The arithmetic mean of a collection of numbers is simple to calculate. It’s often simply called the average. The formula is shown below:

To find the mean, you sum up all the numbers, then divide by the count of the numbers. Done!

| |If the number of items in the collection is small, it’s not a big deal. However, as the number of items in the collection increases, a potential problem occurs, and this that the sum of all the items gets large. If it gets too large, it might cause an overflow issue. More subtly, loss of precision may occur if there is a large difference in the magnitude of the sum compared to the number of items in the collection (especially when dealing with floating point numbers). Related to this is that you might want to keep a rolling measure of the average. If you have a collection of numbers and know the average, how does the average change with the addition of just one more number?|

|If the number of items in the collection is small, it’s not a big deal. However, as the number of items in the collection increases, a potential problem occurs, and this that the sum of all the items gets large. If it gets too large, it might cause an overflow issue. More subtly, loss of precision may occur if there is a large difference in the magnitude of the sum compared to the number of items in the collection (especially when dealing with floating point numbers). Related to this is that you might want to keep a rolling measure of the average. If you have a collection of numbers and know the average, how does the average change with the addition of just one more number?|

Related to this is that you might want to keep a rolling measure of the average. If you have a collection of numbers and know the average, how does the average change with the addition of just one more number?

To help address these problems, there is a way of calculating the mean using an incremental approach.

Recalling that the formula for the mean is the sum divided by the number of items, we can pull off the most recently added sample out of the sum with no change.

The sum of the n-1 items is the same as the average of these items times multiplied by the number of samples (n-1).

Result!

A little rearrangement gives the useful result of an equation for the mean based entirely on the previous mean, the current sample, and the number of items in the collection. It’s a fairly intuitive looking formula; the new average is the old average simply modified by a normalized component of how much the current sample is different from the past average. This equation is more stable because it avoids the accumulation of, potentially, large sums.

Simple rearrangement gives this additional equation, which we will leverage a little later.

Another incredibly useful statistic metric is the standard deviation (or as I sometimes like to call it “the average deviation from the average”)

Below is the classic formula for standard deviation:

If you use this equation naively, it requires two passes over the data. The first to calculate the mean, then a second to sum the square of the distances from this mean. We can do better.

Squaring (to remove the radicals), converts the standard deviation into the variance, which makes the algebra easier to manipulate!

Multiplying out the squared term results in three sums.

A little bit a rearrangement and cancellation results in the elegant result for variance that does not require intermediate calculation of the mean. All that is needed is to keep track of the cumulative sum of the squares of all the samples, and a cumulative sum of the samples. Nice!

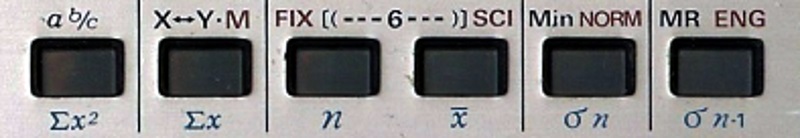

This is how your pocket calculator, in statistics mode, calculates standard deviations (and means). It does not keep track of all the samples you add. Instead, it keeps running totals of just these cumulative sums and the number of items.

As with the arithmetic mean calculation, this approach has issues, namely overflow issues, and precision issues (even worse in this case, as we’re dealing with sums of the squares of the samples).

We can solve these issues by deriving an incremently variance formula.

This is a little more complicated, but we can work through this. To make the equation manipulation a little easier we’ll work with manipulating the product of the variance with the number of samples:

Again, this is a fairly intuitive equation. We can use this result to generate a similar result from n-1 samples instead of n points, and subtract the two of them to find the difference:

Recall back to when we were generating the formula for the incremental mean, we had this result, which we can rearrange.

This nicely substitutes into the incremental variance equation we were working on:

And we are there! We now have an equation Sn in terms of just the previous value, the new data point, and the previous means. From there, it’s easy to divide by the number of samples and square root. This type of algorithm is called an online algorithm.

As this is an incremental formula it does not require the use of a cumulative sum, and so does not suffer from potential overflow issues if the data set gets large.

Related articles

If you enjoyed this article, you might like this which talks about Geometric Means, and how to calculate them in SQL.

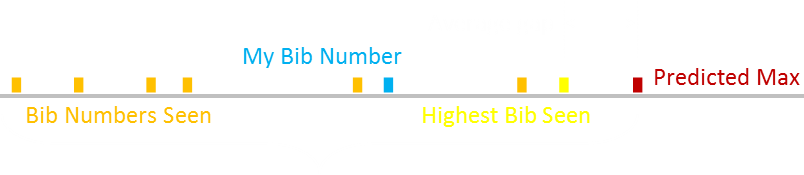

Vaguely related to these incremental approaches is some analysis I did on estimating the size of a marathon race based on bib numbers seen.

(The more bib numbers seen, the more accurate the estimation of the average gap between numbers. This is also called The German Tank Problem).

You can find a complete list of all the articles here. Click here to receive email alerts on new articles.

Click here to receive email alerts on new articles.