By Angel Castellanos Gonzalez, Data Scientist

Introduction

Chatbots, (a.k.a. Conversational Agents, a.k.a. Dialog Systems, a.k.a. Virtual Assistants) are the new apps, they are omnipresent and everyone wants its own. Nevertheless, regardless of the different approaches followed to build chatbots, one feature is common to all of them: its building process is time-consuming and it is far from being straightforward.

Many applications and platforms aim to reduce the time-to-market of a chatbot app. Some even promise a “chatbot in 5 minutes”. Anyone with enough experience in chatbot development knows how far from the truth these claims are.

The sad truth: creating a chatbot is difficult, it involves knowledge in many AI-Hard tasks, such as Natural Language Understanding, Machine Comprehension, Inference, or Automatic Language Generation (in fact, solving these tasks is close to solving AI) and large human effort is required.

What we expect of a chatbot → and what we actually have

What we expect of a chatbot → and what we actually have

Defining a Chatbot

Chatbot definition is as varied as the addressed scenarios. Deploying a general-domain virtual assistant (e.g. Siri) entails very different challenges than building a conversational agent for elders or a customer-service chatbot for a bank. Anyhow, there is a series of steps that are common to any domain:

- Intent Definition: Natural Language and Human Communication are so diverse that they include a potentially infinite number of topics. However, to build a chatbot one has to narrow down the scenarios to be addressed (i.e., the intents to be covered). Sometimes, these intents are crystal clear (I want a chatbot to buy plane tickets), but many other times they have to be identified through a slow process of exploration, analysis and understanding of your data.Once defined, the chatbot must be able to automatically identify these intents in the upcoming user utterances. To that end, machine learning algorithms have to be trained and optimized to the defined intents and the specific chatbot scenario.

As one can imagine, each and every of these steps is time-consuming and it requires the involvement of domain and machine learning experts. A whole ecosystem of platforms and libraries exists to facilitate this process (Microsoft LUIS, Google’s Dialogflow, IBM Watson or Amazon Lex among others). While these applications represent a valuable help and they might even be enough to solve some of the most basic scenarios (i.e., transactional chatbots), they usually involve a supervised process of definition, training and refinement, previous to deploy any chatbot to production.

Supervised vs. Unsupervised

Although these main platforms follow a supervised methodology, many enterprise use cases do not fit to this scenario. In a typical example (e.g., a customer-service chatbot), you may have a high-level idea of the topics in user utterances, but not to the level of the definition of the particular intents. Moreover, the only information that you usually have is a dump of conversations between users and agents. To use them in a supervised fashion would involve a lot of time and resources in order to explore, analyze and classify the data.

In this sense, wouldn’t be desirable to have an automatic process to analyze the data and extract the user intents? This is the scenario proposed by unsupervised methodologies: automatically detect patterns in the data that may be useful to organise the information according to them.

Using Lang.ai for Unsupervised Intent Induction

Our technology allows the automatic analysis of your chatbot data. In a previous post, we discussed about the advantages provided by our unsupervised technology to the chatbot development. For instance, following the previous customer service chatbot example, it allows you to analyze and explore the different intents addressed by your clients, identify them in new user utterances and give them a proper resolution. Let’s see how it works.

Firstly, we intend to detect the intents in the user utterances, as well as their related aspects (e.g., objects or entities): “Who did what to whom” (and perhaps also “when and where”). Such structural knowledge (i.e., intents plus their related aspects), usually referred as Frames, is an explicit prerequisite in many NLP tasks, Natural Language Understanding among them.

Usually, frames have been manually constructed by domain experts or linguists, thus constraining their application to a small number of specific and well-defined domains: let’s imagine to try to manually construct these frames for a dialogue system (e.g., SIRI), covering all the potential conversations, it would be crazy, wouldn’t it?. Therefore, the identification of such frames has to be addressed in an automatic fashion. This identification has been mainly tackled along two different lines (Jauhar and Hovy, 2017):

Modeling the frame structure by means of the selectional preference of predicates for certain arguments (Seaghdha, 2010); e.g., giving a high probability to the word “pasta” occurring as an argument of the word “eat”. Inducing the frames by clustering predicates and arguments in a joint framework (Lang and Lapata, 2011; Titov and Klementiev, 2012) which associates predicates such as “eat”, “consume”, “devour”, with a joint clustering of arguments such as “pasta”, “chicken”, “burger”.

In the particular field of chatbots, this induction is also a key aspect for the analysis of user requests and the conversation management. However, the way users speak to conversational interfaces makes this step slightly different from traditional natural language discourse analysis. For instance, in a dialogue system users directly request specific actions to be taken (I want to book a flight, turn off the lights, call my mom) with usually a unique intent per utterance (i.e., if there are more, they tend to be related by simple coordinators: and, but, or, …). In addition, when users realize they are talking to a non-human interface, they tend to simplify the message and use more direct requests, avoiding complex conversations.

Quote from Shakespeare’s Hamlet: “Neither a borrower nor a lender be; For loan oft loses both itself and friend, and borrowing dulls the edge of husbandry.” Typical Chatbot Request: I have a problem with my WiFi

In this sense, we relax the frame definition to base our representation on action-driven intents, which seem to be preferable in order to understand user utterances, thus focusing on two main roles: verb (what is the user requesting for) and object (objective of the user request):

I want to book [verb]a flight [object]

We base this process on a preliminary shallow-parsing approach to detect a set of initial verb-object candidates, which will then be modeled by means of the words appearing together with them. It follows the Distributional Hypothesis in which words in the same contexts tend to have similar meanings.

“You shall know a word by the company it keeps” Firth (1957)

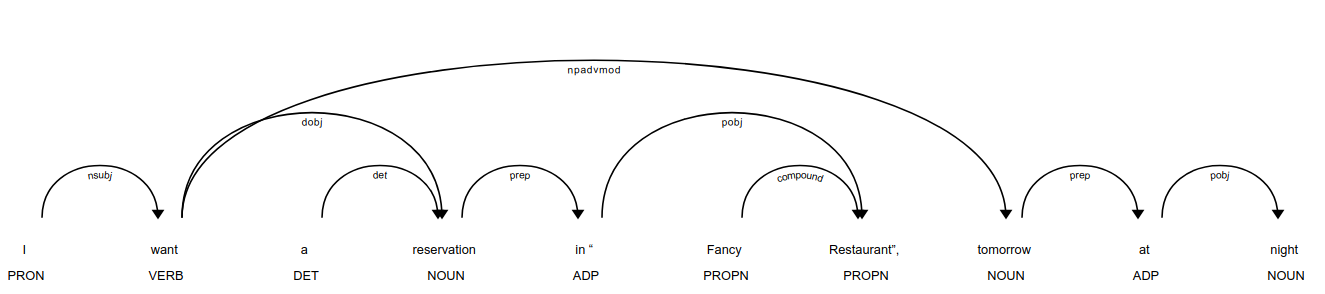

For instance, given the user request: I want a reservation in “Fancy Restaurant” tomorrow at night, this would be its dependency parsing (i.e., the analysis of the grammatical structure of the sentence):

From this parsing, we can identify the verb-object candidate want+reservation that is described by the contexts appearing in the sentence: (want, reservation), (reservation, in), (reservation, Restaurant), (tomorrow, night), …

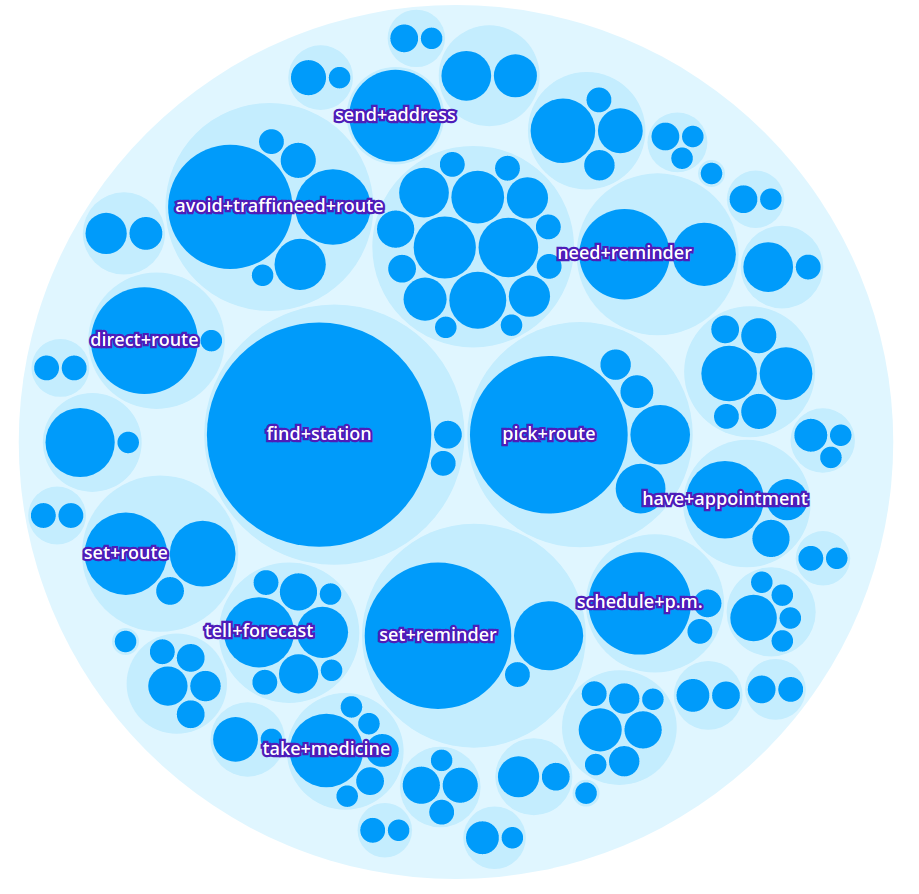

Taking this representation, our unsupervised approach is applied to identify the data as semantic object-action clusters comprising semantically related user utterances. In addition, based on the aggregation of each of the individual descriptions, a generative model is applied to induce a language model for each one of these groups. These clusters can be seen as the different intents requested by the users. For example, the following figure depicts an excerpt of the results for the Stanford Multi-Domain Dialog (SMD) dataset (Eric et al., 2017). SMD contains 3,031 task-oriented dialogs collected from 3 different domains: navigation, weather and scheduling.

Intent representation as seen in the Lang.ai Console

Intent representation as seen in the Lang.ai Console

As expected given the domains of the dataset, the detected intents include requests for addresses and directions (avoid+traffic, send+address), for reminders (take+medicine, set+reminder) or weather-related queries (tell+forecast).

Intents are semantically related into broader groups that include more general conversation topics. For example, the item avoid+traffic is related to the cluster including another intents used for requesting an alternative route that avoids heavy traffic, or the intent tell+forecast is related to other weather related intents.

Exploring the clusters in the Lang.ai console

Exploring the clusters in the Lang.ai console

This technology enables an easier definition of chatbot use cases, reducing their time-to-market by eliminating (or drastically reducing) the time spent in the user request analysis, the intent definition, as well as the training of supervised intent detection systems, while focusing on higher value-added tasks like the definition of the conversation flow. The identified intents plus their descriptions can be then used to analyze new user utterances, detect the user intents and redirect them to the conversation flow where they can be solved.

For instance, the following sentences have been annotated with the intent schedule+reminder. As can be seen, one sentence can be related to more than one of the inferred intents (e.g., set a reminder to take my medicine) or can be also annotated with features related to the intent (e.g., dinner, a specific event for which the reminder is needed).

If you are addressing the development of a chatbot, you can try Lang.ai for free by requesting an invite:https://lang.ai/developers.

Check the other articles in our Building Lang.ai publication. We write about Machine Learning, Software Development, and our Company Culture.

Bibliography

Jackie Chi Kit Cheung, Hoifung Poon & Lucy Vanderwende. 2013. “Probabilistic Frame Induction.” In Proceedings of NAACL-HLT 2013, 837–46. Mihail Eric, Lakshmi Krishnan, Francois Charette & Christopher D. Manning. 2017. “Key-Value Retrieval Networks for Task-Oriented Dialogue.” In Proceedings of the 18th Annual SIGdial Meeting on Discourse and Dialogue. Sujay Kumar Jauhar & Eduard Hovy. 2017. “Embedded Semantic Lexicon Induction with Joint Global and Local Optimization.” In Proceedings of the 6th Joint Conference on Lexical and Computational Semantics (SEM 2017). Joel Lang & Mirella Lapata. 2011. “Unsupervised Semantic Role Induction via Split-Merge Clustering.” In Proceedings of the 49th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies — Volume 1, 1117–26. Michael Ringgaard, Rahul Gupta & Fernando C. N. Pereira. 2017. “SLING: A Framework for Frame Semantic Parsing.” arXiv Preprint arXiv:1710.07032. Ivan Titov & Alexandre Klementiev. 2012. “Crosslingual Induction of Semantic Roles.” In Proceedings of the 50th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics — Volume 1, 647–56. Dmitry Ustalov, Alexander Panchenko, Andrei Kutuzov, Chris Biemann, & Simone Paolp Ponzetto. 2018. “Unsupervised Semantic Frame Induction Using Triclustering.” In Proceedings of the 56th Annual Meeting on Association for Computational Linguistics. Yansen Wang, Chenyi Liu, Minlie Huang, and Liqiang Nie. 2018. “Learning to Ask Questions in Open-Domain Conversational Systems with Typed Decoders.” In Proceedings of the 56th Annual Meeting on Association for Computational Linguistics.

Thanks to Fernando Agüero.

Bio: Angel Castellanos Gonzalez is Senior Data Scientist @ Lang.ai & Associate Professor @ IE.

Original. Reposted with permission.

Related: