While deep learning can be applied generally, much of the excitement around it has stemmed from significant breakthroughs in two main areas: computer vision and natural language processing. Practitioners have typically applied convolutional neural networks (CNNs) to spatial data (e.g. images) and recurrent neural networks (RNNs) to sequence data (e.g. text). However, a recent research paper has shown that convolutional neural networks are not only capable of performing well on sequential data tasks, but they have inherent advantages over recurrent networks and may be a better default starting point.

CNNs were designed originally to take advantage of spatial structure in the input data; for example, a pixel in an image is strongly related to nearby pixels. Sequence data also exhibits a “spatial” structure of sorts, where a particular word is strongly related to surrounding words. The observation is not new, though, and CNNs have been successfully applied to tasks involving sequences for decades. These applications have traditionally been things like sentiment or topic classification, where the output has the freedom to inspect every element in the input sequence. Until fairly recently, CNNs were not popular choices for tasks which involve mapping an input sequence to an output sequence (e.g., time series forecasting).

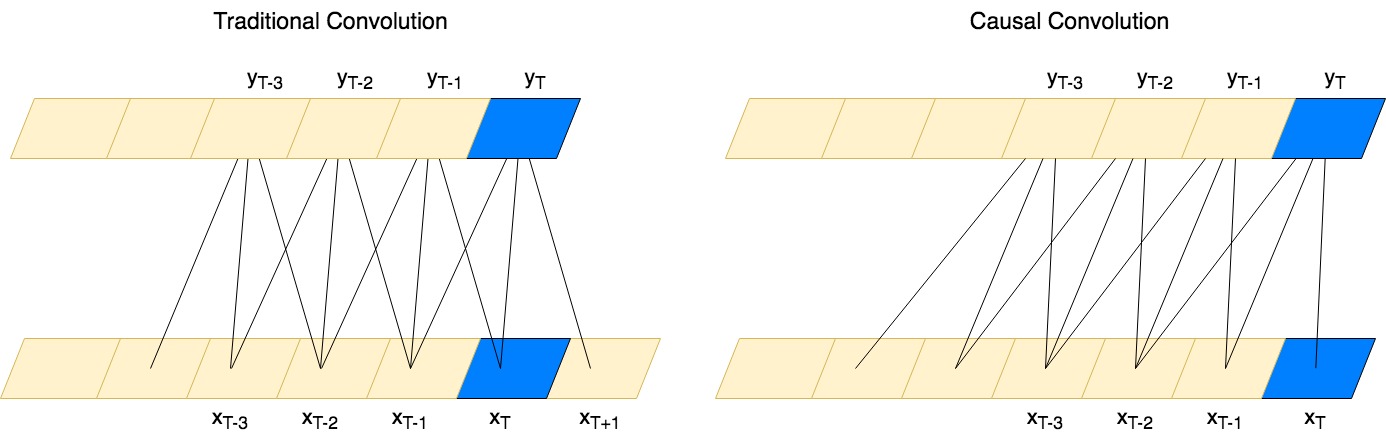

Vanilla CNNs applied to sequence forecasting have two pitfalls - the output incorporates input from both the past and the future, and they struggle to “see” or “remember” events in the distant past. Luckily, there are solutions for these two shortcomings: causal convolutions and dilated convolutions, respectively. A causal convolution adjusts the convolution kernel to only look at data in the past:

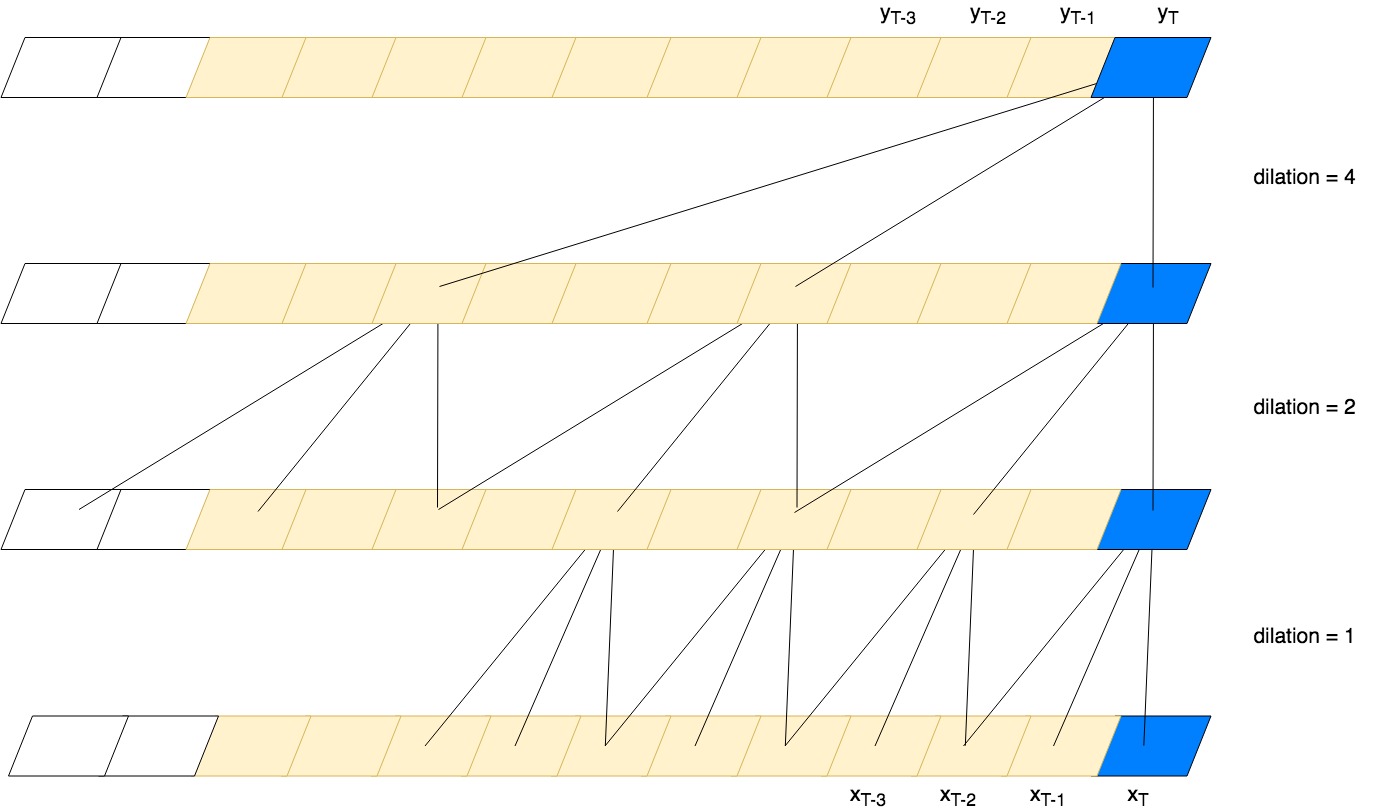

while dilated convolutions introduce gaps that allow the output to incorporate information from the distant past:

CNNs that have been modified for use in temporal domains are called temporal convolutional networks or TCNs. One of the main benefits of using TCNs for sequence modeling tasks is that the convolutions can be computed in parallel since the output at a given timestep does not need to wait for previous timesteps. This is in contrast to an RNN, where each prediction must wait for all previous predictions. One potential downside to TCNs is that they do not encode the history of the sequence in a single hidden state like RNNs do, but instead require the entire input sequence to generate predictions.

The authors of the paper present results that show that simple TCNs can beat popular recurrent architectures at sequence modeling tasks that have traditionally only used recurrent networks. While it would be counter-productive to declare a winner, it may be time to question our assumptions and consider TCNs as a first-class citizen for sequence modeling. If you’ve had success with using convolutional networks for time series or sequence modeling, we’d love to hear more about it!