Fritz Strack points us to this article, “When Both the Original Study and Its Failed Replication Are Correct: Feeling Observed Eliminates the Facial-Feedback Effect,” by Tom Noah, Yaacov Schul, and Ruth Mayo, who write:

According to the facial-feedback hypothesis, the facial activity associated with particular emotional expressions can influence people’s affective experiences. Recently, a replication attempt of this effect in 17 laboratories around the world failed to find any support for the effect. We hypothesize that the reason for the failure of replication is that the replication protocol deviated from that of the original experiment in a critical factor. In all of the replication studies, participants were alerted that they would be monitored by a video camera, whereas the participants in the original study were not monitored, observed, or recorded. . . . we replicated the facial-feedback experiment in 2 conditions: one with a video-camera and one without it. The results revealed a significant facial-feedback effect in the absence of a camera, which was eliminated in the camera’s presence. These findings suggest that minute differences in the experimental protocol might lead to theoretically meaningful changes in the outcomes.

We’ve discussed the failed replications of facial feedback before, so it seemed worth following up with this new paper that provides an explanation for the failed replication that preserves the original effect.

Here are my thoughts.

-

The experiments in this new paper are preregistered. I haven’t looked at the preregistration plan, but even if not every step was followed exactly, preregistration does seem like a good step.

-

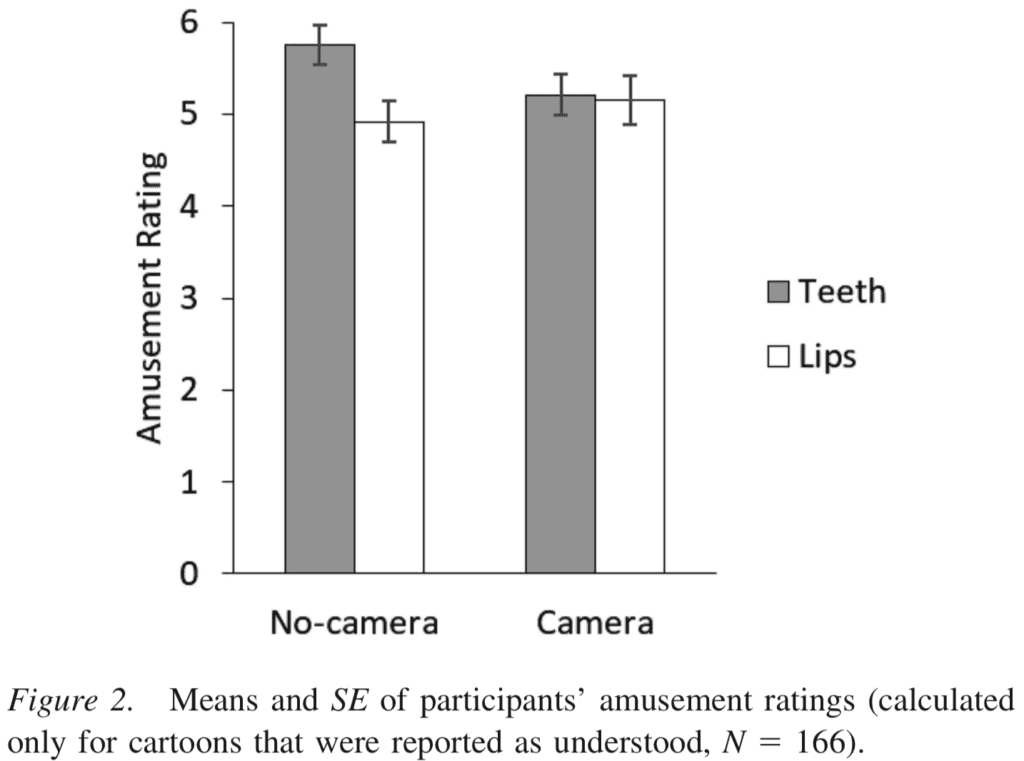

The main finding is the facial feedback worked in the no-camera condition but not in the camera condition:

-

As you can almost see in the graph, the difference between these results is not itself statistically significant—not at the conventional p=0.05 level for a two-sided test. The result has a p-value of 0.102, which the authors describe as “marginally significant in the expected direction . . . . p=.051, one-tailed . . .” Whatever. It is what it is.

-

The authors are playing a dangerous game when it comes to statistical power. From one direction, I’m concerned that the studies are way too noisy: it says that their sample size was chosen “based on an estimate of the effect size of Experiment 1 by Strack et al. (1988),” but for the usual reasons we can expect that to be a huge overestimate of effect size, hence the real study has nothing like 80% power. From the other direction, the authors use low power to explain away non-statistically-significant results (“Although the test . . . was greatly underpowered, the preregistered analysis concerning the interaction . . . was marginally significant . . .”).

-

I’m concerned that the study is too noisy, and I’d prefer a within-person experiment.

-

In their discussion section, the authors write:

Psychology is a cumulative science. As such, no single study can provide the ultimate, final word on any hypothesis or phenomenon. As researchers, we should strive to replicate and/or explicate, and any one study should be considered one step in a long path. In this spirit, let us discuss several possible ways to explain the role that the presence of a camera can have on the facial-feedback effect.

That’s all reasonable. I think the authors should also consider the hypothesis that what they’re seeing is more noise. Their theory could be correct, but another possibility is that they’re chasing another dead end. This sort of thing can happen when you stare really hard at noisy data.

-

The authors write, “These findings suggest that minute differences in the experimental protocol might lead to theoretically meaningful changes in the outcomes.” I have no idea, but if this is true, it would definitely be good to know.

-

The treatments are for people to hold a pen in their lips or their teeth in some specified ways. It’s not clear to me why any effects of this treatments (assuming the effects end up being reproducible) should be attributed to facial feedback rather than some other aspect of the treatment such as priming or implicit association. I’m not saying there isn’t facial feedback going on; I just have no idea. I agree with the authors that their results are consistent with the facial-feedback model.

P.S. Strack also points us to this further discussion by E. J. Wagenmakers and Quentin Gronau, which I largely find reasonable, but I disagree with their statement regarding “the urgent need to preregister one’s hypotheses carefully and comprehensively, and then religiously stick to the plan.” Preregistration is fine, and I agree with their statement that generating fake data is a good way to test it out (one can also preregister using alternative data sets, as here), but I hardly see it as “urgent.” It’s just one part of the picture.