Seriously. Hear me out on this.

The more I learn about ML, the more I see the number of similarities there are between life and machine learning concepts.

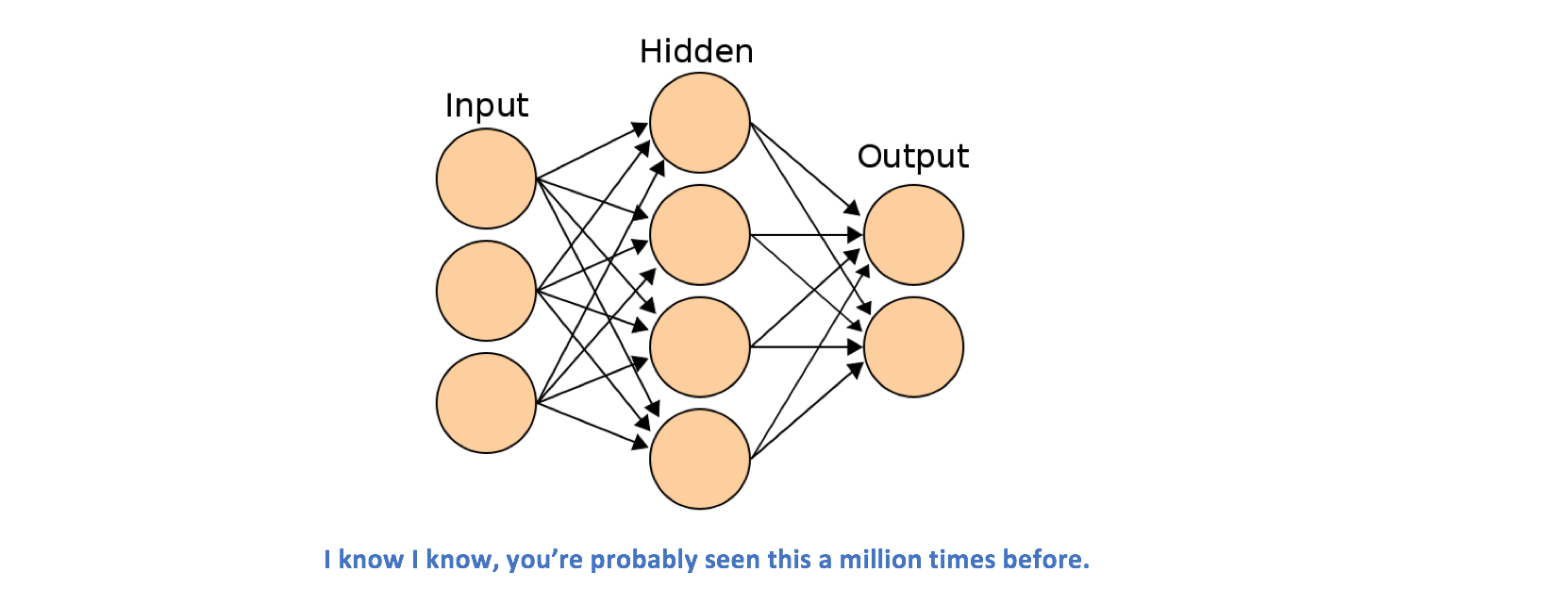

Specifically, let’s think about neural networks.

Let’s think of a neural net that has a bunch of input nodes and one output node. The input features are encapsulated in some input vector x, and we’d like to come up with a single scalar prediction ŷ. The way you compute ŷ is by passing x through a series of linear operations with weight matrices mixed in with a couple activation functions. Simple enough. But in order to get accurate ŷ predictions, we need to first train our network.

When training neural networks, the goal is to be able to minimizea loss function.

That’s the name of the game. We want to be able to minimize the difference between the actual labels in our training set and our predictions, and adjust the weights of our network in hope of training it well enough so that it can generalize to test examples.

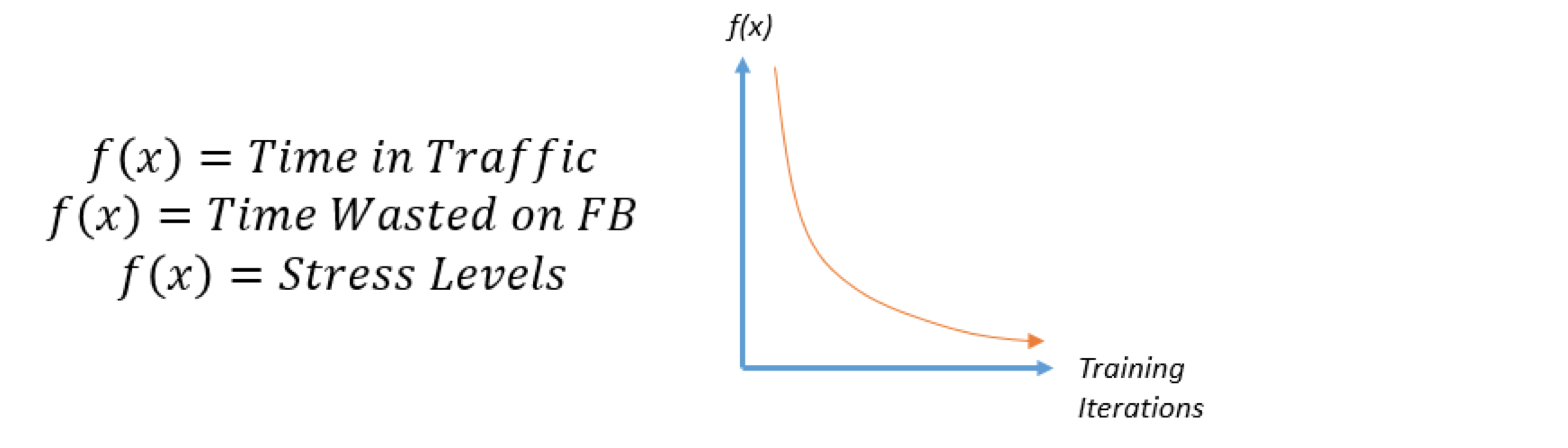

I realized that this idea of a minimizing a loss function kind of relates to our daily lives. Think about it. When you drove to work/school this morning, did you take the fastest route possible or did you take a couple of random highways and a few side streets, eventually ending up at your destination? When you have an important project due, do you waste time on Facebook or do you buckle down and put away your phone (*Hopefully *there’s only one right answer here). When you’re a coder who’s working on a couple of difficult assignments, do you calmly split up the jobs and work on each one at a time or do you panic and work for 36 hours straight to get them done (Yes, there is a masochistic answer but we’re not going with that).

The idea here is that we’re all, consciously or subconsciously, solving optimization problems every single day. We’re always trying to minimize the amount of stress, the number of distractions, and the time it takes to do something.

The first time you drove to work/school, it’s very possible that you could’ve taken an inefficient and long route. However, over time, you start to recognize traffic and shortcuts, and eventually start to minimize the time spent driving.

What about those times where you can’t seem to break the habit of checking your News Feed every hour, or the times where you feel like there’s no way to decrease the amount of soul crushing stress of school or work? Well, we can think of those as justlocal minima or saddle points. In ML, these are points in the vector space where the gradient is close to 0, thus making it difficult to minimize f(x) any further. In life, these are moments where we feel like there’s nothing we can really do, no changes we can make to alleviate the current situation. Fighting these local minima and saddle points requires second order optimization and some other complex techniques. From a high level, they look for ways to escape the unfavorable points by computing additional information in the form of Hessians, curvature info, etc. So, in life, when you feel like you’re in one of those unpleasant local minimas, just remember to always look around because there could always useful information to help you out of your current situation and further minimize your f(x).

Alright, let’s look at a different part of the ML pipeline now.

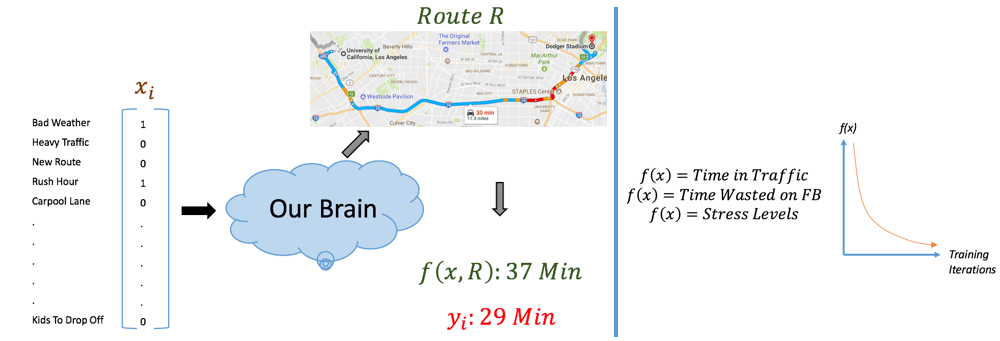

One of the other main components in your ML model is your training dataset. You have some set X where each xi ∈ X is a particular collection of features (in vector form) describing the input example, and you have some set Y where each yi ∈ Y is a label that describes the category for classification or a real valued number for regression. These examples are there to help us train our network to output accurate ŷ values.

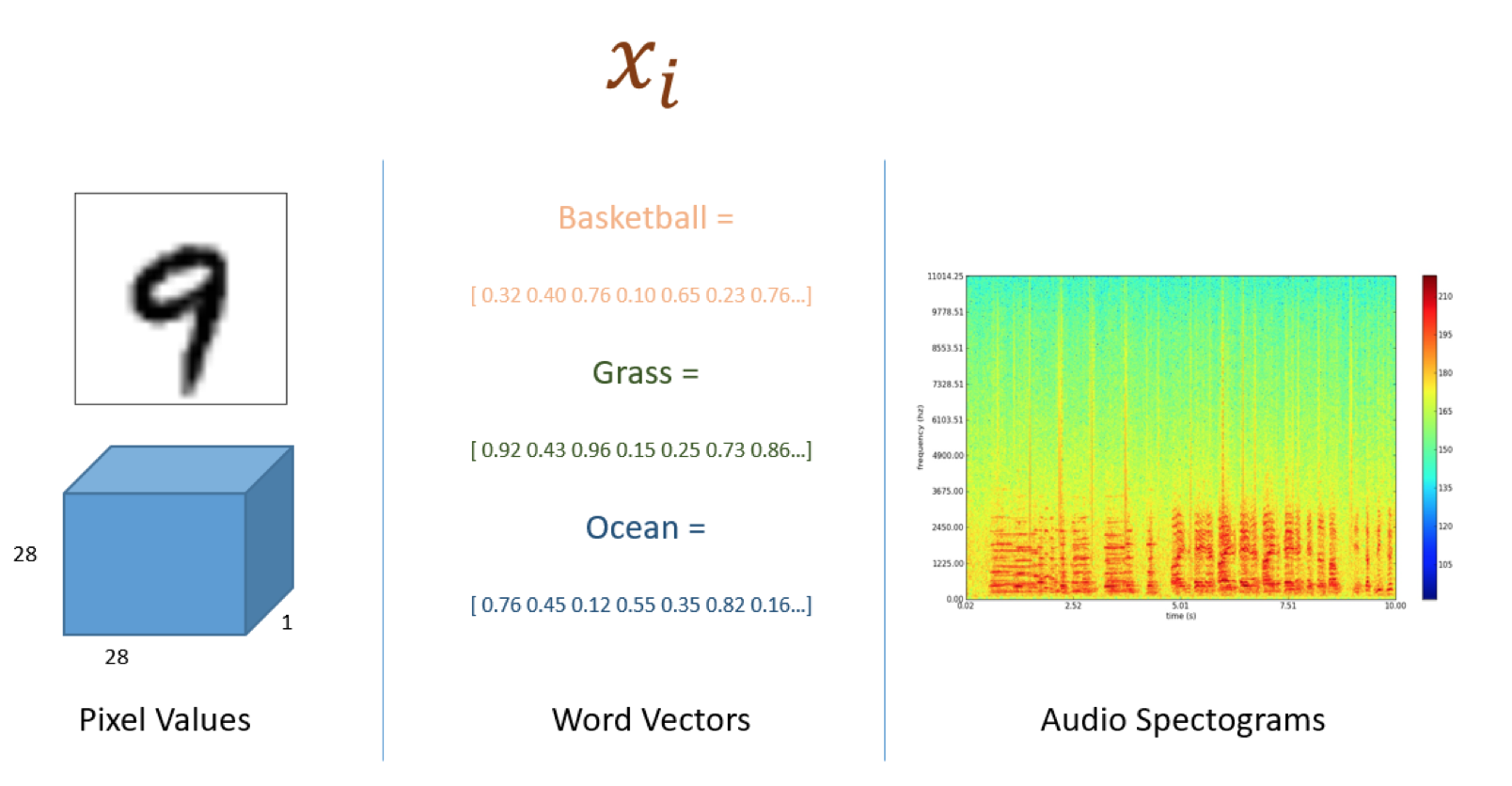

If our lives have so many optimization problems, what are the xi’s and yi’s? In ML problems, xi can be a matrix of pixel values, a word vector, or the spectrogram of an audio clip, while yi is often a category or a real valued number.

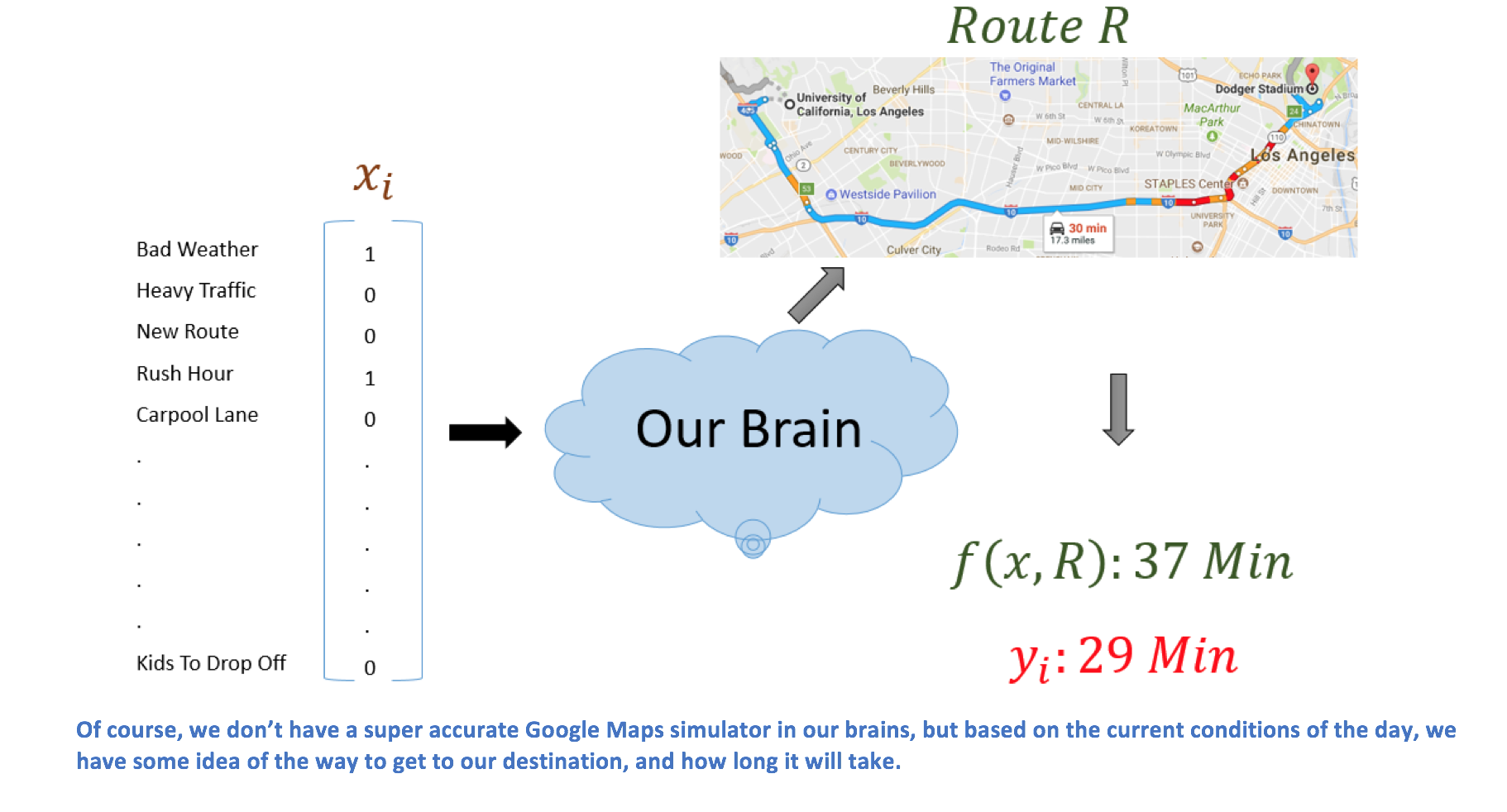

Let’s take the example of driving to work. In real life, we can think of that input vector as describing the set of circumstances surrounding that day. Was there an accident on the major freeway? Is there bad weather right now? Am I leaving during rush hour? All of this information is encapsulated in some mental representation in our brains, and is processed to be able to determine a driving route R. Based on that route, we record the actual time it took to reach the destination, which we’ll denote f(x, R). We train our mental model so that f(x, R) gets as close to yi, the optimal amount of time it takes to get to the destination.

You can think of every single day as one example pair (xi, yi) in our training set (X,Y). Each xi represents the conditions and each yi represents the optimal time taken. In ML, we train our network by looking at our training examples and updating weights based on those example pairs. For us, we’re training our own network to get better and better at finding routes and minimizing the difference between f(x, R) and yi by looking at our own past experiences. These act as *our *training set. We think about that day we could have turned left at that side street. We think about the times we should’ve taken 101 instead of 280. And we also think about the times we made it to work in only 10 minutes because we merged into the fastest lane in the freeway. We’re constantly using this training set as an indicator for how we should act in the future.

Alright let’s switch gears a bit.

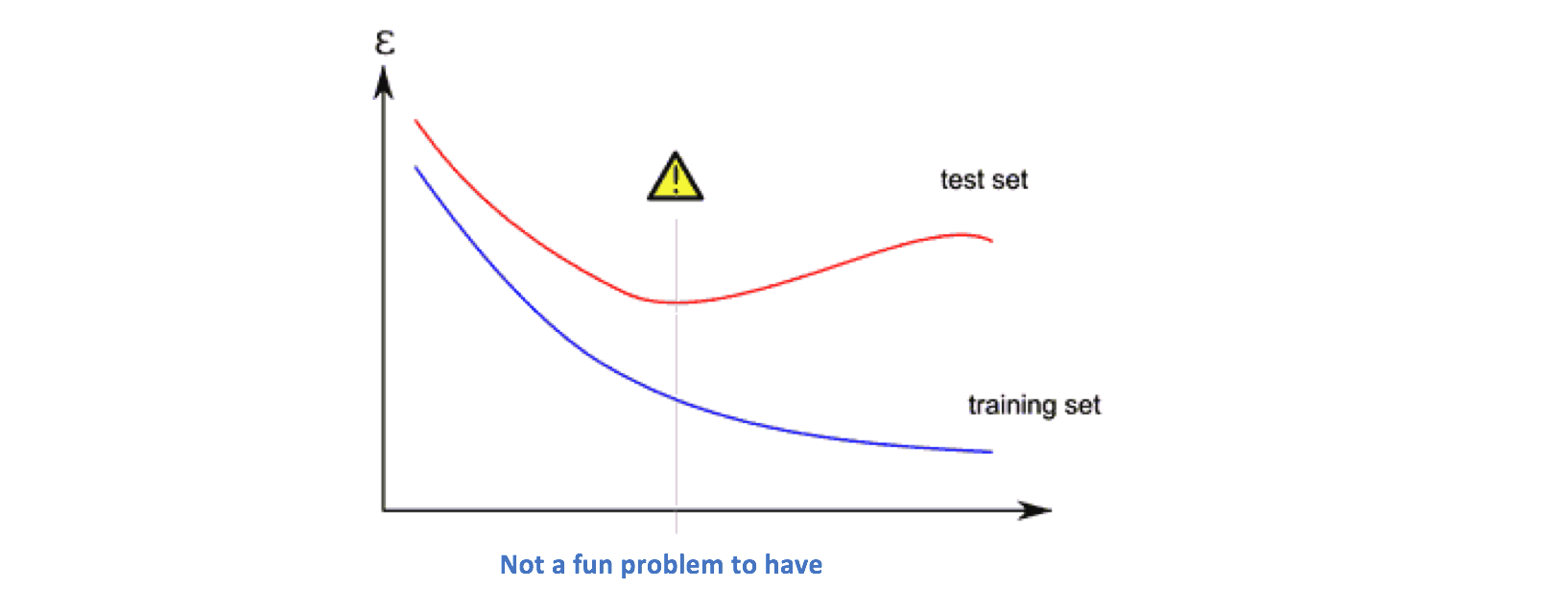

One of the chief concerns with machine learning is the prospect of overfitting. This is the moment where your ML model fits too well to the dataset that it’s trained on. This results in poor generalization performance on data it hasn’t seen before.

In life, this can happen when perhaps we spend too much time looking at the past moments in our lives as indicators of what’s to come. Our minds are so glued to the experiences in our training set that we aren’t able to respond well to unique events we haven’t encountered yet.

It’s when we think about our previous breakups as indicator to how future relationships will turn out. It’s when we’re unconfident about a final when we remember how poorly we did on the midterms. Overfitting can have disastrous consequences as test accuracy for a model is almost never as good as the accuracy during training. When we have that mentality of replicating our behavior and thought processes based on past experiences, we become inflexible and can’t properly adapt to what’s right in front us. If we’re constantly thinking about that time we forgot our lines in the annual elementary school play, we’ll never have the confidence and belief to take the stage once more (True story).

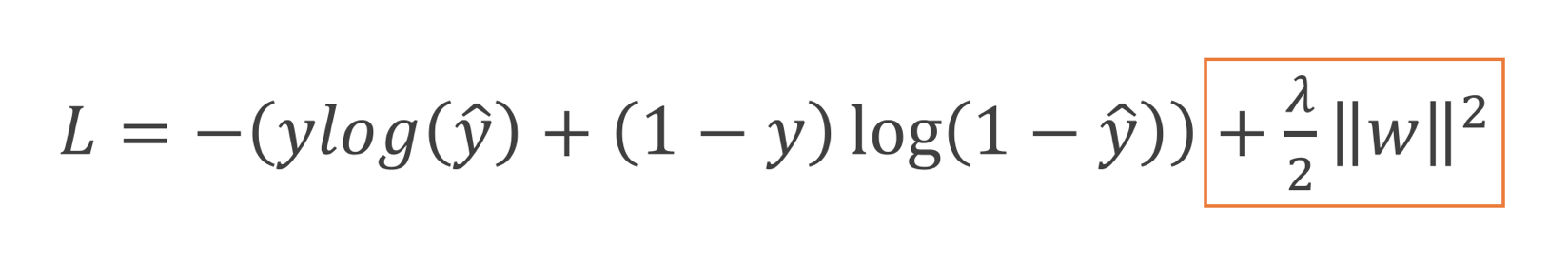

What’s the solution to this? Well, in machine learning, we use regularizers. The first form (and the most common) of regularization that I first learned about was L2 regularization or weight decay.

This type of regularization is basically imposing a soft constraint on the cost function. We’re telling the network “Hey, we want you to minimize the loss from the training examples, but it would also be cool if you keep the weights of your network at a low value because your cost is gonna increase a lot if those values are high” (Btw, a hard constraint would mean that we put specific limits on the weight values and don’t allow them to increase beyond some threshold).

So how does this regularizer help in real life? Let’s consider that scenario of finding a good relationship after past experiences with breakups. Let’s say that we have some f(x) which represents the overall happiness you get from the relationship. Ideally, we’d like to maximize this (or minimize its negative). Given the low past values for* f(x), there’s a chance we could overfit to the training data and simply fall down the same holes as the previous relationships. So instead of just focusing on maximizing *f(x), we should also pay attention to how our weights w are structured. Maybe we should impose soft constraints on the amount (or lack) of communication or specific shared activities. This forces us to stop fitting so tightly to the past experiences, but instead focusing on adjusting parameters in ways that can help us generalize better to new opportunities.

Other regularizers often come in the form of dropout, a simpler network, and data augmentation. Maybe we can “forget” about some of the features describing a particular event in our past. Maybe we can stop thinking about so many different features or complicated computations or representations in our attempts to get a favorable output value. Or maybe we can simply obtain more data by just living through more experiences.

Alright, last one.

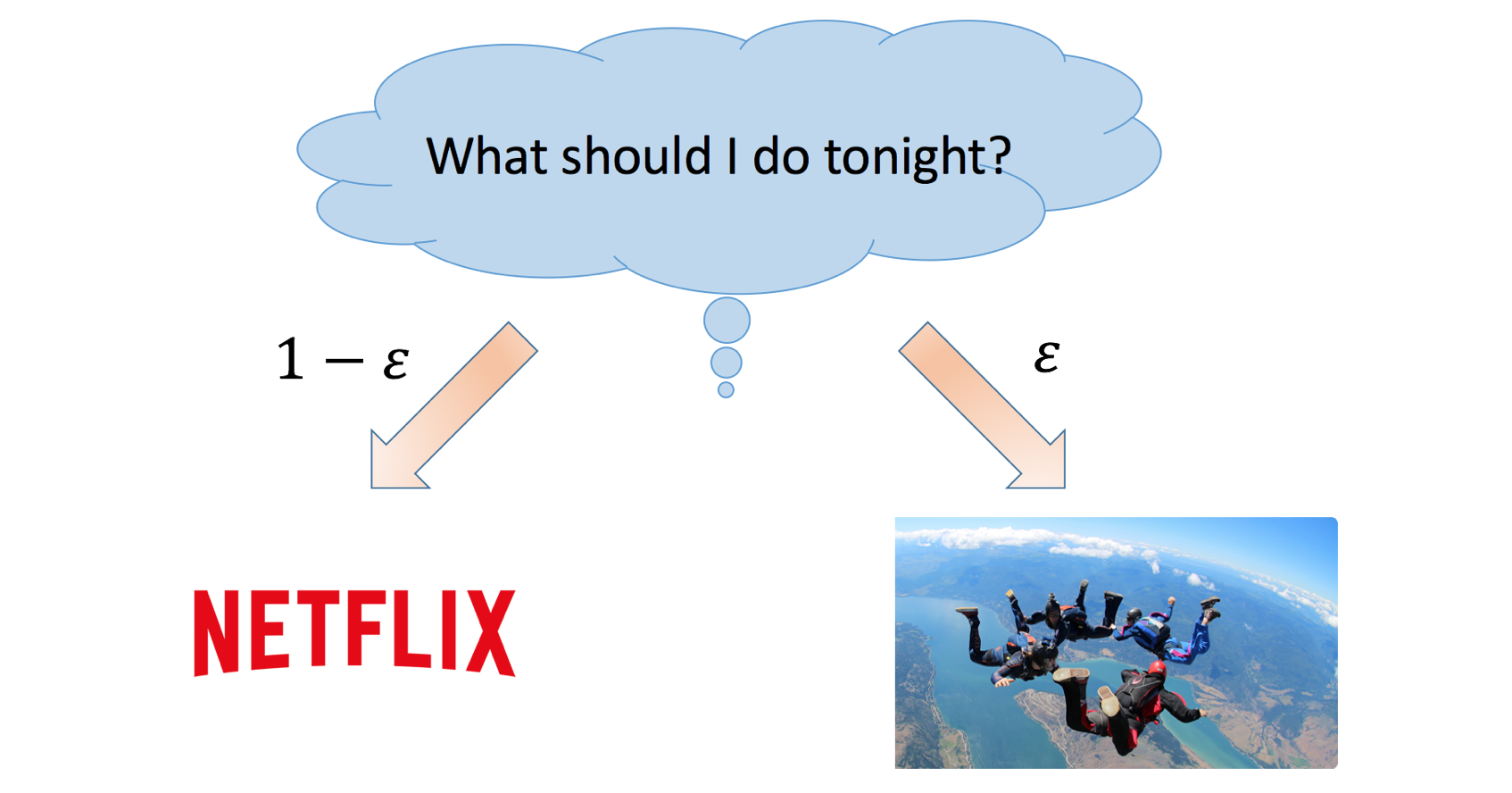

Another cool analogy is that of the epsilon greedy policy. This is a term used in reinforcement learning to fight the problem of exploration vs exploitation. The basic idea is that the RL agent will take a random action (instead of the optimal action according to its current policy) with probability ε, in hope of searching a larger area of the state space, and eventually getting a better reward.

You can relate this to life whenever you’re thinking of trying something new and going outside your comfort zone. While your initial thought process might be to just do the activity that you know will give you a solid reward (e.g Watching Netflix at home), you could explore a different state space and try an activity you haven’t done before, like oh I don’t know, go sky diving. The reward of such an activity might be lower and you may end up hating it and having a perpetual fear of heights, but there’s also a chance that it could be an absolutely incredible experience that was much better than any House of Cards episode.

So what do we do? Do we go with the activity we know will give us the highest reward or do we try something new?

Does this all make sense? Yeah? No?

Or maybe I’m going crazy because of the amount of ML related Arxiv papers I’ve read over the past month? Not sure **.

Concepts I Couldn’t Find Analogies For:

-

Batch Norm

-

Adam (I do have a friend named Adam, don’t think that counts though)

-

Weight Initialization

-

Cross Validation

-

Backpropagation

Dueces. **