Like many of you, I thoroughly enjoyed Ali Rahimi’s NIPS talk in response to winning the test-of time award for their work on random kitchen sinks. I recommend everyone to watch it if you haven’t already.

I also read Yann LeCun’s rebuttal to Ali’s talk. He says what Ali calls alchemy is in fact engineering. Although I think Yann ends up arguing against points Ali didn’t make in his talk, he raises important and good points about the different roles that tricks, empirical evidence and theory can play in engineering.

I wanted to add my own thoughts and experiences to the mix.

Different modes of innovation

We can think about machine learning knowledge as a graph, where methods are nodes and edges represent connections or analogies between the methods.

Innovation means growing this graph, which one can do in different ways:

-

add new nodes: This is about thinking outside the box: about discovering something completely new and quirky that, hopefully, works. Recent examples of this type of ML innovation include herding, noise-as-targets, batch-norm, dropout or GANs. You added a new node to the graph, maybe weakly connected to the rest of the graph, but your reasoning may not be very clear to most people at first.

-

discover connections between existing nodes: This is about finding explanations for new methods. Interpreting k-means as expectation-maximization, dropout as variational inference, stochastic gradient descent as variational inference, GANs as f-GANs, batchnorm as natural gradients, denoising autoencoders as score matching, etc. These are all hugely influential pieces of work, and we sorely need this kind of work in ML as these connections often allow us to improve or generalize techniques and thereby to make more predictable progress.

-

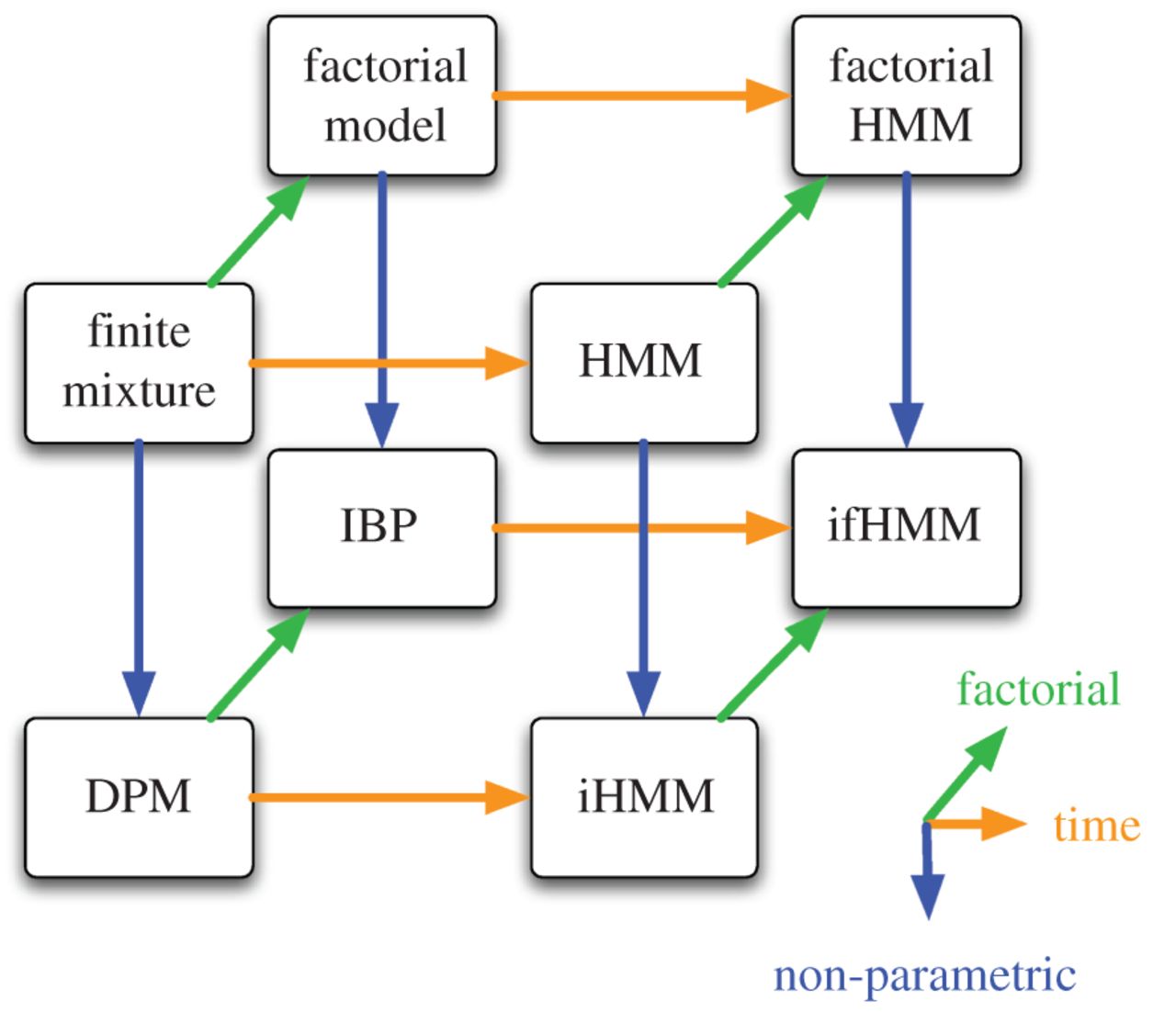

complete patterns: This is about analogical reasoning. You notice incomplete patterns in the graph, and infer that some nodes must exist by completing the pattern. At the Sam Roweis Symposium at NIPS 2010 I remember Zoubin Ghahramani making a joke about how he and Sam wrote a bunch of papers together basically for free by completing hypercubes, just like the one below. Long time readers of my blog will know that Sam and Zoubin’s unifying review is one of my all-time favourite papers. Note that this ‘pattern completion’ happens outside the Bayesian world, too: see e.g. bi-directional convolutional RNNs or PixelGAN Autoencoders.

Each of these modes of innovation are important in the process of building knowledge and moving forward. Our community tends to celebrate and glorify #1 (as long as the paper has the reigning buzzword in the title). Individually, we are incentivized to write loads of papers, so we spend most of our time on #3 which is arguably the lowest risk incremental project. I don’t think we reward or encourage #2 enough, and to me, this is one of the main messages in Ali’s talk. By focussing too much on benchmarks, datasets, and empirical results, we are actually creating barriers for people whose main contribution would be explaining why methods work or don’t work.

It’s easy to forget what the original GAN paper’s results looked like. These were really good back then and would be laughable today:

GANs were, arguably, a highly influential, great new idea. Today, that same paper would be unpublishable because the pictures don’t look pretty enough. Wasserstein GANs were a great idea, and frankly, to recognize it is a good idea and I don’t need to look at experimental results at all.

The same way Yann argues neural nets were unfairly abandoned in the 90s because of the lack of convergence guarantees convex optimization methods enjoy, today we are unfairly dismissing any method or idea that does not produce state-of-the-art or near-SOTA results. I once reviewed a paper where another reviewer wrote “The work can be novel if the method turns out to be the most efficient method of […] compared to existing methods”. This is at least as wrong as dismissing novel ideas for lack of theory (which is, BTW, not what Ali suggested).

It’s Okay to use non-rigorous methods, but…

it’s not okay to use non-rigorous evaluation

As far as I’m concerned, I’m now comfortable with using methods that are non-rigorous or for which the theoretical framework is underdeveloped or does not exist. However,

nobody should feel good about any paper where the evaluation is non-rigorous

In GAN papers we show pretty pictures, but we have absolutely no rigorous way to assess the diversity of samples, or whether any form of overfitting has occurred, at least not as far as I’m aware. I know from experience that getting a sufficiently novel deep learning idea to work is a fragile process: it starts with nothing working, then maybe it starts to work but doesn’t converge, then it converges but to the wrong thing. The whole thing just doesn’t work until it suddenly starts to, and very often it’s unclear what specifically made it work. This process is akin to multiple hypothesis testing. You ran countless experiments and report the result that looks best and behaves the way you expected it to behave. The underlying problem is, we conflate the software development process required to implement a method with manual hyperparameter search and cherry-picking of results. As a result, our reported “empirical evidence” may be more biased and less reliable than one would hope.

you should not resist theory once it becomes available

I agree with Yann that there is merit in starting to adopt techniques before theory or rigorous analysis becomes available. However, once theoretical insight becomes available, reasoning about empirical performance often continues to trump rigour.

Let me tell you about a pattern I encountered a few times (you might say I’m just bitter about this). The pattern: Someone comes up with an idea, they demonstrate it works very well on some large, complicated problem using a very large neural network and loads of tricks and presumably months of manual tweaking and hyper-parameter search. I find a theoretical problem with the method. People say: it still works well in practice, so I don’t see a problem.

This was the kind of response I got to my critique of scheduled sampling and my critique of elastic weight consolidation. In both of these cases reviewers pointed out the methods work just fine on “real-world problems”, and in the case of scheduled sampling people commented “after all the method came first in a benchmark competition so it must be correct”. No, if a method works, but works for the wrong reasons, or for different reasons the authors gave, we have a problem.

You can think of “making a a deep learning method work on a dataset” as a statistical test. I would argue that the statistical power of experiments is very weak. We do a lot of things like early stopping, manual tweaking of hyperparameters, running multiple experiments and only reporting the best results. We probably all know we should not be doing these things when testing hypotheses. Yet, these practices are considered fine when reporting empirical results in ML papers. Many go on and consider these reported empirical results as “strong empirical evidence” in favour of a method.

Summary

I want to thank Ali for giving this talk. Yes, it was confrontational. Insulting? I think provocative is a better word. It was at least somewhat controversial, apparently. It contains a few points I disagree with. But I do not think it was wrong.

It touched upon a lot of problems which I think should be recognized and appreciated by the community. Rigour is not about learning theory, convergence guarantees, bounds or theorem proving. Intellectual rigour applies and can be applied to all of machine learning whether or not we have fully developed mathematical tools for analysis.

Rigour means being thorough, exhaustive, meticulous. It includes good practices like honestly describing the potential weaknesses of a method; thinking about what might go wrong; designing experiments which highlight and analyze these weaknesses; making predictions about your algorithm’s behaviour in certain toy cases and demonstrating empirically that it indeed behaves as expected; refusing to use unjustified evaluation methods; accepting and addressing criticism. All of these should apply to machine learning, deep or not, and indeed they apply to engineering as a whole.