Eleven months ago on a long train ride home, I wrote the first lines of code for a small platforming game. Little did I know that this prototype was the start of something much more than a just game – it was a dream that would become shared within an amazing team, and it was the greatest step in a personal journey that had begun over eight years ago.

Today, our game RAIN Project has been released on the Steam marketplace! Gameplay videos and screenshots are all over our Steam page, but in this post, I’ll be telling the story of RAIN’s development – where it all started, and how the game came to be.

The origins of (my) game development

If you look at the PC games market today, it’s all about the big names. You’ve got your League of Legends, Civilization, Overwatch. But back in 2010, it was a simpler time. And if you could get your hands on a computer, the first thing you did was load up the flash game websites.

The top place for entertainment! Or maybe I was just a kid with no money.

These sites were awesome. They were like buffets of entertainment, all for free. There were the classics, like Learn to Fly and Tanks, as well as the new stuff like Bloons TD 5.

But the best places were the user created sections. That’s where I was. See, back then there was no such thing as content regulation or quality control. Anything that you could build, you could share. And in this wild west of flash games was where I released my “masterpieces”.

ouch

Looking back now, I wasn’t exactly producing professional quality work. But for the little me, this was my pride and joy. Of course the critics descended, but I was just sitting there with a stupid grin, thinking “people out there are actually playing my games!”

It was around this time that I first heard about Touhou Project – a series of bullet-hell games made by single-man developer ZUN. I was awestruck. From the beautiful bullet patterns to lightning-fast boss fights, these were exactly the kind of games I was trying to make.

Left: Touhou 11, Subterranean Animism. Right: My attempt to recreate the game. Basically identical, right?

OK, so my Touhou clone didn’t have the best graphics or gameplay. But building it was some of the most fun I’d ever had, and that’s all that mattered!

So I was having a grand time in the world of flash games. I had my own little corner of the internet to share what I had created, and I even made a bit of pocket money from advertisements. But one weekend, I woke up to a sinking message.

Banned. Not for releasing too many crappy games, which would be fair. I was banned for being underage. See, legally a person must be 13 years of age to hold a Kongregate account. And in strict violation of this ever-important rule, 11-year-old me had his flash games career come to a sudden end.

The legend will never die

Well, seven years have passed since then. I’m older and more experienced now, and some mistaken people might even say I’ve matured. But that desire to built the Touhou-style bullet-hell game of my dreams still hasn’t gone away.

People often ask me, “why spend so much time on games? You could be doing so much else with your time”. And while it’s definitely true that I waste a lot of time on dumb things, I don’t think that building games is one of them. Game development has led me on some amazing adventures, and it’s even what got me interested in artificial intelligence in the first place.

While devastating at the time, getting booted off of Kongregate could have been a blessing in disguise. All this time I had been using Multimedia Fusion 2, a drag-and-drop game engine, to build my stuff. Finally, I had a chance to move on to more flexible tools – and with that, bigger ambitions!

In 2013, I learned the basics of iOS development in the cramped garage of a startup to build Blue, a bullet-hell with a minimalistic twist. I learned one crucial thing that summer – while building games might be easy, building good games was a lot of work! After three months, all I had accomplished was four minute-long levels.

For a while afterwards, I drifted on-and-off between a bunch of different projects, never quite concluding them. Without a clear target, I decided I had to buckle down and bring a game from start to finish. 2015 marked the birth of Skyflower, a procedurally generated bullet-hell dungeon crawler, that eventually made it onto Steam! At the time, I thought this was the height of accomplishment – but looking back, everything from programming to artwork was in severe need of improvement. Skyflower didn’t do so well on the market. But that experience of putting my all into something and failing to reach satisfaction would light a fire in my heart, that just wouldn’t seem to go away. I had to try again.

After the release of Skyflower, I needed a break from big game projects. Instead, 2016 became the year of game engines. Unlimited Bullet Festival, a scripting language for bullets, made it easy to throw together intricate bullet patterns in only a few lines of code. But I wanted to build an entire engine of my own – and that eventually came true with the Touhou web engine, a fully moddable and scriptable template for writing web-browser bullet-hell games in Javascript.

With the engine, I was able recreate three bosses from Touhou 8: Imperishable Night! Unfortunately, with school and obligations piling up, I just couldn’t find time to finish a full-fledged game with it.

The RAIN Project calls

If it’s not clear by now, this dream to build my perfect bullet-hell is a goal I’ve been chasing for a long time. Sure, things haven’t always proceeded smoothly – eight years and over fifty prototypes later, I’m still not satisfied with the results – but the next step was always calling. I wanted to build the game of my dreams. So all I had to do was go out there and build it.

And in summer 2017, the stars aligned. I had enough experience about game development and bullet-hells to bring a game from start to finish. My friends were on summer break, and with some convincing they were willing to help out. ZUN even put out a message stating that Touhou fangames could be published on Steam! At long last, the beginnings of RAIN Project began to form.

Today, I’m looking back with a smile. On July 3rd, 2018, RAIN Project released on Steam. It’s not the perfect game. And I’m definitely nowhere close to the perfect developer or leader. But what I can say with conviction is that I grabbed this chance and ran as far as I could. And what’s left is a game that I can proudly call my own – a bullet-hell adventure of my dreams.

What does it take to build a game?

Really, RAIN Project was a game that shouldn’t have been able to exist. We’re a development team of high schoolers, most of us with very little experience at all. Plus, this was during college applications season, so even finding the time to put in work was a challenge. We picked a pixel-art style, when none of us could draw in pixel art. For some fanatical reason, our ragtag group of friends was aiming to take on everything that releasing a game entailed ourselves – from programming and design, to art and music, and even marketing.

But in the words of Sanae Kochiya, “You can’t let yourself be held back by common sense”. Through what can only be some sort of miracle, we’re here today. RAIN isn’t the perfect game, but it’s a game we proudly raised from naive ideas and daydreaming to publication. We messed up, a lot, but with every mistake was a lesson to be learned. To be fair, I’ll admit I’m probably dramatizing things quite a bit. But now, looking back at it all, I’m going to attempt to detail the experience as a whole – what worked, what didn’t, and what could use just a bit a lot more work in the future.

Lesson one: Your designs are wrong.

My physics teacher always said to “keep your eyes on the big picture. But also keep in mind that the big picture will change”. With game development, this statement is truer than ever before.

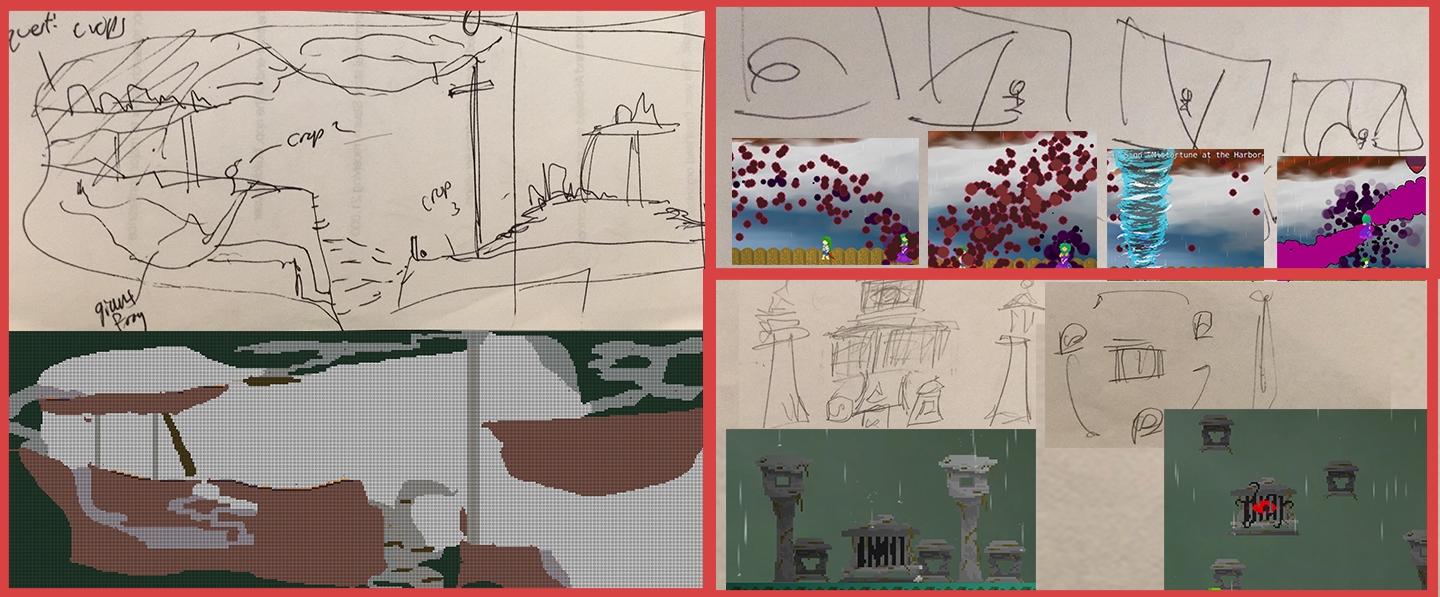

Old RAIN Project designs…. and how they ended up today.

If you asked me a year ago to describe what RAIN project would be like, it would be a whole different scene. RAIN’s core engine was originally for a fighting game I was prototyping. The level maps were originally designed as an open-world RPG adventure. Even the storyline has shifted dramatically, as it steadily molded around Sanae’s journey up the god’s mountain.

For me, design is one of the hardest aspects of game development – because it forces you to be a realist, when you really want to be a dreamer. In an ideal world, all my games would have pixel-perfect animations, branching dialogues and cutscenes, and enough content to last through the apocalypse. Of course, in practice, none of this will ever happen. The number one goal of every game developer is deceptively simple – make a game, and make it fun. And in a world where it’s easy to get lost chasing fancy features and shiny new ideas, keeping this vision in mind is crucially important.

For RAIN, that meant painfully saying no to a bunch of otherwise great suggestions from the team, simply because we didn’t have enough time or resources to implement them. Some levels, like the Moriya Shrine grounds or the Momiji miniboss fight, had to be scrapped if we wanted to reach our schedule.

At the same time, design is also one of my favorite aspects of game development – because you have the freedom to make whatever decisions you want! Unlike software programming or engineering, there’s no hard specifications you need to stick to. Remember that idea back at the dawn of flash games that “if you can build it, you can share it?” This magical statement still stands strong today.

Why are these in the game? Because I wanted them to be.

If I wanted to draw concept art in Minecraft blocks, make Aya’s wings ridiculously large, or reference some (in my definitely-biased opinion) inspirational scenes, all I had to do was make that happen!

Lesson two: The heart is in the team

Listen, from a technical standpoint, building a game alone is definitely possible. Some of the best games have come out of single-person teams – the Touhou series is even one of them! I spent a whole chunk of my life in solo development, yet today, I can say with confidence that working together with others is like a whole new world.

Of course, managing a team is hard. There’s been disagreements and arguments I wish I had handled better. Plus, I’m working with a bunch of friends in high school here – so while I’m glad that they’re good students, that duty of pulling everyone away from their studies to work on the game falls to me. The fight for time is always ongoing, and I’ve unfortunately become a regular participant.

sad times

The upsides, however, are definitely worth the effort. On a personal level, it’s like I’ve got a perpetual fire on my back, pushing me to finish the game and not give up. “You’re the one who dragged us into this mess”, I can imagine the team saying, “So you better pull us through to the end”. Also, putting my all into a project that we all want to see succeed is just fun. It’s admittedly a rare occasion due to the ever-present lack of time, but when everyone gets together to bounce ideas and debate for an afternoon, it’s an excitement like almost nothing else.

And that’s just the effects on me. From a practical standpoint, RAIN project couldn’t have happened without these guys. I can’t draw, I can’t compose music, and I can barely even manage the programming and design. But like miracle workers, these amazing people have stepped in and taken care of it beautifully, blowing my expectations away.

my saviors. thanks for joining me!!

Lesson three: If you don’t know what to do, do it anyways.

“OK, I’m going in blind. Absolutely no idea what I’m doing here”. It’s a phrase I’ve said almost countless times during RAIN’s development, and it’s one I’m sure I’ll be still be saying in the foreseeable future.

The best way to learn how to build a game is to build a game. And that means two things – there are going to be a lot of things you don’t know how to do, and you’re going to have to do them anyways. If I were a businessman or product manager, I probably wouldn’t approve a project like RAIN. There are so many unknowns, so many new things that could go wrong. But as a developer, and someone who can appreciate a good disaster, my eyes are gleaming with excitement.

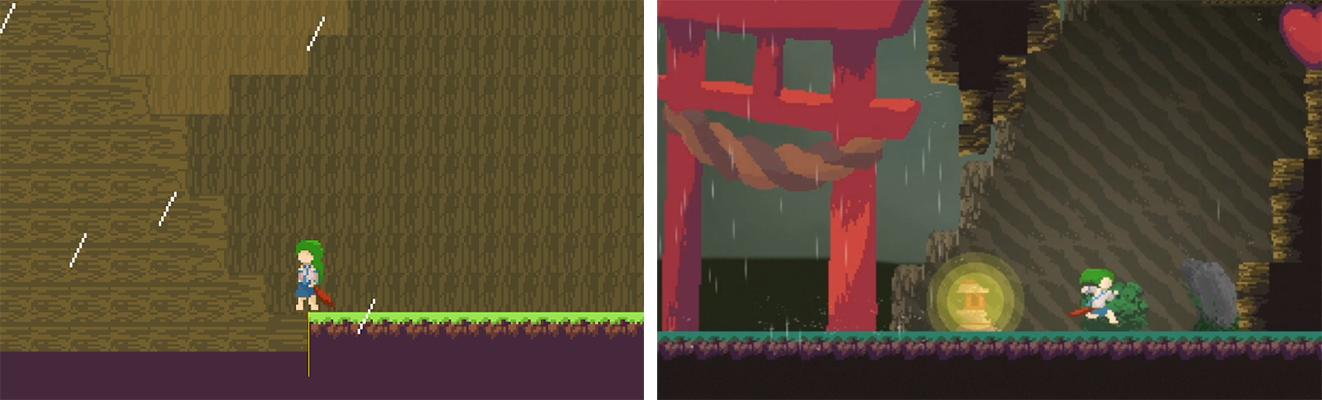

One of the first challenges was seemingly simple, yet carried a lot of depth behind it. How would we build interesting and varied levels, without spending twenty years on it? While hand-crafting each little segment would be ideal, it wasn’t a possibility given our resources. Instead, we decided on a tile-based system, so we could quickly sculpt out areas of the map. Unity doesn’t have tile-based support, so I had to write a loader for Tiled maps, which brought two import realizations with it. First off, levels can get very big, very fast. I eventually had to write a system to dynamically load and unload areas of the level to reduce CPU usage. Second, and perhaps more important, tiled levels were boring! We needed variation and decorations – so suddenly, this was a problem that needed not only level design, but artwork and sounds.

before and after of the starting level area

After the levels, the issue of boss fights came up. In Touhou games, bosses are multi-stage duels filled with thousands of bullets, often lasting longer than the level itself. In addition, the player has only two or three health points, so every stage carries a risk. I wanted to capture this same feeling of scale in RAIN project, but simply spamming bullets doesn’t transfer very well to platform games. After a lot of playing around, we were able to reach a balance between difficulty and intensity. Bosses in RAIN project aren’t only about reaction speed – most attacks are telegraphed, giving the player a chance to plan ahead. In this way, we can capture that intensity of attacks that cover half the screen, while still letting players clear the game.

First edition of Nitori’s spellcard. This did not work.

Lastly, an issue presented itself that would require a skill I had previously given little thought to – marketing! As we approached the halfway point of RAIN’s development, it became clear that we had to get the word out. The problem was, we had no clue where to even begin. We weren’t a big company, and we had a whopping zero connections in the gaming world. Evidently, we were going to have to spread the word on our own. While we updated a Twitter and website for a while, not many people were attracted. The biggest channel of communication we could get was actually when we began posting weekly updates to our Steam page. At first, I had absolutely no clue how to write these updates. But slowly, as we began entering the rhythm of development, the writing came easier – and as it turns out, a few screenshots and sentences can go a long way!

Lesson four: dance in the rain!

Game development can hard. It can be tiring, and at times you’ll feel like giving up or putting out a low-effort product.

That’s why in the torrential downpour that game dev can become, don’t run and take shelter. Take a lesson from Sanae – get out there, grab some friends, and dance through the storms! Tackle that level generator you’ve been so scared of, or draft the first outline of that daunting background scenery. Sure you’ll get wet, but the adventures you’ll have will be worth every second. And if by any chance you persevere through the harsh rains, the view at the end will be breathtaking.

Conclusion and beyond time

Whew, so I’ve finally finished writing. Maybe a bit too many rain metaphors on that last section, but if I named a whole game after it, then surely this much is fine. This post was definitely a a few deviations from my usual writing style – with most of my content being technical explanations for AI – but I wanted to get it all out. A few years from now, I might look back at the me of today and think “that guy was an idiot”. And it very well may be true. But for now, I’m happy to just lean back a bit and enjoy the scenery.

RAIN Project has been live on Steam for about a month now. During release week, I made the mistake of publishing the debug build for a total of eight hours, so some people got the unfortunate experience of insta-killing every enemy. While that left a bit of a mark on our reviews, some of the other feedback is fair – there are definitely a few bugs that slipped past and needed to get ironed out. Controller support, keyboard switching, and a soundtrack release are also on the menu. So keep a lookout for that.

As for me, RAIN Project has been a great step in my everlasting game development journey. But it won’t be the last. Keep an eye out – and next time, I’ll see you on the market!

This post is an adaptation of a talk I gave at Gunn Engineering Night a few months ago.