Consider a model with parameters (\theta) and latent variables (\mathbf{Z}); the expectation-maximization algorithm (EM) is a mechanism for computing the values of (\theta) that, under this model, maximize the likelihood of some observed data (\mathbf{X}).

The joint probability of our model can be written as follows:

p(\mathbf{X}, \mathbf{Z}\vert \theta) = p(\mathbf{X}\vert \mathbf{Z}, \theta)p(\mathbf{Z}\vert \theta) $$

where, once more, our stated goal is to maximize the marginal likelihood of our data:

\log{p(\mathbf{X}\vert\theta)} = \log{\sum_{\mathbf{Z}}p(\mathbf{X, Z}\vert\theta)}

$$

An example of a latent variable model is the Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) model for uncovering latent topics in documents of text. Once finished deriving the general EM equations, we’ll (begin to) apply them to this model.

Why not maximum likelihood estimation?

As the adage goes, computing the MLE with respect to this marginal is “hard.” I loosely understand why. In any case, Bishop states:

A key observation is that the summation over the latent variables appears inside the logarithm. Even if the joint distribution (p(\mathbf{X, Z}\vert\theta)) belongs to the exponential family, the marginal distribution (p(\mathbf{X}\vert\theta)) typically does not as a result of this summation. The presence of the sum prevents the logarithm from acting directly on the joint distribution, resulting in complicated expressions for the maximum likelihood solution.

We’ll want something else to maximize instead.

A lower bound

Instead of maximizing the log-marginal (\log{p(\mathbf{X}\vert\theta)}) (with respect to model parameters (\theta)), let’s maximize a lower-bound with a less-problematic form.

One candidate for this form is (\log{p(\mathbf{X}, \mathbf{Z}\vert \theta)}) which, almost tautologically, removes the summation over latent variables (\mathbf{Z}).

As such, let’s derive a lower-bound which features this term. As (\log{p(\mathbf{X}\vert\theta)}) is often called the log-“evidence,” we’ll call our expression the “evidence lower-bound,” or ELBO.

Jensen’s inequality

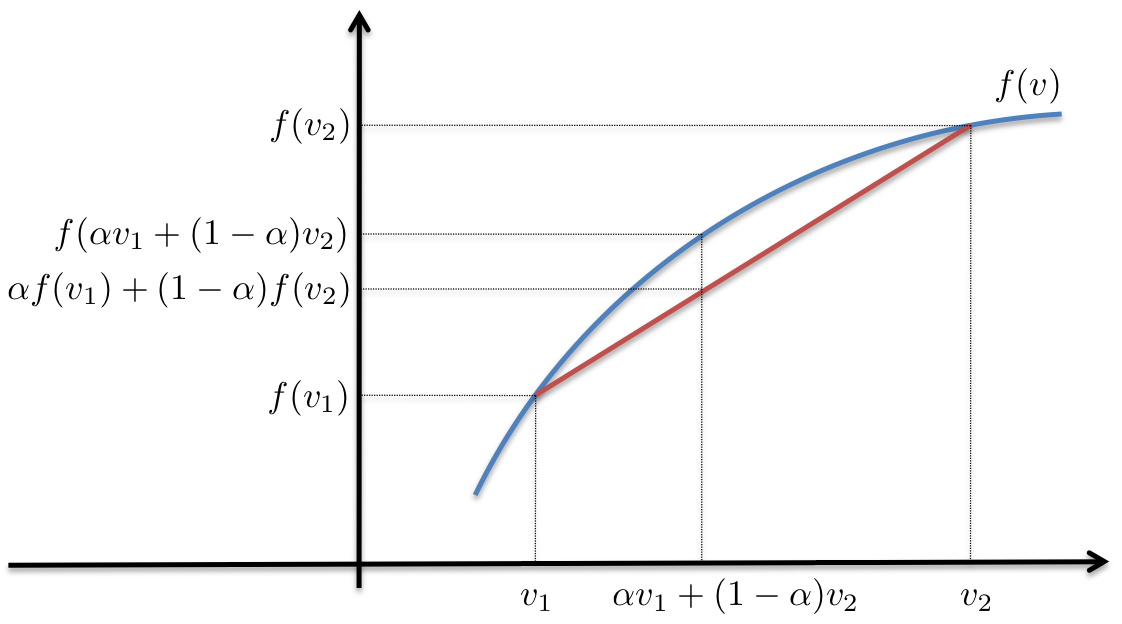

Jensen’s inequality generalizes the statement that the line secant to a concave function lies below this function. An example is illustrative:

First, we note that the red line is below the blue for all points for which it is defined.

Second, working through the example, and assuming:

-

(y = f(x) = \exp(-(x - 2)^2))

-

(v_1 = 1; v_2 = 2.5; \alpha = .3)

$$

\begin{align}

f(v_1) &\approx .3679

f(v_2) &\approx .7788

\alpha f(v_1) + (1 - \alpha)f(v_2) &\approx \bf{.6555}

\end{align}

we see that (\alpha f(v_1) + (1 - \alpha)f(v_2) \leq f(\alpha v_1 + (1 - \alpha)v_2)).

Finally, we arrive at a general form:

\mathop{\mathbb{E}{v}}[f(v)] \leq f(\mathop{\mathbb{E}{v}}[v])

$$

where (p(v) = \alpha).

Deriving the ELBO

In trying to align (\log{p(\mathbf{X}\vert\theta)}

= \log{\sum\limits_{\mathbf{Z}}p(\mathbf{X, Z}\vert\theta)}) with (f(\mathop{\mathbb{E}_{v}}[v])), we see a function (f = \log) yet no expectation inside. However, given the summation over (\mathbf{Z}), introducing some distribution (q(\mathbf{Z})) would give us the expectation we desire.

where (q(\mathbf{Z})) is some distribution over (\mathbf{Z}) with parameters (\lambda) (omitted for cleanliness) and known form (e.g. a Gaussian). It is often referred to as a variational distribution.

From here, via Jensen’s inequality, we can derive the lower-bound:

Et voilà, we see that this term contains (\log{p(\mathbf{X, Z}\vert\theta)}); the ELBO should be easy to optimize with respect to our parameters (\theta).

Before expanding further, let’s briefly restate basic results of Bayes’ theorem as applied to our model:

-

(p(\mathbf{Z}\vert\mathbf{X}, \theta) = \frac{p(\mathbf{X}, \mathbf{Z}\vert\theta)}{p(\mathbf{X}\vert\theta)})

-

(\log{p(\mathbf{X}, \mathbf{Z}\vert\theta)} = \log{p(\mathbf{Z}\vert\mathbf{X}, \theta)} + \log{p(\mathbf{X}\vert\theta)})

Additionally, we note that as (\log{p(\mathbf{X}\vert\theta)}) does not depend on (q(\mathbf{Z})), (\mathop{\mathbb{E}}_{q(\mathbf{Z})}\bigg[\log{p(\mathbf{X}\vert\theta)}\bigg] = \log{p(\mathbf{X}\vert\theta)}).

Continuing:

Putting it back together:

\log{p(\mathbf{X}\vert\theta)} = \mathop{\mathbb{E}}_{q(\mathbf{Z})}\bigg[\log{\frac{p(\mathbf{X, Z}\vert\theta)}{q(\mathbf{Z})}}\bigg] + \text{KL}\big(q(\mathbf{Z})\Vert p(\mathbf{Z}\vert\mathbf{X}, \theta)\big)

$$

The EM algorithm

The algorithm can be described by a few simple observations.

-

(\text{KL}\big(q(\mathbf{Z})\Vert p(\mathbf{Z}\vert\mathbf{X}, \theta)\big)) is a divergence metric which is strictly non-negative.

-

As (\log{p(\mathbf{X}\vert\theta)}) does not depend on (q(\mathbf{Z}))—if we decrease (\text{KL}\big(q(\mathbf{Z})\Vert p(\mathbf{Z}\vert\mathbf{X}, \theta)\big)) by changing (q(\mathbf{Z})), the ELBO must increase to compensate.

(For intuition, imagine we’re able to decrease (\text{KL}\big(q(\mathbf{Z})\Vert p(\mathbf{Z}\vert\mathbf{X}, \theta)\big)) to 0, which occurs when setting (q(\mathbf{Z}) = p(\mathbf{Z}\vert\mathbf{X}, \theta)).)

- If we increase the ELBO by changing (\theta), (\log{p(\mathbf{X}\vert\theta)}) will increase as well. In addition, as (p(\mathbf{Z}\vert\mathbf{X}, \theta)) now (likely) diverges from (q(\mathbf{Z})) in non-zero amount, (\log{p(\mathbf{X}\vert\theta)}) will increase even more.

The EM algorithm is a repeated alternation between Step 2 (E-step) and Step 3 (M-step). After each M-Step, (\log{p(\mathbf{X}\vert\theta)}) is guaranteed to increase (unless it is already at a maximum).

A graphic (Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning, Chapter 9) is further illustrative.

Initial decomposition

Here, the ELBO is written as (\mathcal{L}(q, \theta)).

E-step

Holding the parameters (\theta) constant, minimize (\text{KL}\big(q(\mathbf{Z})\Vert p(\mathbf{Z}\vert\mathbf{X}, \theta)\big)) with respect to (q(\mathbf{Z})). Remember, as (q) is a distribution with a fixed functional form, this amounts to updating its parameters (\lambda).

The caption implies that we can always compute (q(\mathbf{Z}) = p(\mathbf{Z}\vert\mathbf{X}, \theta)). We will below that this is not the case for LDA, nor for many interesting models.

M-step

In the M-step, maximize the ELBO with respect to the model parameters (\theta).

Expanding the ELBO:

we see that it decomposes into an expectation of the joint distribution over data and latent variables with respect to the variational distribution (q(\mathbf{Z})), plus the entropy of (q(\mathbf{Z})).

Maximizing this expression with respect to (\theta), we treat the latter as a constant.

EM for LDA

In the next few posts, we’ll use the Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) model as a running example.

Since the original paper is beautiful, I’ll default to citing its passages as much as possible.

Model

“Given the parameters (\alpha) and (\beta), the joint distribution of a topic mixture (\theta), a set of of (N) topics (\mathbf{z}), and a set of (N) words (\mathbf{w}) is given by:”

p(\theta, \mathbf{z}, \mathbf{w}\vert \alpha, \beta) = p(\theta\vert \alpha)\prod\limits_{n=1}^{N}p(z_n\vert \theta)p(w_n\vert z_n, \beta) $$

Log-evidence

The (problematic) log-evidence of a single document:

\log{p(\mathbf{w}\vert \alpha, \beta)} = \log{\int p(\theta\vert \alpha)\prod\limits_{n=1}^{N}\sum\limits_{z_n} p(z_n\vert \theta)p(w_n\vert z_n, \beta)d\theta} $$

NB: The parameters of our model are (\alpha) and (\beta), and ({\theta, \mathbf{z}}) are our latent variables.

ELBO

\mathop{\mathbb{E}}{q(\mathbf{Z})}\bigg[\log{\bigg(\frac{p(\theta\vert \alpha)}{q(\mathbf{Z})}}\prod\limits{n=1}^{N}p(z_n\vert \theta)p(w_n\vert z_n, \beta)\bigg)\bigg]

Peering at the denominator, we see that the expression under the integral is exponential in the number of words (N); for any non-trivial (N) and number of topics, it is intractable to compute. As such, the “ideal” E-step solution (q(\mathbf{Z}) = p(\theta, \mathbf{z}\vert \mathbf{w}, \alpha, \beta)) admits no analytical form.

In the next post, we’ll cover how to minimize this KL term with respect to (q(\mathbf{Z})) in detail. This effort will begin with the derivation of the mean-field algorithm.

Summary

In this post, we motivated the expectation-maximization algorithm then derived its general form. We then, briefly, applied it to the LDA model.

In the next post, we’ll expand this logic into mean-field variational Bayes, and eventually, variational inference more broadly.

Thanks for reading.