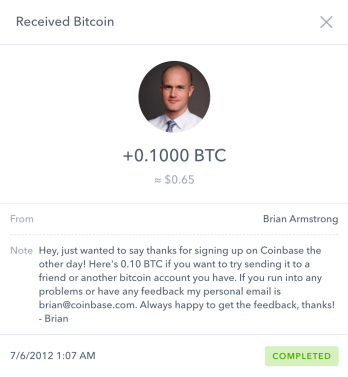

I can actually look up how long I have by logging into my Coinbase account, looking at the history of the Bitcoin wallet, and seeing this transaction I got back in 2012 after signing up for Coinbase. Bitcoin was trading at about $6.50 per. If I still had that 0.1 BTC, that’d be worth over $500 at the time of this writing. In case people are wondering, I ended up selling that when a Bitcoin was worth $2000. So I only made $200 out of it rather than the $550 now. Should have held on.

Thank you Brian.

Despite knowing about Bitcoin’s existence, I never got much involved. I saw the rises and falls of the $/BTC ratio. I’ve seen people talk about how much of the future it is, and seen a few articles about how pointless BTC is. I never had an opinion on that, only somewhat followed along.

Similarly, I have barely followed blockchains themselves. Recently, my dad has brought up multiple times how the CNBC and Bloomberg stations he watches in the mornings bring up blockchains often, and he doesn’t know what it means at all.

And then suddenly, I figured I should try to learn about the blockchain more than the top level information I had. I started by doing a lot of “research”, which means I would search all around the internet trying to find other articles explaining the blockchain. Some were good, some were bad, some were dense, some were super upper level.

Reading only goes so far, and if there’s one thing I know, it’s that reading to learn doesn’t get you even close to the knowledge you get from programming to learn. So I figured I should go through and try to write my own basic local blockchain.

A big thing to mention here is that there are differences in a basic blockchain like I’m describing here and a ‘professional’ blockchain. This chain will not create a crypto currency. Blockchains do not require producing coins that can be traded and exchanged for physical money. Blockchains are used to store and verify information. Coins help incentive nodes to participate in validation but don’t need to exist.

The reason I’m writing this post is 1) so people reading this can learn more about blockchains themselves, and 2) so I can try to learn more by explaining the code and not just writing it.

In this post, I’ll show the way I want to store the blockchain data and generate an initial block, how a node can sync up with the local blockchain data, how to display the blockchain (which will be used in the future to sync with other nodes), and then how to go through and mine and create valid new blocks. For this first post, there are no other nodes. There are no wallets, no peers, no important data. Information on those will come later.

Other Posts in This Series

TL;DR

If you don’t want to get into specifics and read the code, or if you came across this post while searching for an article that describes blockchains understandably, I’ll attempt to write a summary about how a blockchains work.

At a super high level, a blockchain is a database where everyone participating in the blockchain is able to store, view, confirm, and never delete the data.

On a somewhat lower level, the data in these blocks can be anything as long as that specific blockchain allows it. For example, the data in the Bitcoin blockchain is only transactions of Bitcoins between accounts. The Ethereum blockchain allows similar transactions of Ether’s, but also transactions that are used to run code.

Slightly more downward, before a block is created and linked into the blockchain, it is validated by a majority of people working on the blockchain, referred to as nodes. The true blockchain is the chain containing the greatest number of blocks that is correctly verified by the majority of the nodes. That means if a node attempts to change the data in a previous block, the newer blocks will not be valid and nodes will not trust the data from the incorrect block.

Don’t worry if this is all confusing. It took me a while to figure that out myself and a much longer time to be able to write this in a way that my sister (who has no background in anything blockchain) understands.

If you want to look at the code, check out the part 1 branch on Github. Anyone with questions, comments, corrections, or praise (if you feel like being super nice!), get in contact, or let me know on twitter.

Step 1 — Classes and Files

Step 1 for me is to write a class that handles the blocks when a node is running. I’ll call this class Block. Frankly, there isn’t much to do with this class. In the __init__ function, we’re going to trust that all the required information is provided in a dictionary. If I were writing a production blockchain, this wouldn’t be smart, but it’s fine for the example where I’m the only one writing all the code. I also want to write a method that spits out the important block information into a dict, and then have a nicer way to show block information if I print a block to the terminal.

When we’re looking to create a first block, we can run the simple code.

Nice. The final question of this section is where to store the data in the file system. We want this so we don’t lose our local block data if we turn off the node.

In an attempt to somewhat copy the Etherium Mist folder scheme, I’m going to name the folder with the data ‘chaindata’. Each block will be allowed its own file for now where it’s named based on its index. We need to make sure that the filename begins with plenty of leading zeros so the blocks are in numerical order.

With the code above, this is what I need to create the first block.

Step 2 — Syncing the blockchain, locally

When you start a node, before you’re able to start mining, interpreting the data, or send / create new data for the chain, you need to sync the node. Since there are no other nodes, I’m only talking about reading the blocks from the local files. In the future, reading from files will be part of syncing, but also talking to peers to gather the blocks that were generated while you weren’t running your own node.

Nice and simple, for now. Reading strings from a folder and loading them into data structures doesn’t require super complicated code. For now this works. But in future posts when I write the ability for different nodes to communicate, this sync function is going to get a lot more complicated.

Step 3 — Displaying the blockchain

Now that we have the blockchain in memory, I want to start being able to show the chain in a browser. Two reasons for doing this now. First is to validate in a browser that things have changed. And then also I’ll want to use the browser in the future to view and act on the blockchain. Like sending transactions or managing wallets.

I use Flask here since it’s impressively easy to start, and also since I’m in control.

Here’s the code to show the blockchain json. I’ll ignore the import requirements to save space here.

Run this code, visit localhost:3000/blockchain.json, and you’ll see the current blocks spit out.

Part 4 — “Mining”, also known as block creation

We only have that one genesis block, and if we have more data we want to store and distribute, we need a way to include that into a new block. The question is how to create a new block while linking back to a previous one.

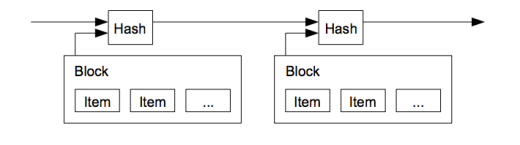

In the Bitcoin whitepaper, Satoshi describes it as the following. Note that ‘timestamp server’ is referred to as a ‘node’:

The solution we propose begins with a timestamp server. A timestamp server works by taking a hash of a block of items to be timestamped and widely publishing the hash… The timestamp proves that the data must have existed at the time, obviously, in order to get into the hash. Each timestamp includes the previous timestamp in its hash, forming a chain, with each additional timestamp reinforcing the ones before it.

Here’s a screenshot of the picture below the description.

A summary of that section is that in order to link the blocks together, we create a hash of the information of a new block that includes the time of block creation, the hash of the previous block, and the information in the block. I’ll refer to this group of information as the block’s ‘header’. In this way, we’re able to verify a block’s truthfulness by running through all the hashes before a block and validating the sequence.

For my header the case here the header I’m creating is adding the string values together into a giant string. The data I’m including is:

-

Index, meaning which number of block this will be

-

Previous block’s hash

-

the data, in this case is just random strings. For bitcoin, this is referred to as the Merkle root, which is info about the transactions

-

The timestamp of when we’re mining the block

Before getting confused, adding the strings of information together isn’t required to create a header. The requirementis that everyone knows how to generate a block’s header, and within the header is the previous block’s hash.This is so everyone can confirm the correct hash for the new block, and validate the link between the two blocks.

The Bitcoin header is much more complex than combining strings. It uses hashes of data, times, and deals with how the bytes are stored in computer memory. But for now, adding strings suffices.

Once we have the header, we want to go through and calculate the validated hash, and by calculating the hash. In my hash calculation, I’m going to be doing something slightly different than Bitcoin’s method, but I’m still running the block header through the sha256 function.

Finally, to mine the block we use the functions above to get a hash for the new block, store the hash in the new block, and then save that block to the chaindata directory.

Tada! Though with this type of block creation, whoever has the fastest CPU is able to create a chain that’s the longest which other nodes would conceive as true. We need some way to slow down block creation and confirm each other before moving towards the next block.

Part 5 — Proof-of-Work

In order to do the slowdown, I’m throwing in Proof-of-Work as Bitcoin does. Proof-of-Stake is another way you’ll see blockchains use to get consensus, but for this I’ll go with work.

The way to do this is to adjust the requirement that a block’s hash has certain properties. Like bitcoin, I’m going to make sure that the hash begins with a certain number of zeros before you can move on to the next one. The way to do this is to throw on one more piece of information into the header — a nonce.

Now the mining function is adjusted to create the hash, but if the block’s hash doesn’t lead with enough zeros, we increment the nonce value, create the new header, calculate the new hash and check to see if that leads with enough zeros.

Excellent. This new block contains the valid nonce value so other nodes can validate the hash. We can generate, save, and distribute this new block to the rest.

Summary

And that’s it! For now. There are tons of questions and features for this blockchain that I haven’t included.

For example, how do other nodes become involved? How would nodes transfer data that they want included in a block? How do we store the information in the block other than just a giant string Is there a better type of header that doesn’t include that giant data string?

There will be more parts of the series coming where I’ll move forward with solving these questions. So if you have suggestions of what parts you want to see, let me know on twitter, comment on this post, or get in contact!

Thanks to my sister Sara for reading through this for edits, and asking questions about blockchains so I had to rewrite to clarify.

Like this:

Like Loading…

Related