If the second player thinks they might have a better hand, it’s in their interest to accept the doubled wager; if they think they have a poor hand, then it is better for them to fold.

This last part is important to the first player: The second player will fold if they are holding a low hand when the first player raises. It’s, therefore, possible for the first player to bluff. If they have a poor hand, they can still double on the chance that the second player has a poor hand (and, otherwise would simple ‘check’ for free).

Bluffing is risky, but sometimes it is successful in buying the pot. Interestingly, it is with low quality hands that the first player should bluff (not medium quality). Why? Well, when a player bluffs they typically expect to lose if they are called (so it does not depend on quality; you can bluff with anything), but with a medium hand, quality matters, and so one is better off checking.

Next Level Thinking

The first player has to base their actions on the value of the card they hold and their understanding of how the second player will play. The first player has to assume the second player will play optimally (after all, if the second player doesn’t play optimally, it’s even better for the first player!) Based on this, the first player will act accordingly to maximize their chances.

Similarly, the second player has to base their decision on their card, and their understanding that the first player will play optimally.

Nash Equilibrium

For optimal play by both players we can describe the solution to this game as something that has reached a Nash Equilibrium. (Named after the late brilliant mathematician John Forbes Nash Jr who won the Nobel prize for some of his work). A Nash Equilibrium is a solution in which both players can gain no benefit from changing their strategy.

A very commonly quoted example of a Nash Equilibrium is The prisoner’s dilemma.

As the rules to this poker game are clear, and each player can determine their opponent’s optimal strategy, the optimal game can be reduced to a Nash Equilibrium. Even knowing what they know, neither will change how they play (because if they did, they would decrease their chances of winning).

In the end you simply have to adopt a strategy that minimizes the maximum regret you might feel.

In our poker example we are dealing with just two players, but Nash Equilibria can exist with any number of combatants.

A simple test to determine if a Nash Equilibrium exists is for all players to reveal their play strategy. If, knowing all this, no player elects to change their strategy, then a Nash Equilibrium is proven.

A simple test to determine if a Nash Equilibrium exists is for all players to reveal their play strategy. If, knowing all this, no player elects to change their strategy, then a Nash Equilibrium is proven.

von Neumann

What von Neumann and O. Morgenstern showed is that optimal play for the second player is based on a threshold value. If the first player raises, any hand dealt to the second player that is above this threshold value is Called. Any hand with a value below the threshold value is Folded. (As we will see below, the value of the threshold depends on the level of the raise). A very simple strategy.

The first player can also determine what the second player players optimal threshold is, and has the luxury of acting first. Based on their hand they can decide how to act. They have three options:

If they have a high hand, they will want to raise. If the second player folds, they’ve bought the pot. If the second player calls, they stand a good chance of winning a larger pot.

-

If they have a mediocre hand, they will simply check (no use risking a double).

-

If they have a very poor hand, they should bluff (what do they have to lose?) There’s a chance that this will cause the second player to fold (if their hand is below the threshold), that otherwise would have come to showdown with both players checking.

Player one has two thresholds. The first is what value, above which, they will raise. The second is, below which, they will bluff.

Bluffing is an essential part of player one’s strategy, and is needed to maximize the expected return to them. If they did not bluff at the low end, they are leaving money on the table. Even though player two knows that player one bluffs sometimes, a raise on a bluff is indistinguishable from a raise on a high hand, and if they call, they risk butting up against a high hand at an increased stake. What von Neumann showed is that the first player’s bluff threshold is at a level of indifference for the second player in that there is no advantage to calling on these. If the first players bluff threshold was artificially higher, there would be added incentive for the second player to call more often in the chance of catching the first player in a bluff.

Math

We can look at the results of von Neumann’s research, but more generically; instead of simply allowing doubling, the first player is allowed to raise the pot by an amount B dollars. So, in our example above: B=1. The initially ante is $1, and to double the bet is an additional $1 (B=1).

The threshold that the second player will call/fold, based on a raise value of B, is given by the following forumla:

Using our example of doubling down (B=1), this gives the solution that the second player should call, when raised, if they have a hand with value P2T > 4/10 (or 0.4), otherwise fold.

The formula for the first player’s threshold of when to raise with good hand is shown to be:

Again with using (B=1), we can see this equates to a hand value of P1TH > 7/10. Anything higher than this and it’s an automatic raise.

Finally, the formula for the first player’s threshold of when to bluff is:

With (B=1), this is for a hand with scores P1TL < 1/10. Any hand below this value, and it’s in the first player’s best interest to bluff and raise.

The advantage (value) to the first player is given by the the formula:

So with the a simple double option (B=1), then first player has a 10% advantage if both players play optimally.

Simple game with a single double down

In summary, if the raise option to the first player is a double down (B=1), then:

0.1 < P1 < 0.7 then Check, otherwise Double.

P2 > 0.4 then Call if raised, otherwise Fold. Check if checked to.

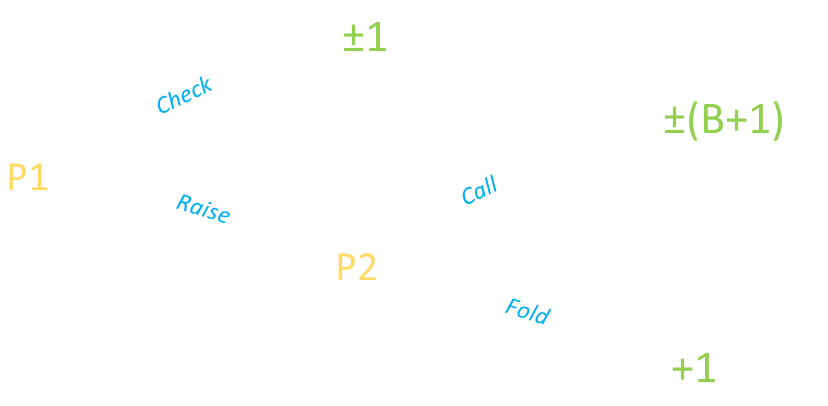

Game Decision Tree

Here is a tree showing the decision paths and potential pay-outs for the first player.

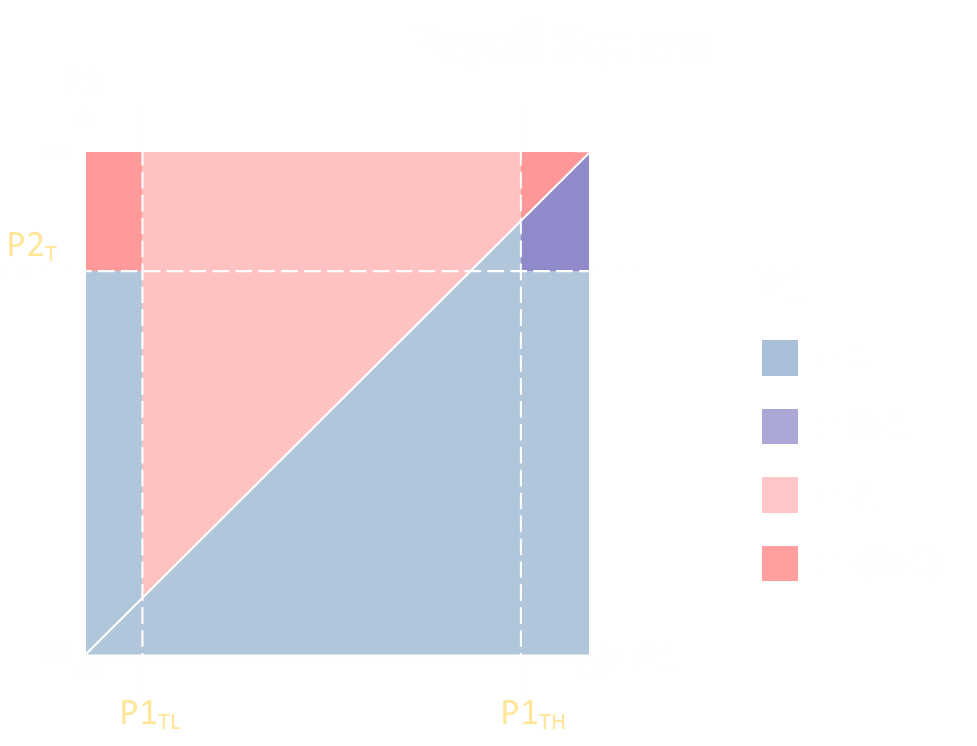

Graph

This solution is easier to visualize on a graph as a payoff square. On the x-axis is the first players hand [0.0–1.0], an on the y-axis is the second players hand [0.0–1.0]. Any coordinate inside this unit square depicts an unique pair of hands in the game. We can shade the square based on who wins, and what the resulting payoff will be.

The leading diagonal P1=P2 is the boundary about which, absent of anything else, bisects the square and determines the winner. However, there are additional regions to consider, and different payout scenarios.

The left vertical line depicts the threshold, below which, P1 bluffs. They will automatically win (buying the pot) in the lower part of the rectangle, up to the point that P2 will call, but above this will lose out (and lose the bigger wager). The right vertical line depicts the threshold, past which, P1 will raise. The victor of this showdown will win/lose a larger wager if the raise is called.

The horizontal line shows the threshold for P2.

You can see how bluffing is an essential part of P1’s strategy to maximize their return.

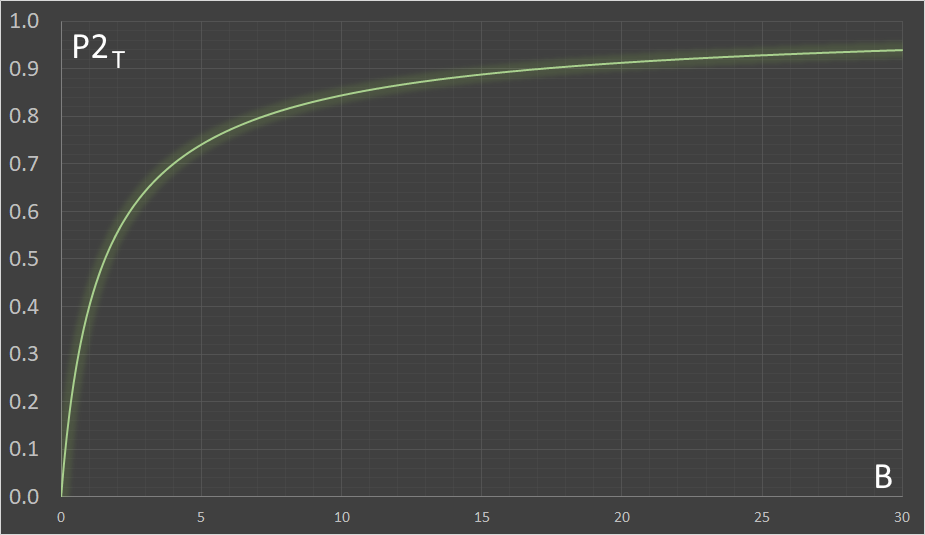

Charting

We can plot the formulas for the threshold values on charts. Here is a chart of how the second player’s threshold value changes as B increases.

You can see that, as the value of the potential raise increases, so does the second player’s threshold. If the first player raises a huge amount, the second player is only going to call if they have a really good hand. At the extreme limit, the second player will never call a raise. Why risk it?

At the other extreme, when B=0 (no raise), the second player will always call (duh!), it’s the same as a check.

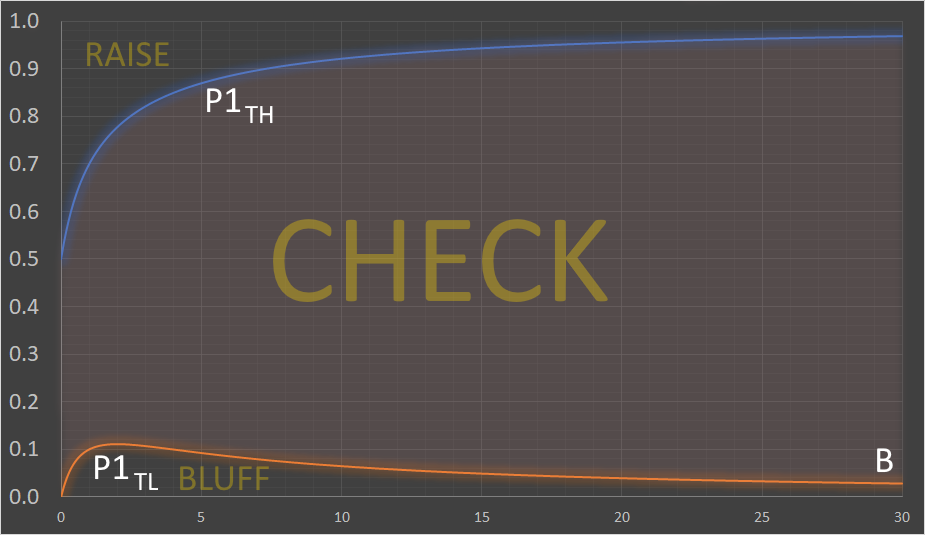

The graph for the first player’s strategy is even more interesting:

The region in the middle represents that hand values at which P1 just calls. The lower section curve is the threshold to bluff, and the higher curve the raise threshold.

Interestingly, the bluff curve initially rises to some maximum, then falls away (with increasing B, initially bluffing more aggressively, then slowing down). The bluff curve finally asymptotes to zero. If the potential raise value gets too high, it’s not worth the risk. Sure, you might buy the pot, but the downside of being called in the bluff is too steep. It’s a similar situation with the raise threshold, but this curve does not exhibit a turning point and is monotonic (increase in B always increases the threshold).

Again at B=0, it’s a 50% threshold, essentially a coin flip between a raise and a check, but since the raise is zero, even if it was a raise, it’s indifferent from essentially a wager at a different value.

If B gets too large, both players simple check!

Optimal Betting

We can use Calculus to determine the optimal bet size for P1 for playing the game.

Differentiating the value function with respect to B, and setting this to zero determines the turning points. This occurs when B=2. (We can see on the graph this corresponds to the maximum on the orange graph, but we can also confirm this by the fact that the second differential at the point B=2 is negative).

(Note - All of this assumes that the value for B is known in advance to both players and does not change. An additional dimension can be applied to the game in which the first player, upon seeing his hand determines the value of B based on the hand value. Analysis of this has been performed (see Donald J. Newman (1959) “A model for ‘real’ poker”). The summary of his strategy is that the first player bets more when the have a better chance of winning (or bluffing), and even though this telegraphs information to the second player that they have either a good hand or bad hand, in true Nash Equilibrium form, the second player cannot gain advantage in this as it is factored into the solution already and the values and thresholds that the first player uses. Even though the second player can think “I know what you’re doing”, they can’t leverage an advantage out of it).

Non-continuous Game

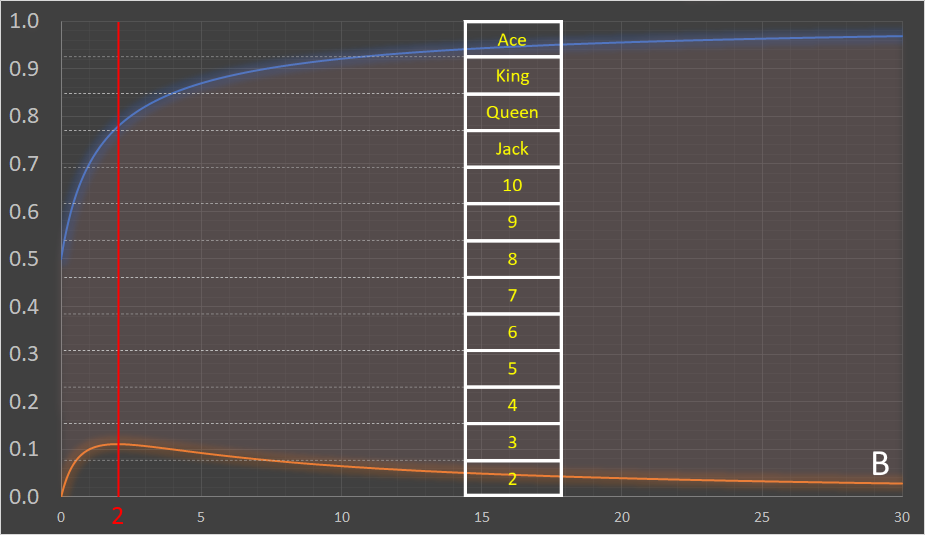

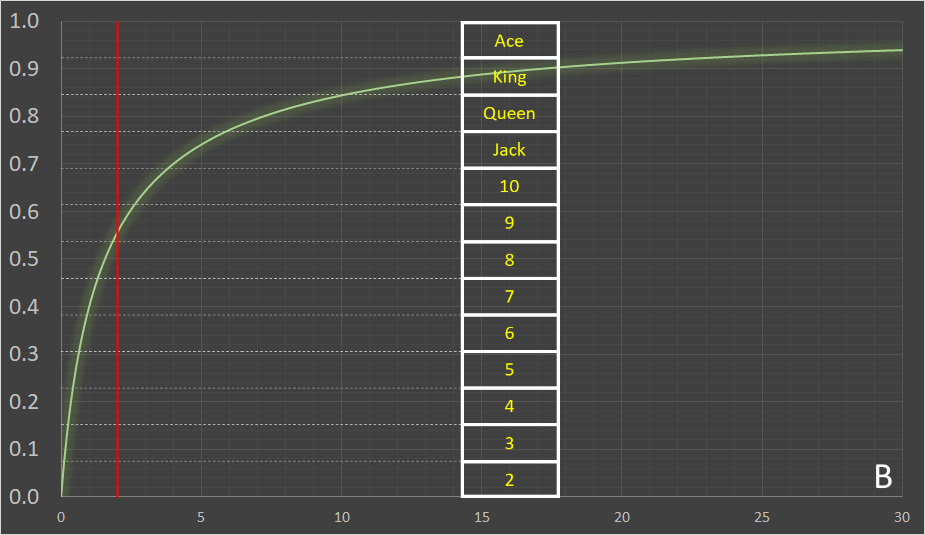

The above analysis was based on a continuous hand ranking, but a good first approximation can be made using this data to provide a strategy for the game of one card poker. In one card poker, each player is dealt a single hole card. The winner at showdown (asuming the second player does not fold) is the player with the highest ranked hand [Ace-Two].

It’s not quite the same, as a push (tie) is possible in one card poker, and the curve doesn’t naturally flow through the distinct card thresholds, but superimposing the 13 spaces for the cards over the curves gives a first approximation.

The red line is drawn for B=2 (pot-limit betting), as an example to see what the thresholds might be. The curves suggest a mixed strategy could work well. For player one, this is to raise on {Ace, King, Queen, Two}, otherwise check, but then to also raise (bluff) on a {Three} on a coin flip (as the curve passes approximately mid-way through this region).

The optimal strategy for the second player is to call the raise if holding {Ace, King, Queen, Jack, Ten} and also most of the time with a {Nine}, but not all the time.

The Price is Right

If you enjoyed this article, you might like reading about the optimal strategy if you ever get selected to be a contestant on the game show The Price is Right, and make it through the to the Showcase final and need to spin the big wheel.

In the final spin, the last player to go has nothing to lose and can spin either to win, or bust trying, but the first player to spin has to consider what the optimal stopping score would be.