Survival of the fittest. <!–

In this post I explain how evolution strategies (ES) work with the aid of a few visual examples. I try to keep the equations light, and I provide links to original articles if the reader wishes to understand more details. This is the first post in a series of articles, where I plan to show how to apply these algorithms to a range of tasks from MNIST, OpenAI Gym, Roboschool to PyBullet environments.

Introduction

Neural network models are highly expressive and flexible, and if we are able to find a suitable set of model parameters, we can use neural nets to solve many challenging problems. Deep learning’s success largely comes from the ability to use the backpropagation algorithm to efficiently calculate the gradient of an objective function over each model parameter. With these gradients, we can efficiently search over the parameter space to find a solution that is often good enough for our neural net to accomplish difficult tasks.

However, there are many problems where the backpropagation algorithm cannot be used. For example, in reinforcement learning (RL) problems, we can also train a neural network to make decisions to perform a sequence of actions to accomplish some task in an environment. However, it is not trivial to estimate the gradient of reward signals given to the agent in the future to an action performed by the agent right now, especially if the reward is realised many timesteps in the future. Even if we are able to calculate accurate gradients, there is also the issue of being stuck in a local optimum, which exists many for RL tasks.

Stuck in a local optimum.

A whole area within RL is devoted to studying this credit-assignment problem, and great progress has been made in recent years. However, credit assignment is still difficult when the reward signals are sparse. In the real world, rewards can be sparse and noisy. Sometimes we are given just a single reward, like a bonus check at the end of the year, and depending on our employer, it may be difficult to figure out exactly why it is so low. For these problems, rather than rely on a very noisy and possibly meaningless gradient estimate of the future to our policy, we might as well just ignore any gradient information, and attempt to use black-box optimisation techniques such as genetic algorithms (GA) or ES.

OpenAI published a paper called Evolution Strategies as a Scalable Alternative to Reinforcement Learning where they showed that evolution strategies, while being less data efficient than RL, offer many benefits. The ability to abandon gradient calculation allows such algorithms to be evaluated more efficiently. It is also easy to distribute the computation for an ES algorithm to thousands of machines for parallel computation. By running the algorithm from scratch many times, they also showed that policies discovered using ES tend to be more diverse compared to policies discovered by RL algorithms.

I would like to point out that even for the problem of identifying a machine learning model, such as designing a neural net’s architecture, is one where we cannot directly compute gradients. While RL, Evolution, GA etc., can be applied to search in the space of model architectures, in this post, I will focus only on applying these algorithms to search for parameters of a pre-defined model.

What is an Evolution Strategy?

The diagrams below are top-down plots of shifted 2D Schaffer and Rastrigin functions, two of several simple toy problems used for testing continuous black-box optimisation algorithms. Lighter regions of the plots represent higher values of . As you can see, there are many local optimums in this function. Our job is to find a set of model parameters , such that is as close as possible to the global maximum.

Although there are many definitions of evolution strategies, we can define an evolution strategy as an algorithm that provides the user a set of candidate solutions to evaluate a problem. The evaluation is based on an objective function that takes a given solution and returns a single fitness value. Based on the fitness results of the current solutions, the algorithm will then produce the next generation of candidate solutions that is more likely to produce even better results than the current generation. The iterative process will stop once the best known solution is satisfactory for the user.

Given an evolution strategy algorithm called EvolutionStrategy, we can use in the following way:

solver = EvolutionStrategy()

while True:

# ask the ES to give us a set of candidate solutions solutions = solver.ask()

# create an array to hold the fitness results. fitness_list = np.zeros(solver.popsize)

# evaluate the fitness for each given solution. for i in range(solver.popsize): fitness_list[i] = evaluate(solutions[i])

# give list of fitness results back to ES solver.tell(fitness_list)

# get best parameter, fitness from ES best_solution, best_fitness = solver.result()

if best_fitness > MY_REQUIRED_FITNESS: break

Although the size of the population is usually held constant for each generation, they don’t need to be. The ES can generate as many candidate solutions as we want, because the solutions produced by an ES are sampled from a distribution whose parameters are being updated by the ES at each generation. I will explain this sampling process with an example of a simple evolution strategy.

Simple Evolution Strategy

One of the simplest evolution strategy we can imagine will just sample a set of solutions from a Normal distribution, with a mean and a fixed standard deviation . In our 2D problem, and . Initially, is set at the origin. After the fitness results are evaluated, we set to the best solution in the population, and sample the next generation of solutions around this new mean. This is how the algorithm behaves over 20 generations on the two problems mentioned earlier:

In the visualisation above, the green dot indicates the mean of the distribution at each generation, the blue dots are the sampled solutions, and the red dot is the best solution found so far by our algorithm.

This simple algorithm will generally only work for simple problems. Given its greedy nature, it throws away all but the best solution, and can be prone to be stuck at a local optimum for more complicated problems. It would be beneficial to sample the next generation from a probability distribution that represents a more diverse set of ideas, rather than just from the best solution from the current generation.

Simple Genetic Algorithm

One of the oldest black-box optimisation algorithms is the genetic algorithm. There are many variations with many degrees of sophistication, but I will illustrate the simplest version here.

The idea is quite simple: keep only 10% of the best performing solutions in the current generation, and let the rest of the population die. In the next generation, to sample a new solution is to randomly select two solutions from the survivors of the previous generation, and recombine their parameters to form a new solution. This crossover recombination process uses a coin toss to determine which parent to take each parameter from. In the case of our 2D toy function, our new solution might inherit or from either parents with 50% chance. Gaussian noise with a fixed standard deviation will also be injected into each new solution after this recombination process.

The figure above illustrates how the simple genetic algorithm works. The green dots represent members of the elite population from the previous generation, the blue dots are the offsprings to form the set of candidate solutions, and the red dot is the best solution.

Genetic algorithms help diversity by keeping track of a diverse set of candidate solutions to reproduce the next generation. However, in practice, most of the solutions in the elite surviving population tend to converge to a local optimum over time. There are more sophisticated variations of GA out there, such as CoSyNe, ESP, and NEAT, where the idea is to cluster similar solutions in the population together into different species, to maintain better diversity over time.

Covariance-Matrix Adaptation Evolution Strategy (CMA-ES)

A shortcoming of both the Simple ES and Simple GA is that our standard deviation noise parameter is fixed. There are times when we want to explore more and increase the standard deviation of our search space, and there are times when we are confident we are close to a good optima and just want to fine tune the solution. We basically want our search process to behave like this:

Amazing isn’it it? The search process shown in the figure above is produced by Covariance-Matrix Adaptation Evolution Strategy (CMA-ES). CMA-ES an algorithm that can take the results of each generation, and adaptively increase or decrease the search space for the next generation. It will not only adapt for the mean and sigma parameters, but will calculate the entire covariance matrix of the parameter space. At each generation, CMA-ES provides the parameters of a multi-variate normal distribution to sample solutions from. So how does it know how to increase or decrease the search space?

Before we discuss its methodology, let’s review how to estimate a covariance matrix. This will be important to understand CMA-ES’s methodology later on. If we want to estimate the covariance matrix of our entire sampled population of size of , we can do so using the set of equations below to calculate the maximum likelihood estimate of a covariance matrix . We first calculate the means of each of the and in our population:

The terms of the 2x2 covariance matrix will be:

Of course, these resulting mean estimates and , and covariance terms , , will just be an estimate to the actual covariance matrix that we originally sampled from, and not particularly useful to us.

CMA-ES modifies the above covariance calculation formula in a clever way to make it adapt well to an optimisation problem. I will go over how it does this step-by-step. Firstly, it focuses on the best solutions in the current generation. For simplicity let’s set to be the best 25% of solutions. After sorting the solutions based on fitness, we calculate the mean of the next generation as the average of only the best 25% of the solutions in current population , i.e.:

Next, we use only the best 25% of the solutions to estimate the covariance matrix of the next generation, but the clever hack here is that it uses the current generation’s , rather than the updated parameters that we had just calculated, in the calculation:

Armed with a set of , , , , and parameters for the next generation , we can now sample the next generation of candidate solutions.

Below is a set of figures to visually illustrate how it uses the results from the current generation to construct the solutions in the next generation :

-

Calculate the fitness score of each candidate solution in generation .

-

Isolates the best 25% of the population in generation , in purple.

-

Using only the best solutions, along with the mean of the current generation (the green dot), calculate the covariance matrix of the next generation.

-

Sample a new set of candidate solutions using the updated mean and covariance matrix .

Let’s visualise the scheme one more time, on the entire search process on both problems:

Because CMA-ES can adapt both its mean and covariance matrix using information from the best solutions, it can decide to cast a wider net when the best solutions are far away, or narrow the search space when the best solutions are close by. My description of the CMA-ES algorithm for a 2D toy problem is highly simplified to get the idea across. For more details, I suggest reading the CMA-ES Tutorial prepared by Nikolaus Hansen, the author of CMA-ES.

This algorithm is one of the most popular gradient-free optimisation algorithms out there, and has been the algorithm of choice for many researchers and practitioners alike. The only real drawback is the performance if the number of model parameters we need to solve for is large, as the covariance calculation is , although recently there has been approximations to make it . CMA-ES is my algorithm of choice when the search space is less than a thousand parameters. I found it still usable up to ~ 10K parameters if I’m willing to be patient.

Natural Evolution Strategies

Imagine if you had built an artificial life simulator, and you sample a different neural network to control the behavior of each ant inside an ant colony. Using the Simple Evolution Strategy for this task will optimise for traits and behaviours that benefit individual ants, and with each successive generation, our population will be full of alpha ants who only care about their own well-being.

Instead of using a rule that is based on the survival of the fittest ants, what if you take an alternative approach where you take the sum of all fitness values of the entire ant population, and optimise for this sum instead to maximise the well-being of the entire ant population over successive generations? Well, you would end up creating a Marxist utopia.

A perceived weakness of the algorithms mentioned so far is that they discard the majority of the solutions and only keep the best solutions. Weak solutions contain information about what not to do, and this is valuable information to calculate a better estimate for the next generation.

Many people who studied RL are familiar with the REINFORCE paper. In this 1992 paper, Williams outlined an approach to estimate the gradient of the expected rewards with respect to the model parameters of a policy neural network. This paper also proposed using REINFORCE as an Evolution Strategy, in Section 6 of the paper. This special case of REINFORCE-ES was expanded later on in Parameter-Exploring Policy Gradients (PEPG, 2009) and Natural Evolution Strategies (NES, 2014).

In this approach, we want to use all of the information from each member of the population, good or bad, for estimating a gradient signal that can move the entire population to a better direction in the next generation. Since we are estimating a gradient, we can also use this gradient in a standard SGD update rule typically used for deep learning. We can even use this estimated gradient with Momentum SGD, RMSProp, or Adam if we want to.

The idea is to maximise the expected value of the fitness score of a sampled solution. If the expected result is good enough, then the best performing member within a sampled population will be even better, so optimising for the expectation might be a sensible approach. Maximising the expected fitness score of a sampled solution is almost the same as maximising the total fitness score of the entire population.

If is a solution vector sampled from a probability distribution function , we can define the expected value of the objective function as:

where are the parameters of the probability distribution function. For example, if is a normal distribution, then would be and . For our simple 2D toy problems, each ensemble is a 2D vector .

The NES paper contains a nice derivation of the gradient of with respect to . Using the same log-likelihood trick as in the REINFORCE algorithm allows us to calculate the gradient of :

In a population size of , where we have solutions , , , we can estimate this gradient as a summation:

With this gradient , we can use a learning rate parameter (such as 0.01) and start optimising the parameters of pdf so that our sampled solutions will likely get higher fitness scores on the objective function . Using SGD (or Adam), we can update for the next generation:

and sample a new set of candidate solutions from this updated pdf, and continue until we arrive at a satisfactory solution.

In Section 6 of the REINFORCE paper, Williams derived closed-form formulas of the gradient , for the special case where is a factored multi-variate normal distribution (i.e., the correlation parameters are zero). In this special case, are the and vectors. Therefore, each element of a solution can be sampled from a univariate normal distribution .

The closed-form formulas for , for each individual element of vector on each solution in the population can be derived as:

For clarity, I use the index of , to count across parameter space, and this is not to be confused with superscript , used to count across each sampled member of the population. For our 2D problems, , , , , , in this context.

These two formulas can be plugged back into the approximate gradient formula to derive explicit update rules for and . In the papers mentioned above, they derived more explicit update rules, incorporated a baseline, and introduced other tricks such as antithetic sampling in PEPG, which is what my implementation is based on. NES proposed incorporating the inverse of the Fisher Information Matrix into the gradient update rule. But the concept is basically the same as other ES algorithms, where we update the mean and standard deviation of a multi-variate normal distribution at each new generation, and sample a new set of solutions from the updated distribution. Below is a visualization of this algorithm in action, following the formulas described above:

We see that this algorithm is able to dynamically change the ’s to explore or fine tune the solution space as needed. Unlike CMA-ES, there is no correlation structure in our implementation, so we don’t get the diagonal ellipse samples, only the vertical or horizontal ones, although in principle we can derive update rules to incorporate the entire covariance matrix if we needed to, at the expense of computational efficiency.

I like this algorithm because like CMA-ES, the ’s can adapt so our search space can be expanded or narrowed over time. Because the correlation parameter is not used in this implementation, the efficiency of the algorithm is so I use PEPG if the performance of CMA-ES becomes an issue. I usually use PEPG when the number of model parameters exceed several thousand.

OpenAI Evolution Strategy

In OpenAI’s paper, they implement an evolution strategy that is a special case of the REINFORCE-ES algorithm outlined earlier. In particular, is fixed to a constant number, and only the parameter is updated at each generation. Below is how this strategy looks like, with a constant parameter:

In addition to the simplification, this paper also proposed a modification of the update rule that is suitable for parallel computation across different worker machines. In their update rule, a large grid of random numbers have been pre-computed using a fixed seed. By doing this, each worker can reproduce the parameters of every other worker over time, and each worker needs only to communicate a single number, the final fitness result, to all of the other workers. This is important if we want to scale evolution strategies to thousands or even a million workers located on different machines, since while it may not be feasible to transmit an entire solution vector a million times at each generation update, it may be feasible to transmit only the final fitness results. In the paper, they showed that by using 1440 workers on Amazon EC2 they were able to solve the Mujoco Humanoid walking task in ~ 10 minutes.

I think in principle, this parallel update rule should work with the original algorithm where they can also adapt , but perhaps in practice, they wanted to keep the number of moving parts to a minimum for large-scale parallel computing experiments. This inspiring paper also discussed many other practical aspects of deploying ES for RL-style tasks, and I highly recommend going through it to learn more.

Fitness Shaping

Most of the algorithms above are usually combined with a fitness shaping method, such as the rank-based fitness shaping method I will discuss here. Fitness shaping allows us to avoid outliers in the population from dominating the approximate gradient calculation mentioned earlier:

If a particular is much larger than other in the population, then the gradient might become dominated by this outliers and increase the chance of the algorithm being stuck in a local optimum. To mitigate this, one can apply a rank transformation of the fitness. Rather than use the actual fitness function, we would rank the results and use an augmented fitness function which is proportional to the solution’s rank in the population. Below is a comparison of what the original set of fitness may look like, and what the ranked fitness looks like:

What this means is supposed we have a population size of 101. We would evaluate each population to the actual fitness function, and then sort the solutions based by their fitness. We will assign an augmented fitness value of -0.50 to the worse performer, -0.49 to the second worse solution, …, 0.49 to the second best solution, and finally a fitness value of 0.50 to the best solution. This augmented set of fitness values will be used to calculate the gradient update, instead of the actual fitness values. In a way, it is a similar to just applying Batch Normalization to the results, but more direct. There are alternative methods for fitness shaping but they all basically give similar results in the end.

I find fitness shaping to be very useful for RL tasks if the objective function is non-deterministic for a given policy network, which is often the cases on RL environments where maps are randomly generated and various opponents have random policies. It is less useful for optimising for well-behaved functions that are deterministic, and the use of fitness shaping can sometimes slow down the time it takes to find a good solution.

MNIST

Although ES might be a way to search for more novel solutions that are difficult for gradient-based methods to find, it still vastly underperforms gradient-based methods on many problems where we can calculate high quality gradients. For instance, only an idiot would attempt to use a genetic algorithm for image classification. But sometimes such people do exist in the world, and sometimes these explorations can be fruitful!

Since all ML algorithms should be tested on MNIST, I also tried to apply these various ES algorithms to find weights for a small, simple 2-layer convnet used to classify MNIST, just to see where we stand compared to SGD. The convnet only has ~ 11k parameters so we can accommodate the slower CMA-ES algorithm. The code and the experiments are available here.

Below are the results for various ES methods, using a population size of 101, over 300 epochs. We keep track of the model parameters that performed best on the entire training set at the end of each epoch, and evaluate this model once on the test set after 300 epochs. It is interesting how sometimes the test set’s accuracy is higher than the training set for the models that have lower scores.

|Method|Train Set|Test Set

|——

|Adam (BackProp) Baseline|99.8|98.9|

|Simple GA|82.1|82.4|

|CMA-ES|98.4|98.1|

|OpenAI-ES|96.0|96.2|

|PEPG|98.5|98.0|

We should take these results with a grain of salt, since they are based on a single run, rather than the average of 5-10 runs. The results based on a single-run seem to indicate that CMA-ES is the best at the MNIST task, but the PEPG algorithm is not that far off. Both of these algorithms achieved ~ 98% test accuracy, 1% lower than the SGD/ADAM baseline. Perhaps the ability to dynamically alter its covariance matrix, and standard deviation parameters over each generation allowed it to fine-tune its weights better than OpenAI’s simpler variation.

Try It Yourself

There are probably open source implementations of all of the algorithms described in this article. The author of CMA-ES, Nikolaus Hansen, has been maintaining a numpy-based implementation of CMA-ES with lots of bells and whistles. His python implementation introduced me to the training loop interface described earlier. Since this interface is quite easy to use, I also implemented the other algorithms such as Simple Genetic Algorithm, PEPG, and OpenAI’s ES using the same interface, and put it in a small python file called es.py, and also wrapped the original CMA-ES library in this small library. This way, I can quickly compare different ES algorithms by just changing one line:

import es

#solver = es.SimpleGA(...)#solver = es.PEPG(...)#solver = es.OpenES(...)solver = es.CMAES(...)

while True:

solutions = solver.ask()

fitness_list = np.zeros(solver.popsize)

for i in range(solver.popsize): fitness_list[i] = evaluate(solutions[i])

solver.tell(fitness_list)

result = solver.result()

if result[1] > MY_REQUIRED_FITNESS: break

You can look at es.py on GitHub and the IPython notebook examples using the various ES algorithms.

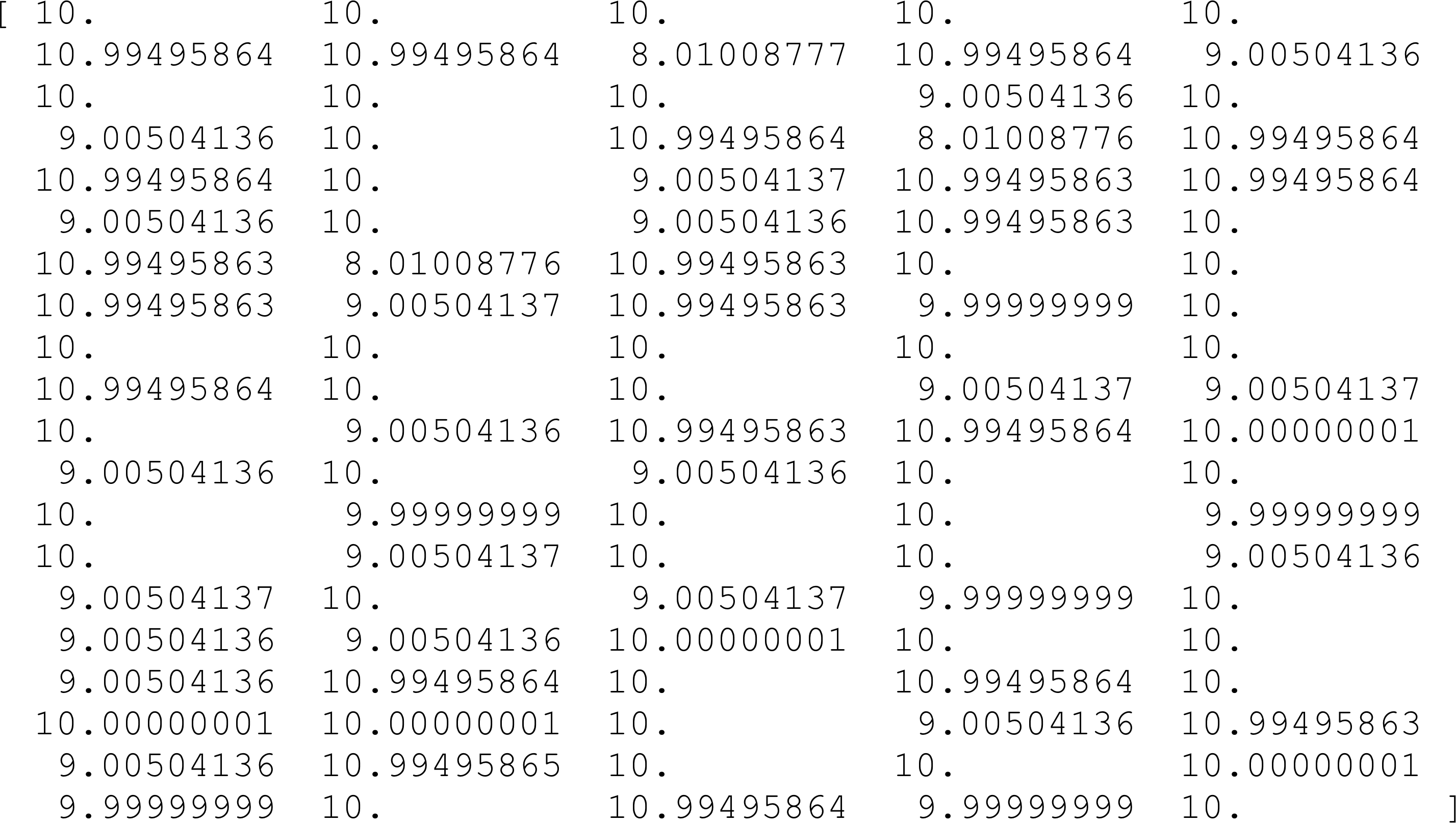

In this IPython notebook that accompanies es.py, I show how to use the ES solvers in es.py to solve a 100-Dimensional version of the Rastrigin function with even more local optimum points. The 100-D version is somewhat more challenging than the trivial 2D version used to produce the visualizations in this article. Below is a comparison of the performance for various algorithms discussed:

On this 100-D Rastrigin problem, none of the optimisers got to the global optimum solution, although CMA-ES comes close. CMA-ES blows everything else away. PEPG is in 2nd place, and OpenAI-ES / Genetic Algorithm falls behind. I had to use an annealing schedule to gradually lower for OpenAI-ES to make it perform better for this task.

What’s Next?

In the next article, I will look at applying ES to other experiments and more interesting problems. Please check it out!

References and Other Links

Below are a few links to information related to evolutionary computing which I found useful or inspiring.

Image Credits of Lemmings Jumping off a Cliff. Your results may vary when investing in ICOs.

CMA-ES: Official Reference Implementation on GitHub, Tutorial, Original CMA-ES Paper from 2001, Overview Slides

Simple Statistical Gradient-Following Algorithms for Connectionist Reinforcement Learning (REINFORCE), 1992.

Parameter-Exploring Policy Gradients, 2009.

Natural Evolution Strategies, 2014.

Evolution Strategies as a Scalable Alternative to Reinforcement Learning, OpenAI, 2017.

Risto Miikkulainen’s Slides on Neuroevolution.

A Neuroevolution Approach to General Atari Game Playing, 2013.

Kenneth Stanley’s Talk on Why Greatness Cannot Be Planned: The Myth of the Objective, 2015.

Neuroevolution: A Different Kind of Deep Learning. The quest to evolve neural networks through evolutionary algorithms.

Compressed Network Search Finds Complex Neural Controllers with a Million Weights.

Karl Sims Evolved Virtual Creatures, 1994.

Evolved Step Climbing Creatures.

Super Mario World Agent Mario I/O, Mario Kart 64 Controller using using NEAT Algorithm.

Ingo Rechenberg, the inventor of Evolution Strategies.

A Tutorial on Differential Evolution with Python.

My Previous Evolutionary Projects

PathNet: Evolution Channels Gradient Descent in Super Neural Networks

Neural Network Evolution Playground with Backprop NEAT

Evolved Neural Art Gallery using CPPN Implementation

Creatures Avoiding Planks

Neural Slime Volleyball

Evolution of Inverted Double Pendulum Swing Up Controller