So you know the Cheshire cat, yeah? Ever wonder what it’s point is? Like, it turns up in a number of places, but does it foreshadow or emphasize plot turns? Might it signify coming improvements or declines?

In my last post I confirmed that plot arcs from smoothed word sentiments seem to provide sensible representations of the plot progressions. Here, I’d like to try answering the questions about the Cheshire cat using it’s appearances within those narrative arcs.

First, in which texts does a Cheshire cat turn up?

cracks knuckles

After a bit of tinkering and a bit of a wait, I was able to pull out the Proj. Gutenberg index, parse out the book ids, construct urls for text files, and obtain complete versions of the 136 texts containing the phrase “Cheshire cat” or “Cheshire puss”. Code in case you feel like tinkering on something similar.

Now to find the plot twists. This is familiar territory for anyone used to looking at fluctuations in stock price or detecting chemical signals in measurements from NMR/MS/etc., and in deed, there’s a variety of R packages that already do this off the shelf. For no reason in particular, I went with quantmod this time around.

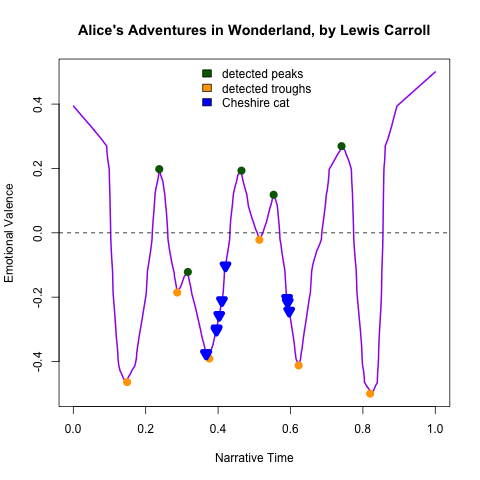

So can we actually detect the plot turns and confirm that the cat appears somewhere meaningful in “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland”, which first popularized the character? I loaded the sentences and assigned sentiments as before. Then I identified Cheshire cat appearances by looking for sentences containing any of “Cheshire cat”, ” Cat “, or “Cheshire puss”, which should cover most true appearances, and omit the broader discussion of cats in the beginning. Again code is here.

In this case, the Cheshire cat first turns up just before the third trough in the plot progression, as Alice enters the Duchess’ house and finds the cat grinning on the hearth. Things deteriorate a bit as the Duchess asks the cook to butcher Alice, but the sentiment recovers when the focus shifts to abusive parenting. The passage is below, the turning point is in bold.

======================================================

I didnt know that Cheshire cats always grinned; in fact, I didnt knowthat cats COULD grin.

They all can, said the Duchess; and most of em do.

I dont know of any that do, Alice said very politely, feeling quitepleased to have got into a conversation.

You dont know much, said the Duchess; and thats a fact.

Alice did not at all like the tone of this remark, and thought it wouldbe as well to introduce some other subject of conversation. While shewas trying to fix on one, the cook took the cauldron of soup off thefire, and at once set to work throwing everything within her reach atthe Duchess and the baby–the fire-irons came first; then followed ashower of saucepans, plates, and dishes. The Duchess took no notice ofthem even when they hit her; and the baby was howling so much already,that it was quite impossible to say whether the blows hurt it or not.

Oh, PLEASE mind what youre doing! cried Alice, jumping up and down inan agony of terror. Oh, there goes his PRECIOUS nose; as an unusuallylarge saucepan flew close by it, and very nearly carried it off.

If everybody minded their own business, the Duchess said in a hoarsegrowl, the world would go round a deal faster than it does.

Which would NOT be an advantage, said Alice, who felt very glad to getan opportunity of showing off a little of her knowledge. Just think ofwhat work it would make with the day and night! You see the earth takestwenty-four hours to turn round on its axis–

Talking of axes, said the Duchess, chop off her head!

Alice glanced rather anxiously at the cook, to see if she meant to takethe hint; but the cook was busily stirring the soup, and seemed not tobe listening, so she went on again: Twenty-four hours, I THINK; or isit twelve? I–

Oh, dont bother ME, said the Duchess; I never could abide figures!And with that she began nursing her child again, singing a sort oflullaby to it as she did so, and giving it a violent shake at the end ofevery line:

Speak roughly to your little boy,And beat him when he sneezes:He only does it to annoy,Because he knows it teases.

CHORUS.

======================================================

May be the whole situation could’ve been avoided if Alice didn’t feel the need to recover from not knowing that Cheshire cats grin? Who knows? But, as long as we can agree that in terms of sentiment, being raised by an abusive noble is just a first world problem relative to having a murder request to your name, then things again mostly seem to check out.

Or may be I’m just cherry-picking? After all, not every Cheshire cat appearance is near a plot turn. But neither is it reasonable to expect a random recurring character to only turn up at meaningful plot points. So for now, I’ll just focus on the one cat appearance closest to a critical point in each text and distinguish among the types of critical points that are closest. As a baseline, we can use the distribution of nearest peak types for all sentences that didn’t mention the Cheshire cat in the texts which contained it. Ran the numbers, counts below. |Critical point position|Critical point type|No cat (freq.)|Cat (freq.)| |after|peak|171316 (0.221)|28 (0.201)|

28 (0.201)

| after | trough | 224358 (0.299) | 50 (0.368) |

50 (0.368)

| before | peak | 148931 (0.192) | 24 (0.176) |

24 (0.176)

| before | trough | 232068 (0.289) | 34 (0.250) |

34 (0.250)

There seems to be some enrichment of cat appearances before peak troughs (where the trough appears after the cat in the table). We can ask if these numbers are greater than what we would expect by chance in a variety of ways. I should probably put together a blooper reel of things I tried that didn’t work in a future post, but for now I’ll stick with one simple thing that did.

Avoiding the need for any of the assumptions of Chi-squared tests, I drew 10,000 samples from a multinomial distribution with parameters given by the frequencies in the “no cat” baseline column, and with each sample containing the same total number of counts as the cat column. Obviously this can also be done using a series of evaluations of binomial distributions, but sampling from a multinomial requires fewer keystrokes here. The probabilities of observing at least as many cat placements as the amount we did observe are below. |Critical point position|Critical point type|Prob| |After|Both|0.0523| |Both|Trough|0.2155| |After|Trough|0.0167| |Before|Trough|0.8753| |After|Peak|0.6127| |Before|Peak|0.6240|

Sure enough, it’s pretty unlikely to have observed this many Cheshire cat appearances before plot troughs purely by chance.

And so long story short, Cheshire cats do seem to have a preference for turning up just before things start to get better.

Like this:

Like Loading…