Last year I took my family down to Oregon to experience a total solar eclipse. It was a magical experience.

The difference between a total eclipse and a partial eclipse is, well, like the difference between night and day! If you are in a region that is going to be close to a path of totality, and you decide that a 95% eclipse is good enough, I implore you to change your mind. Take the extra effort and move to location that will allow you to experience a full eclipse. I promise you that you will not regret it.

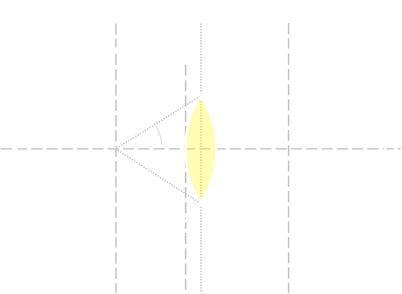

[Diagram not to scale]

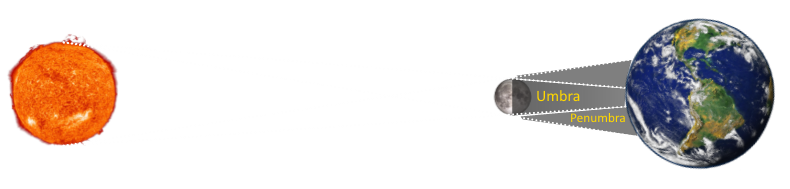

If you want more explicit details about how and why eclipses occur, you might like to read this article, but the summary is that, due to a wonderful coincidence, even though the Sun has a diameter approximately 400x that of our Moon, it is also approximately 400x further away. This means both objects subtend the same area of the sky, and when the Moon passes in front of the Sun, it can block it out. If the Sun-Moon-Earth line up perfectly (something called a sygyzy) then a total eclipse occurs.

|The Sun and Moon appear approximately the same size when viewed from the Earth.| |

| |

|

|

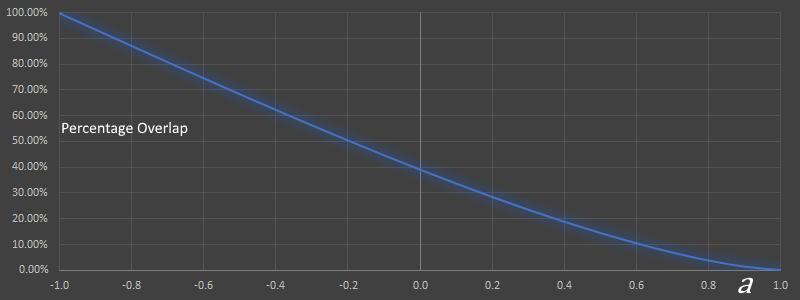

| |If the Sun and Moon don’t perfectly align, we get a partial eclipse (or even if they are going to perfectly align, it takes time for the two objects to slide in front of each other). What is the relationship between the percentage overlap and the distance between the two bodies? Let’s take a look …|

|If the Sun and Moon don’t perfectly align, we get a partial eclipse (or even if they are going to perfectly align, it takes time for the two objects to slide in front of each other). What is the relationship between the percentage overlap and the distance between the two bodies? Let’s take a look …|

Math Time

| |Let’s assume that both objects are sliding into each other along a line connecting their centers. I know, strictly speaking, for a Solar eclipse this is an approximation because the Moon and the Sun are on different ecliptic planes and this axis changes, but this is a second order consideration. The difference between the ecliptic planes is just 5.14°, and we’re talking about a small angle of overlap. |

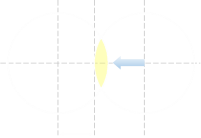

|Another way to think about this if two coins, or drink-coasters, are sliding over each other. What is the relationship between the distance a from center of one of the disks and the overlapping region (shown in the diagram on the right in yellow).We are assuming (for now) that both disks have the same radius, and normalize this to be one to simplify the math.|

|Let’s assume that both objects are sliding into each other along a line connecting their centers. I know, strictly speaking, for a Solar eclipse this is an approximation because the Moon and the Sun are on different ecliptic planes and this axis changes, but this is a second order consideration. The difference between the ecliptic planes is just 5.14°, and we’re talking about a small angle of overlap. |

|Another way to think about this if two coins, or drink-coasters, are sliding over each other. What is the relationship between the distance a from center of one of the disks and the overlapping region (shown in the diagram on the right in yellow).We are assuming (for now) that both disks have the same radius, and normalize this to be one to simplify the math.| |

|

We are assuming (for now) that both disks have the same radius, and normalize this to be one to simplify the math.

Try it out - where is 50% overlap?

If we wanted to slide the disks over each other so that the overlap region is half the area of a disk, what would the value of a be? (Making a 50% eclipse). Do you have a guess? How good are you are approximating the overlap percentages?

Below is a simple animation that allows you to slide the right disk over the left disk. (If you want to challenge yourself to see how good you are at estimating the overlap, toggle the ‘Show Percentage’ button first, then move the right disk, then click the button again to see how close you were).

The ‘Show Line’ button draws, and labels, the distance ‘a’ (as a ratio of the Radius), and the other two button toggle if the animation shows the sector and triangles which, as we will see below, are used for how to calculate the percentage overlap.

Calculation

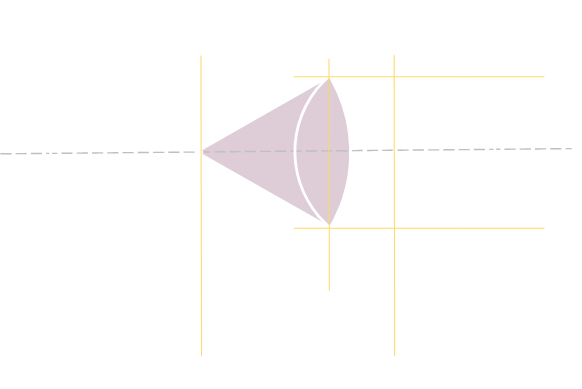

The overlap region we are trying to calculate is the ‘lens’ shaded in yellow below.

We can see that this lens is made up of two, symmetrical, half lenses.

The area of a half lens can be calculated by starting with the area of the sector (shown in green on the left diagram below), then subtracting the area of the triangle (shown in red), to leave the yellow half lens. Doubling this gives the area of the overlap.

The math is a little simpler if we work with the distance to the bisecting line d instead of the distance to the edge a. The relationship between these is simply:

From simple trig, this angle, α, can be determined by the inverse cosine (we normalized the radius to one unit). The area of a sector is half the angle of the sector in radians, and the angle of the sector is 2α. The coefficients cancel out to leave just α.

The area of a triangle is half the base multiplied by the height, and this is:

There’s a couple of ways we could go simplifying this, we could go with the double angle identities, but I went a different route of canceling out the cosines and simplifying the other term.

Plot

Here is a graph of the equation.

As you can see, when a=0 (the edge of one circle passes through the center of the other), the overlap is approximately 39.1%

To get to a 50% eclipse requires the value a ≈ −0.192

Different diameter disks

| |What happens if the two disks are of different diameters?Using the same principles we can generate a more generic formula for the overlap. The math is not much more complicated, but it looks that way because the terms get a little longer.|

|What happens if the two disks are of different diameters?Using the same principles we can generate a more generic formula for the overlap. The math is not much more complicated, but it looks that way because the terms get a little longer.|

Using the same principles we can generate a more generic formula for the overlap. The math is not much more complicated, but it looks that way because the terms get a little longer.

Here is a diagram showing the overlap between two disks, one of radius R, and another radius r.

Using Pythagoras, we can derive these equations:

Substituting these generates a formula for d1

Similarly for d2

This allows us to derive an equation for the variable y:

The area of the ‘right’ half of the lens can be calculated, as before, as the area of the sector of the left disk, subtracting the left triangle.

A corresponding formula can be derived for the ‘left’ half of the lens.

The total area of the overlap can be determined by adding these.

Substituting the earlier derived values for d1 and d2 gives this.

(This is sometimes quoted in this format):

Other Worlds

| |You now have all the tools required to calculate the eclipse overlap if you happen to be on a different planet (or different solar system) in which there is not the happy coincidence of having both objects subtend the same area of the sky.|

|You now have all the tools required to calculate the eclipse overlap if you happen to be on a different planet (or different solar system) in which there is not the happy coincidence of having both objects subtend the same area of the sky.|

You can find a complete list of all the articles here. Click here to receive email alerts on new articles.

Click here to receive email alerts on new articles.