Welcome to part 2 of the JackBlockChain, where I write some code to introduce the ability for different nodes to communicate.

Initially my goal was to write about nodes syncing up and talking with each other, along with mining and broadcasting their winning blocks to other nodes. In the end, I realized that the amount of code and explanation to accomplish all of that was way too big for one post. Because of this, I decided to make part 2 only about nodes beginning the process of talking for the future.

By reading this you’ll get a sense of what I did and how I did it. But you won’t be seeing all the code. There’s so much code involved that if you’re looking for my total implementation you should look at the entire code on the part-2 branch on Github.

Like all programming, I didn’t write the following code in order. I had different ideas, tried different tactics, deleted some code, wrote some more, deleted that code, and then ended up with the following.

This is totally fine! I wanted to mention my process so people reading this don’t always think that someone who writes about programming does it in the sequence they write about it. If it were easy to do, I’d really like to write about different things I tried, bugs I had that weren’t simple to fix, parts where I was stuck and didn’t easily know how to move forward.

It’s difficult to explain the full process and I assume most people reading this aren’t looking to know how people program, they want to see the code and implementation. Just keep in mind that programming is very rarely in a sequence.

Twitter, contact, and feel free to use comments below to yell at me, tell me what I did wrong, or tell me how helpful this was. Big fan of feedback.

Other Posts in This Series

TL;DR

If you’re looking to learn about how blockchain mining works, you’re not going to learn it here. For now, read part 1 where I talk about it initially, and wait for more parts of this project where I go into more advanced mining.

At the end, I’ll show the way to create nodes which, when running, will ask other nodes what blockchain they’re using, and be able to store it locally to be used when they start mining. That’s it. Why is this post so long? Because there is so much involved in building up the code to make it easier to work with for this application and for the future.

That being said, the syncing here isn’t super advanced. I go over improving the classes involved in the chain, testing the new features, creating other nodes simply, and finally a way for nodes to sync when they start running.

For these sections, I talk about the code and then paste the code, so get ready.

Expanding Block and adding Chain class

This project is a great example of the benefits of Object Oriented Programming. In this section, I’m going to start talking about the changes to the Block class, and then go in to the creation of the Chain class.

The big keys for Blocks are:

-

Throwing in a way to convert the keys in the Block’s header from input values to the types we’re looking for. This makes it easy to dump in a json dict from a file and convert the string value of the index, nonce, and second timestamp into ints. This could change in the future for new variables. For example if I want to convert the datetime into an actual datetime object, this method will be good to have.

-

Validating the block by checking whether the hash begins with the required number of zeros.

-

The ability for the block to save itself in the chaindata folder. Allowing this rather than requiring a utility function to take care of that.

Overriding some of the operator functions.

-

repr for making it easier to get quick information about the block when debugging. It overrides str as well if you’re printing.

-

eq that allows you to compare two blocks to see if they’re equal with

==. Otherwise Python will compare with the address the block has in memory. We’re looking for data comparison -

ne, opposite of eq of course

-

In the future, we’ll probably want to have some greater than (gt) operator so we’d be able to simply use > to see which chain is better. But right now, we don’t have a good way to do that.

Again, these operations can easily change in the future.

Chain time.

-

Initialize a Chain by passing in a list of blocks.

Chain([block_zero, block_one])orChain([])if you’re creating an empty chain. -

Validity is determined by index incrementing by one, prev_hash is actually the hash of the previous block, and hashes have valid zeros.

-

The ability to save the block to chaindata

-

The ability to find a specific block in the chain by index or by hash

-

The length of the chain, which can be called by

len(chain_obj)is the length of self.blocks -

Equality of chains requires list of blocks of equal lengths that are all equal.

-

Greater than, less than are determined only by the length of the chain

-

Ability to add a block to the chain, currently by throwing it on the end of the

blockvariable, not checking validitiy -

Returning a list of dictionary objects for all the blocks in the chain.

Woof. Ok fine, I listed a lot of the functions of the Chain class here. In the future, these functions are probably going to change, most notably the gt and lt comparisons. Right now, this handles a bunch of abilities we’re looking for.

Testing

I’m going to throw my note about testing the classes here. I have the ability to mine new blocks which use the classes. One way to test is to change the classes, run the mining, observe the errors, try to fix, and then run the mining again. That’s quite a waste of time in that testing all parts of the code would take forever, especially when .

There are a bunch of testing libraries out there, but they do involve a bunch of formatting. I don’t want to take that on right now, so having a test.py definitely works.

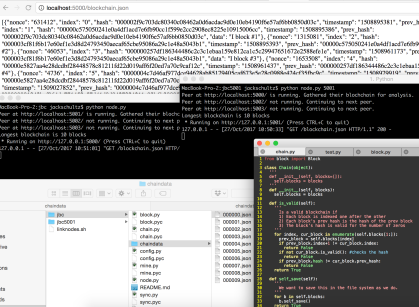

In order to get the block dicts listed at the start, I simply ran the mining algorithm a few times to get a valid chain of the block dicts. From there, I write sections that test the different parts of the classes. If I change or add something to the classes, it barely takes any time to write the test for it. When I run python test.py, the file runs incredibly quickly and tells me exactly which line the error was from.

Future additions to test.py include using one of the fancy testing libraries which will run all the tests separately. This would let you know all of the tests that could fail rather than dealing with them one at a time. Another would be to put the test block dicts in files instead of in the script. For example, adding a chaindata dir in the test dir so I can test the creation and saving of blocks.

Peers, and Hard Links

The whole point of this part of the jbc is to be able to create different nodes that can run their own mining, own nodes on different ports, store their own chains to their own chaindata folder, and have the ability to give other peers their blockchain.

To do this, I want to share the files quickly between the folders so any change to one will be represented in the other blockchain nodes. Enter hard links.

At first I tried rsync, where I would run the bash script and have it copy the main files into a different local folder. The problem with this is that every change to a file and restart of the node would require me to ship the files over. I don’t want to have to do that all the time.

Hard links, on the other hand, will make the OS point the files in the different folder exactly to the files in my main jbc folder. Any change and save for the main files will be represented in the other nodes.

Here’s the bash script I created that will link the folders.

To run, $./linknodes 5001 to create a folder called jbc5001 with the correct files.

Since Flask runs initially on port 5000, I’m gong to use 5001, 5002, and 5003 as my initial peer nodes. Define them in config.py and use them when config is imported. As with many parts of the code, this will definitely change to make sure peers aren’t hardcoded. We want to be able to ask for new ones.

Cool. In part 1, the Flask node already has an endpoint for sharing it’s blockchain so we’re good on that front, but we still need to write the code to ask our peer friends about what they’re working with.

Quick side, we’re using Flask and http. This works in our case, but a blockchain like Ethereum has their own protocol for broadcasting, the Ethereum Wire Protocol.

Syncing

When a node or mine starts, the first requirement is to sync up to get a valid blockchain to work from. There are two parts to this – first, getting that node’s local blockchain it has in its (fix the it’s to be its) chaindata dtr, and second, the ability to ask your peers what they have.

There’s a big part of syncing that I’m ignoring for now — determining which chain is the best to work with. Remember back in the gt method in the Chain class? All I’m doing is seeing which chain is longer than the other. That’s not going to cut it when we’re dealing with information being locked in and unchangeable.

Imagine if a node starts mining on its own, goes off in a different direction and doesn’t ask peers what they’re working on, gets lucky to create new valid blocks with its own data, and ends up longer than the others but wayy different blocks. Should they be considered to have the most valid and correct block? Right now, I’m going to stick with length. This’ll change in a future part of this project.

Another part of the code below to keep in mind is how few error checks I have. I’m assuming the files and block dicts are valid without any attempted changes. Important for production and wider distribution, but not for now.

Foreward: sync_local() is pretty much the same as the initial sync_local() from part 1 so I’m not going to include the difference here. The new sync_overall.py asks peers what they have for the blockchains and determines the best by chain length.

Now when we run node.py we want to sync the blockchain we’re going to use. This involves initially asking peers what they’re woking with and saving the best. Then when we get asked about our own blockchain we’ll use the local-saved chain. node.py requires a couple changes. Also see how much simpler the blockchain function is than from part 1? That’s why classes are great to use.

Testing time! We want to do the following to show that our nodes are syncing up.

-

Create an initial generation and main node where we mine something like 6 blocks.

-

Hard link the files to create a new folder with a node for a different port.

-

Run

node.pyfor the secondary node and view theblockchain.jsonendpoint to see that we don’t have any blocks for now. -

Run the main node.

-

Shutdown and restart the secondary node.

-

Check to see if the secondary node’s chaindata dir has the block json files, and see that its /blockchain.json enpoint is now showing the same chain as the main node.

I suppose I could share screenshots of this, or create a video that depicts me going through the process, but you can believe me or take the git repo and try this yourself. Did I mention that programming > only reading?

That’s it, for now

As you read above and as you read from reading this post all the way to the bottom, I didn’t talk about syncing with other nodes after mining. That’ll be Part 3. And then after Part 3 there’s still a bunch to go. Things like creating a Header class that advances the information and structure of the header rather than only having the Block object.

How about the bigger and more correct logic behind determining what the correct blockchain is when you sync up? Huge part I haven’t addressed yet.

Another big part would be syncing data transactions. Right now all we have are dumb little sentences for data that tell people what index the block is. We need to be able to distribute data and tell other nodes what to include in the block.

Tons to go, but we’re on our way. Again, twitter, contact, github repo for Part 2 branch. Catch y’all next time.

Like this:

Like Loading…

Related