In my previous post on the new open source Python Bounter library we discussed how we can use its HashTable to quickly count approximate item frequencies in very large item sequences. Now we turn our attention to the second algorithm in Bounter, CountMinSketch (CMS), which is also optimized in C for top performance.

(Shoutout to dav009 who already ported our CountMinSketch to Golang and provided some extra measurements.)

Count-min sketch is a simple yet powerful probabilistic data structure for estimating frequencies (also called counts) in very large datasets of elements (aka objects), closely related to Bloom filters. Wikipedia provides an excellent overview of the CMS algorithm. There are also several other resources out there that can help you get the idea, including this site dedicated to the algorithm and several great blogs.

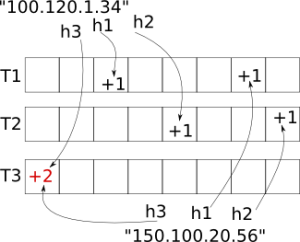

In short, you can visualize CMS as working over a two dimensional “table” of cells called “buckets”. This table has depth rows and width columns. Each bucket in the table stores a single number. Any element to be processed by CMS is mapped to depth different buckets, one bucket per row. Which bucket gets mapped in each row is calculated using hashing: we hash the input object using a row-specific salt, to make the hash functions row-wise independent. Then to increment that object’s count, we increment the value of each of its mapped buckets. To get the object’s (approximate) count later, we find the minimum value across all its mapped buckets. That’s it!

Inserting two objects, the strings “100.120.1.34” and “150.100.20.56” into a Count-Min Sketch table of depth=3 and width=8. Note the collision in the bottom-left bucket. Image courtesy of L. Kozma.

What about hash collisions? Clearly, two different objects can end up mapping to one or more of the same buckets. The nice approximative properties of CMS stem from the fact that we expect objects that collide in one row not to collide in a different row.

Given an object, the value in each bucket is an overestimation of its frequency count: it can be larger than the real count (due to a collision), or equal to it (no collision), but it can never be smaller. We can also say that there is a bias in one direction (up).

The CMS count for an object is estimated by retrieving the mapped bucket values from each row and returning the smallest of these numbers. This will be the one closest to the real value (though still possibly overestimated). With more rows, we have a better chance of finding a bucket that has had no collision, or at least find one where the error from overestimation is the smallest.

To improve on this basic idea, Bounter always uses the conservative update heuristic. While incrementing, after finding the appropriate bucket in each row, only those buckets that share the lowest value are updated (the remaining buckets must already have been affected by a collision and overestimated). This significantly mitigates the collision error and greatly improves the overall precision of the algorithm, compared to the basic version.

On top of this algorithm, for user convenience, Bounter adds a HyperLogLog structure to estimate the overall number of distinct elements inserted into the CMS table so far, and also maintains a precise tally of all these elements.

Usage

To initialize CountMinSketch, use either one of these methods:

from bounter import bounter, CountMinSketch

if you don’t need key iteration, Bounter chooses the CMS algo automatically

counts = bounter(need_iteration=False, size_mb=256)

or you can choose it explicitly yourself

counts = CountMinSketch(size_mb=256) # specify max memory, table size calculated automatically counts = CountMinSketch(width=8388608, depth=8) # specify concrete table size

counts.size() # print overall structure size in bytes 268435456 counts.width # buckets per table row 8388608 counts.depth # number of table rows 8

Count frequencies just like with HashTable:

counts.update([‘a’, ‘b’, ‘c’, ‘a’]) counts.increment(‘b’) counts.increment(‘c’, 2) # larger increments work too! print(counts[‘a’]) 2

CountMinSketch does not support iteration of elements. This is because the keys (the objects themselves, or their hashes) are never stored. The += syntax for increment is also unsupported. This is because assignment is unsupported, and Python treats += only as shorthand for calling __getitem__, incrementing the result, and feeding it into __setitem__.

The depth parameter

By increasing the depth parameter, you can increase the chance of avoiding a collision in at least one row and thus improve the accuracy of the results. However, this also increases the table size and the processing time of each insert or count operation. In our experiments, we had the best results with depths between 8 to 16, meaning we used 8-16 different hashes per object. Above that, investing memory into additional width (as opposed to depth) yields a much better marginal improvement.

Logarithmic counters

Each bucket of the standard algorithm takes 32 bits, and is thus able to represent object counts between 0 and 4,294,967,295. Bounter also implements approximate counting in the buckets, reducing the size of each bucket while extending the value range. The idea of approximate counting is to represent a range of values with a single counter value, stepping to the next value only sometimes, probabilistically. For instance, to step from the bucket value 5 (representing object counts of 32-63) to 6 (representing 64-127), we need to pass a random test with a 1/32 chance of success. This means we need an average of 32 attempts to take this one step.

This “base-2” setup of doubling the range and halving the probability makes for an intuitive example, but base-2 would be too crude and imprecise for Bounter. In reality, we use the same principle but with a lower base: we take more steps between each power of 2 (8 or 1024 steps). So, as an example with 8 steps, we would step from count range 32-35 (represented by bucket value 24) to 36-39 (25) with p=1/4, then to 40-43 (26) with p=1/4, and so on with the same p until 64-71 (32), from which we would step to 72-79 (33) with p=1/8.

counts = bounter(need_iteration=False, size_mb=254, log_counting=1024) counts = bounter(need_iteration=False, size_mb=254, log_counting=8)

Log1024 is a 16-bit counter which is precise for values up to 2048. Larger values are off by ~2%. The maximum representable value is around 2^71.

Log8 fits into just 8 bits and is precise for values up to 16. Larger values are off by ~30%, with the maximum representable value around 2^33.

Using these counters introduces a different kind of error. We call it the “counter error”, as opposed to “collision error” which comes from bucket collisions. Unlike the collision error, the counter error is unbiased. Also, while collision errors affect primarily small values, the counter error only occurs for larger values. By using approximate counters, we can trade some of the collision error (freeing up to 4x more buckets in the same space) for the counter error.

So much for theory. Let us look at some measurements and their visualisations to better understand the trade-offs we are making.

Evaluation

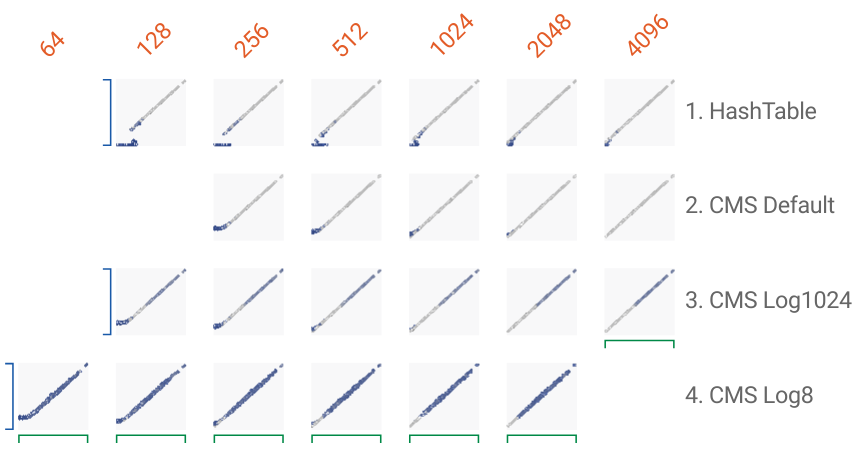

We use the same setup as the last time with HashTable: First, we count all word bigrams across all ~4 million articles from the English Wikipedia. Then, we use their counts to determine phrase collocations and calculate the resulting precision, recall and F1 values for this task.

We include the Hashtable results from the last part in the visualisations, so that you can directly compare against its results.

What about hash collisions? Clearly, two different objects can end up mapping to one or more of the same buckets. The nice approximative properties of CMS stem from the fact that we expect objects that collide in one row not to collide in a different row.

The CMS count for an object is estimated by retrieving the mapped bucket values from each row and returning the smallest of these numbers. This will be the one closest to the real value (though still possibly overestimated). With more rows, we have a better chance of finding a bucket that has had no collision, or at least find one where the error from overestimation is the smallest.

On top of this algorithm, for user convenience, Bounter adds a HyperLogLog structure to estimate the overall number of distinct elements inserted into the CMS table so far, and also maintains a precise tally of all these elements.

Count frequencies just like with HashTable:

The depth parameter

By increasing the depth parameter, you can increase the chance of avoiding a collision in at least one row and thus improve the accuracy of the results. However, this also increases the table size and the processing time of each insert or count operation. In our experiments, we had the best results with depths between 8 to 16, meaning we used 8-16 different hashes per object. Above that, investing memory into additional width (as opposed to depth) yields a much better marginal improvement.

This “base-2” setup of doubling the range and halving the probability makes for an intuitive example, but base-2 would be too crude and imprecise for Bounter. In reality, we use the same principle but with a lower base: we take more steps between each power of 2 (8 or 1024 steps). So, as an example with 8 steps, we would step from count range 32-35 (represented by bucket value 24) to 36-39 (25) with p=1/4, then to 40-43 (26) with p=1/4, and so on with the same p until 64-71 (32), from which we would step to 72-79 (33) with p=1/8.

Log8 fits into just 8 bits and is precise for values up to 16. Larger values are off by ~30%, with the maximum representable value around 2^33.

So much for theory. Let us look at some measurements and their visualisations to better understand the trade-offs we are making.

Evaluation

We include the Hashtable results from the last part in the visualisations, so that you can directly compare against its results.

You can see these accuracy charts in action and inspect individual errors (shades of blue) interactively, using Google’s awesome FacetsDive tool. Click here to open the plot above in a new, interactive browser window.

With limited memory, each algorithm produces a characteristic error, which is best understood when looking at the Facets visualisation and inspecting the concrete examples there.

Just as with HashTable, you can use the quality() function to get the ratio of the cardinality of the inserted items to the CMS capacity (total number of buckets). For a quality near or below 1, the results show no collision error.

The following table hints at the relationship of Quality (the number returned by quality(), the first number in the table) and F1 score (the second bold number in the table, higher is better, 1.0 is perfect) for several combinations of counter algorithms and RAM footprint. The blank cells represent combinations which were not tested.

As you can see, we can reach (or get very close) to the perfect F1 score of 1.0 with Quality values around 3.