Benjamin Carlisle writes:

A year ago, I received a message from Anna Powell-Smith about a research paper written by two doctors from Cambridge University that was a mirror image of a post I wrote on my personal blog roughly two years prior. The structure of the document was the same, as was the rationale, the methods, and the conclusions drawn. There were entire sentences that were identical to my post. Some wording changes were introduced, but the words were unmistakably mine. The authors had also changed some of the details of the methods, and in doing so introduced technical errors, which confounded proper replication. The paper had been press-released by the journal, and even noted by Retraction Watch. . . . At first, I was amused by the absurdity of the situation. The blog post was, ironically, a method for preventing certain kinds of scientific fraud. [Carlisle’s original post was called “Proof of prespecified endpoints in medical research with the bitcoin blockchain,” the paper that did the copying was called “How blockchain-timestamped protocols could improve the trustworthiness of medical science,” so it’s amusing that copying had been done on a paper on trustworthiness. — ed.] . . . The journal did not catch the similarities between this paper and my blog in the first place, and the peer review of the paper was flawed as well.

OK, so far, nothing so surprising. Peer review often gets it wrong, and, in any case, you’re allowed to keep submitting your paper to new journals until it gets accepted somewhere, indeed F1000 Research is not a top journal, so maybe the paper was rejected a few times before appearing there. Or maybe not, I have no idea.

But then the real bad stuff started to happen. Here’s Carlisle:

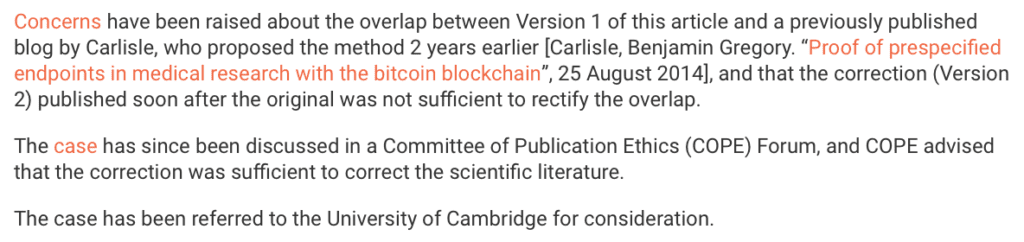

After the journal’s examination of the case, they informed us that updating the paper to cite me after the fact would undo any harm done by failing to credit the source of the paper’s idea. A new version was hastily published that cited me, using a non-standard citation format that omitted the name of my blog, the title of my post, and the date of original publication.

Wow. That’s the kind of crap—making a feeble correction without giving any credit—that gets done by Reuters and Perspectives on Psychological Science. I hate to see the editor of a real journal act that way.

Carlisle continues:

I was shocked by the journal’s response. Authorship of a paper confers authority in a subject matter, and their cavalier attitude toward this, especially given the validity issues I had raised with them, seemed irresponsible to me. In the meantime, the paper was cited favourably by the Economist and in the BMJ, crediting Iriving and Holden [the authors of the paper that copied Carlisle’s work]. I went to Retraction Watch with this story, which brought to light even more problems with this example of open peer review. The peer reviewers were interviewed, and rather than re-evaluating their support for the paper, they doubled down, choosing instead to disparage my professional work and call me a liar. . . . The journal refused to retract the paper. It was excellent press for the journal and for the paper’s putative authors, and it would have been embarrassing for them to retract it. The journal had rolled out the red carpet for this paper after all, and it was quickly accruing citations.

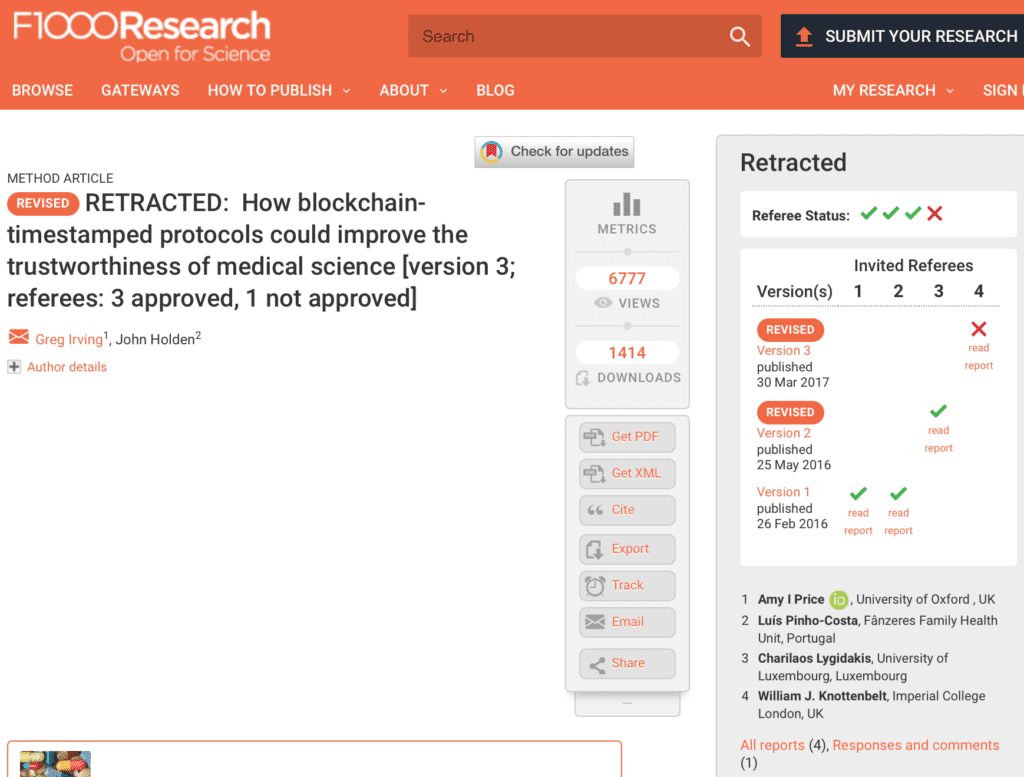

That post appeared in June, 2017. But then I clicked on the link to the published article and found this:

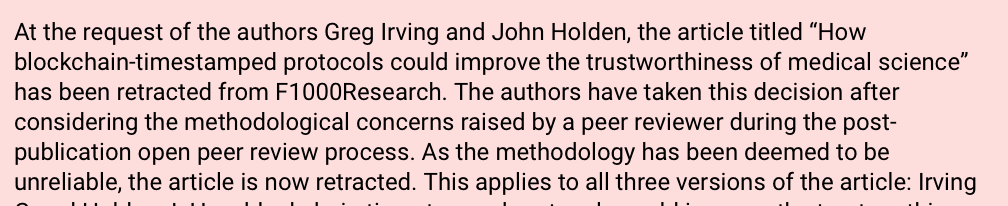

So the paper did end up getting retracted—but, oddly enough, not for the plagiarism.

On the plus side, the open peer review is helpful. Much better than Perspectives on Psychological Science. Peer review is not perfect. But saying you do peer review, and then not doing it, that’s really bad.

The Carlisle story is old news, and I know that some people feel that talking about this sort of thing is a waste of time compared to doing real science. And, sure, I guess it is. But here’s the thing: fake science competes with real science. NPR, the Economist, Gladwell, Freakonomics, etc.: they’ll report on fake science instead of reporting on real science. After all, fake science is more exciting! When you’re not constrained by silly things such as data, replication, coherence with the literature, you can really make fast progress! The above story is interesting in that it appears to feature an alignment of low-quality research and unethical research practices. These two things don’t have to go together but often it seems that they do.