This is a post about my takeaways from the DALI workshop on the Goals and Principles of Representation Learning which we co-organized with DeepMinders Shakir Mohamed and Andriy Mnih and Twitter colleague Lucas Theis. We had an amazing set of presentations, videos are available here.

DALI is my favourite meeting of the year. It’s small and and participants are all very experienced and engaged. To make most of the high quality audience we decided to focus on slightly controversial topics, and asked speakers to present their general thoughts, their unique perspectives and opinions rather than talk about their latest research project. Broadly, we asked three types of questions:

-

What tasks do we use unsupervised representation learning for?

-

What principles can help us do well on the tasks

-

How can we turn principles into to actual objective functions and algorithms.

Task → Principle → Loss functon → … → Algorithm

From my perspective, the end-goal of any area of ML research should be for each algorithm to have a justification from first principles. Like the chain above starting from the Task all the way down to the precise algorithm we’re going to run.

In my machine learning cookbook post I reviewed a number of fairly well understood problem transformations which one could apply to the bottom of this chain, typically to turn an intractable optimisation problem to a tractable one: variational inference, evolution strategies, convex relaxations, etc. In the workshop we focussed on the top of the chain, the computational level understanding: Do we actually have clarity on the ultimate task we solve? If this the task is given, is the principle we’re applying actually justified? Is the loss function consistent with the principle?

Transfer learning

One thing that most speakers and attendees seemed to agree on is that the most interesting and most important task we use unsupervised representation learning for is to transfer knowledge from large datasets to new tasks. I’ll try to capture one possible formulation of what this means:

-

we have some large auxiliary dataset $\mathcal{D}$.

-

we have a future ML task $T$ which we have to learn to solve in the future. We may not have complete knowledge as to what this task is.

-

The goal of transfer learning is to increase our data-efficiency in solving $T$, using side information derived from the auxilliary dataset $\mathcal{D}$.

There are many possible extensions of this basic setup. For example we may have a distribution of tasks, rather than a single task.

Disentanglement

One of the principles we discussed was disentanglement. It is somewhat unclear what exactly disentanglement is, but one way to capture this is to say “each coordinate in the representation corresponds to one meaningful factor of variation”. Of course this is kind of a circular definition inasmuch as it’s not easy to define a meaningful factor of variation. Irina defined disentangled representations as “factorized and interpretable”, which, as a definition, has its own issues, too.

In the context of transfer learning though, I can see a vague argument for why seeking disentanglement might be a useful principle. One way to improve data efficiency of a ML algorithm is to endow it with inductive biases or to reduce the complexity of the function class in some sense. If we believe that future downstream tasks we may want to solve can be solved with simple, say linear, models on top of a disentangled representation, then seeking disentanglement makes sense. It may be possible to use this argument itself to formulate a more precise definition of or objective function for disentanglement.

Self-supervision

The idea of self-supervision also featured prominently in talks. Self-supervision is the practice of defining auxiliary supervised learning tasks involving the unlabelled data, with hopes that solving these auxiliary tasks will require us to build representations which are also useful in the eventual downstream task we’d like to solve. Autoencoders, pseudolikelihood, denoising, jigsaw-puzzles, temporal-contrastive learning and so on are examples of this approach.

One very interesting aspect Harri talked about was the question of relevance? How can we make sure that an auxiliary learning task is relevant for the primary inference task we need to solve. In a semi-supervised learning setup Harri showed how you can adapt an auxiliary denoising task to be more relevant: you can calculate a sort of saliency map to determine which input dimensions the primary inference network pays attention to, and then use saliency-weighted denoising as the auxiliary task.

Are representations the solution?

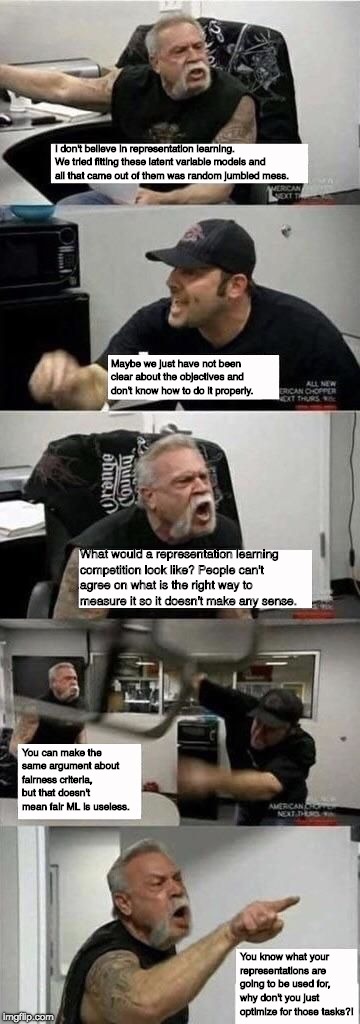

After the talks we had an open discussion session, hoping for a heated debate with people representing opposing viewpoints. And the audience really delivered on this. 10 minutes or so into the discussion Zoubin walked in and stated “I don’t believe in representation learning”. I tried to capture the main points in the argument (dad being anti-representation) below:

Retrospectively, I would summarise Zoubin’s (and others’) criticism as follows: If we identified transfer learning as the primary task representation learning is supposed to solve, are we actually sure that representation learning is the way to solve it? Indeed, this is not one of the questions I asked in my slides, and it’s a very good one. One can argue that there may be many ways to transfer information from some dataset over to a novel task. Learning a representation and transferring that is just one approach. Meta-learning, for example, might provide another approach.

Summary

I have really enjoyed this workshop. The talks were great, participants were engaged, and the discussion at the end was a fantastic ending for DALI itself. I am hoping that, just like me, others have left the workshop with many things to talk about, and that the debates we had will inspire future work on representation learning (or anti-representation learning).