Pierre Jacob, Lawrence Murray, Chris Holmes, Christian Robert write:

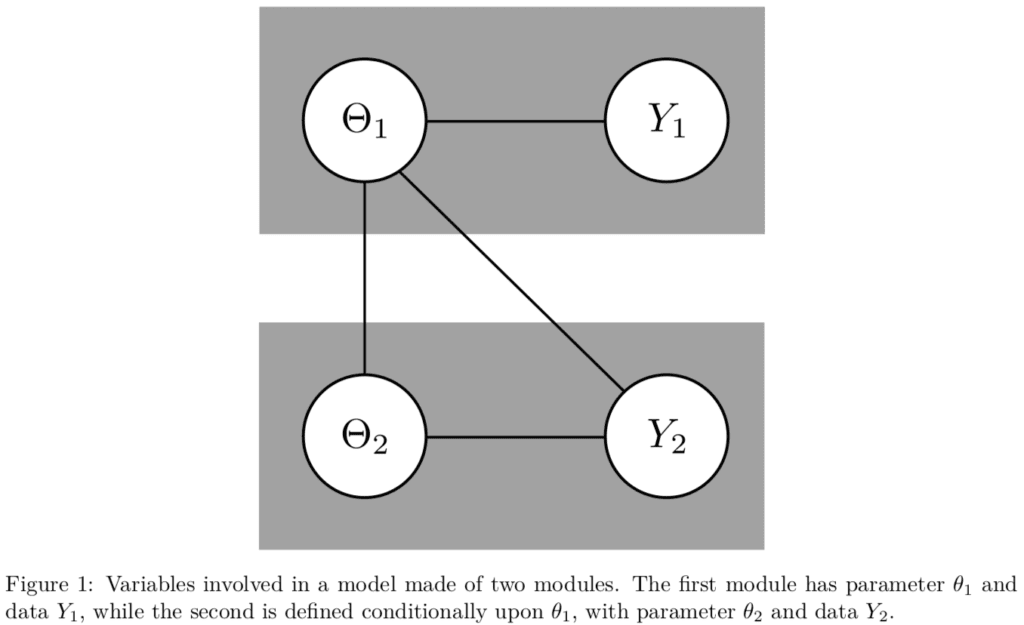

In modern applications, statisticians are faced with integrating heterogeneous data modalities relevant for an inference, prediction, or decision problem. In such circumstances, it is convenient to use a graphical model to represent the statistical dependencies, via a set of connected “modules”, each relating to a specific data modality, and drawing on specific domain expertise in their development. In principle, given data, the conventional statistical update then allows for coherent uncertainty quantification and information propagation through and across the modules. However, misspecification of any module can contaminate the estimate and update of others, often in unpredictable ways. In various settings, particularly when certain modules are trusted more than others, practitioners have preferred to avoid learning with the full model in favor of approaches that restrict the information propagation between modules, for example by restricting propagation to only particular directions along the edges of the graph. In this article, we investigate why these modular approaches might be preferable to the full model in misspecified settings. We propose principled criteria to choose between modular and full-model approaches. The question arises in many applied settings, including large stochastic dynamical systems, meta-analysis, epidemiological models, air pollution models, pharmacokinetics-pharmacodynamics, and causal inference with propensity scores.

The key idea is that full joint inference can lead to problems, and modular inference is a possible short-term solution, to the extent that the full joint model is misspecified. This suggests that it can make sense to try the computations both ways—joint and modular—and examine differences in the resulting inferences.

To put it another way, if we think of the joint model as a baseline, then we can think of a modular fit as a sort of model check.

Ultimately I think the best way forward is to expand the joint model so that it fits both datasets and makes substantive sense—see here for an example—but it also seems like a good idea to have tools for revealing model misspecifications that are relevant to particular inferences of interest, hence our interest in the above article.