As I move through my 20’s I’m consistently delighted by the subtle ways in which I’ve changed.

Will at 22: Reggaeton is a miserable, criminal assault to my ears. Will at 28: Despacito (Remix) for breakfast, lunch, dinner.

Will at 22: Western Europe is boring. No — I’ve seen a lot of it! Everything is too clean, too nice, too perfect for my taste. Will at 28, in Barcelona, after 9 months in Casablanca: Wait a second: I get it now. What is this summertime paradise of crosswalks, vehicle civility and apple-green parks and where has it been all my life?

Will at 22: Emojis are weird. Will at 28: 🚀 🤘 💃� 🚴� 🙃.

Emojis are an increasingly-pervasive sub-lingua-franca of the internet. They capture meaning in a rich, concise manner — alternative to the 13 seconds of mobile thumb-fumbling required to capture the same meaning with text. Furthermore, they bring two levels of semantic information: their context within raw text and the pixels of the emoji itself.

Question-answer models

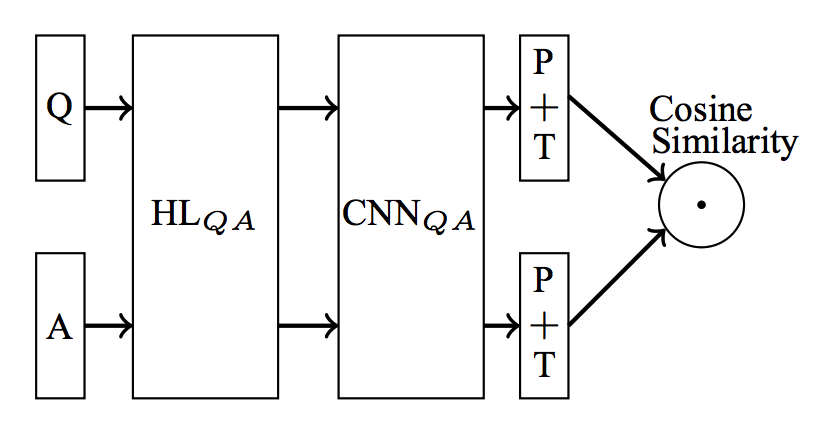

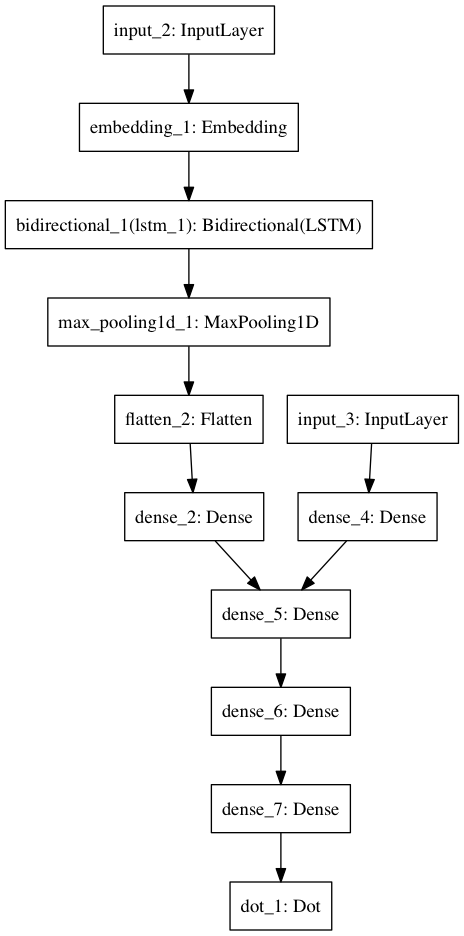

The original aim of this post was to explore Siamese question-answer models of the type typically applied to the InsuranceQA Corpus as introduced in “Applying Deep Learning To Answer Selection: A Study And An Open Task” (Feng, Xiang, Glass, Wang, & Zhou, 2015). We’ll call them SQAM for clarity. The basic architecture looks as follows:

By layer and in general terms:

-

An input — typically a sequence of token ids — for both question (Q) and answer (A).

-

An embedding layer.

-

Convolutional layer(s), or any layers that extract features from the matrix of embeddings. (A matrix, because the respective inputs are sequences of token ids; each id is embedded into its own vector.)

-

A max-pooling layer.

-

A

tanhnon-linearity. -

The cosine of the angle between the resulting, respective embeddings.

As canonical recommendation

Question answering can be viewed as canonical recommendation: embed entities into Euclidean space in a meaningful way, then compute dot products between these entities and sort the list. In this vein, the above network is (thus far) quite similar to classic matrix factorization yet with the following subtle tweaks:

-

Instead of factorizing our matrix via SVD or OLS we build a neural network that accepts

(question, answer), i.e.(user, item), pairs and outputs their similarity. The second-to-last layer gives the respective embeddings. We train this network in a supervised fashion, optimizing its parameters via stochastic gradient descent. -

Instead of jumping directly from input-index (or sequence thereof) to embedding, we first compute convolutional features.

In contrast, the network above boasts one key difference: both question and answer, i.e. user and item, are transformed via a single set of parameters — an initial embedding layer, then convolutional layers — en route to their final embedding.

Furthermore, and not unique to SQAMs, our network inputs can be any two sequences of (tokenized, max-padded, etc.) text: we are not restricted to only those observed in the training set.

Question-emoji models

Given my accelerating proclivity for the internet’s new alphabet, I decided to build text-question-emoji-answer models instead. In fact, this setup gives an additional avenue for prediction: if we make a model of the answers (emojis) themselves, we can now predict on, i.e. compute similarity with, each of

-

Emojis we saw in the training set.

-

New emojis, i.e. either not in the training set or new (like, released months from now) altogether.

-

Novel emojis generated from the model of our data. In this way, we could conceivably answer a question with: “we suggest this new emoji we’ve algorithmically created ourselves that no one’s ever seen before.”

Let’s get started.

Convolutional variational autoencoders

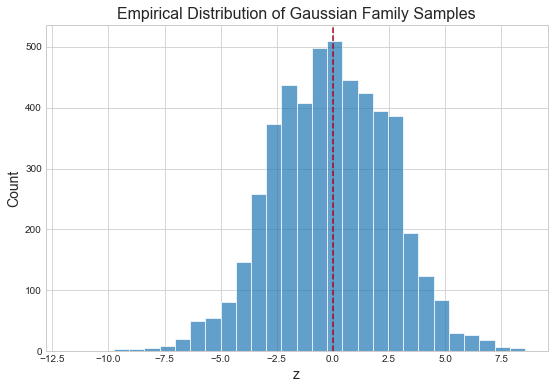

Variational autoencoders are comprised of two models: an encoder and a decoder. The encoder embeds our 872 emojis of size ((36, 36, 4)) into a low-dimensional latent code, (z_e \in \mathbb{R}^{16}), where (z_e) is a sample from an emoji-specific Gaussian. The decoder takes as input (z_e) and produces a reconstruction of the original emoji. As each individual (z_e) is normally distributed, (z) should be distributed normally as well. We can verify this with a quick simulation.

Training a variational autoencoder to learn low-dimensional emoji embeddings serves two principal ends:

-

We can feed these low-dimensional embeddings as input to our SQAM.

-

We can generate novel emojis with which to answer questions.

As the embeddings in #1 are multivariate Gaussian, we can perform #2 by passing Gaussian samples into our decoder. We can do this by sampling evenly-spaced percentiles from the inverse CDF of the aggregate embedding distribution:

NB: norm.ppf does not accept a size parameter; I believe sampling from the inverse CDF of a multivariate Gaussian is non-trivial in Python.

Similarly, we could simply iterate over (mu, sd) pairs outright:

The ability to generate new emojis via samples from a well-studied distribution, the Gaussian, is a key reason for choosing a variational autoencoder.

Finally, as we are working with images, I employ convolutional intermediary layers.

Data preparation

Split data into train, validation sets

Additionally, scale pixel values to ([0, 1]).

Before we begin, let’s examine some emojis.

Model emojis

Variational layer

This is taken from a previous post of mine, Transfer Learning for Flight Delay Prediction via Variational Autoencoders.

Autoencoder

The full model encoder_decoder is composed of separate models encoder and decoder. Training the former will implicitly train the latter two; they are available for our use thereafter.

The above architecture takes inspiration from Keras, Edward and the GDGS (gradient descent by grad student) method by as discussed by Brudaks on Reddit:

A popular method for designing deep learning architectures is GDGS (gradient descent by grad student). This is an iterative approach, where you start with a straightforward baseline architecture (or possibly an earlier SOTA), measure its effectiveness; apply various modifications (e.g. add a highway connection here or there), see what works and what does not (i.e. where the gradient is pointing) and iterate further on from there in that direction until you reach a (local?) optimum.

I’m not a grad student but I think it still plays.

Fit model

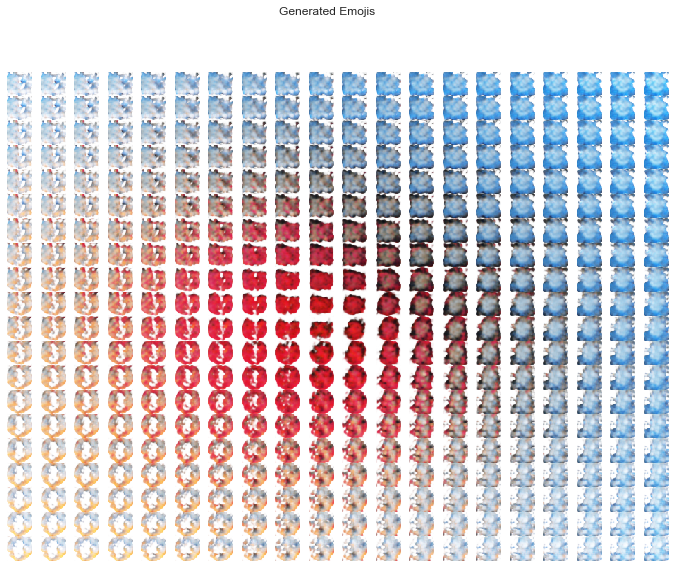

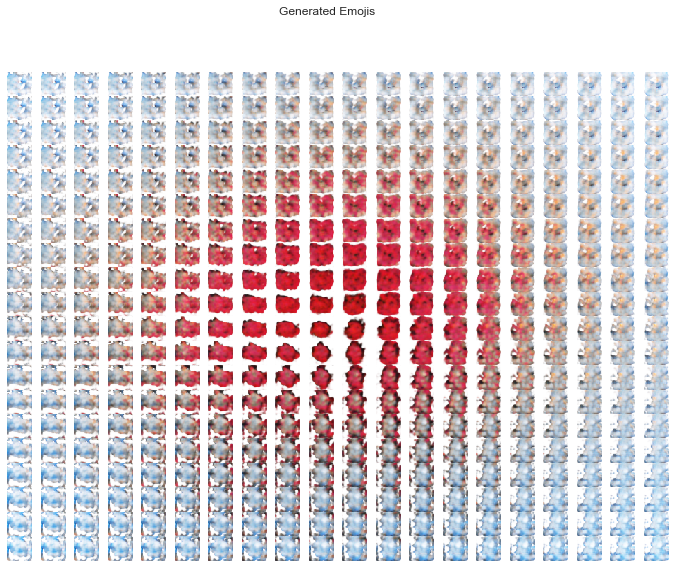

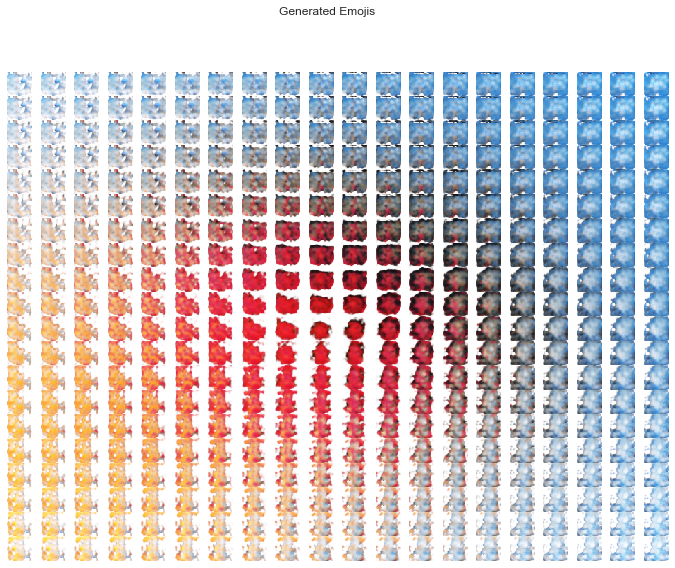

Generate emojis

As promised we’ll generate emojis. Again, latent codes are distributed as a (16-dimensional) Gaussian; to generate, we’ll simply take samples thereof and feed them to our decoder.

While scanning a 16-dimensional hypercube, i.e. taking (evenly-spaced, usually) samples from our latent space, is a few lines of Numpy, visualizing a 16-dimensional grid is impractical. In solution, we’ll work on a 2-dimensional grid while treating subsets of our latent space as homogenous.

For example, if our 2-D sample were (0, 1), we could posit 16-D samples as:

Then, if another sample were (2, 3.5), we could posit 16-D samples as:

There is no math here: I’m just creating 16-element lists in different ways. We’ll then plot “A-lists,” “B-lists,” etc. separately.

As our emojis live in a continuous latent space we can observe the smoothness of the transition from one to the next.

The generated emojis have the makings of maybe some devils, maybe some bubbles, maybe some hearts, maybe some fish. I doubt they’ll be featured on your cell phone’s keyboard anytime soon.

Text-question, emoji-answer

I spent a while looking for an adequate dataset to no avail. (Most Twitter datasets are not open-source, I requested my own tweets days ago and continue to wait, etc.) As such, I’m working with the Twitter US Airline Sentiment dataset: tweets are labeled as positive, neutral, negative which I’ve mapped to ğŸ�‰, 😈 and 😡.

Contrastive loss

We’ve thus far discussed the SQAM. Our final model will make use of two SQAM’s in parallel, as follows:

-

Receive

(question, correct_answer, incorrect_answer)triplets as input. -

Compute the cosine similarity between

question,correct_answerviaSQAM_1—correct_cos_sim. -

Compute the cosine similarity between

question,incorrect_answerviaSQAM_2—incorrect_cos_sim.

The model is trained to minimize the following: max(0, margin - correct_cos_sim + incorrect_cos_sim), a variant of the hinge loss. This ensures that (question, correct_answer) pairs have a higher cosine similarity than (question, incorrect_answer) pairs, mediated by margin. Note that this function is differentiable: it is simply a ReLU.

Architecture

A single SQAM receives two inputs: a question — a max-padded sequence of token ids — and an answer — an emoji’s 16-D latent code.

To process the question we employ the following steps, i.e. network layers:

- Select the pre-trained-with-Glove 100-D embedding for each token id. This gives a matrix of size

(MAX_QUESTION_LEN, GLOVE_EMBEDDING_DIM).

Pass the result through a bidirectional LSTM — (apparently) key to current state-of-the-art results in a variety of NLP tasks. This can be broken down as follows:

-

Initialize two matrices of size

(MAX_QUESTION_LEN, LSTM_HIDDEN_STATE_SIZE):forward_matrixandbackward_matrix. -

Pass the sequence of token ids through an LSTM and return all hidden states. The first hidden state is a function of, i.e. is computed using, the first token id’s embedding; place it in the first row of

forward_matrix. The second hidden state is a function of the first and second token-id embeddings; place it in the second row offorward_matrix. The third hidden state is a function of the first and second and third token-id embeddings, and so forth. -

Do the same thing but pass the sequence to the LSTM in reverse order. Place the first hidden state in the last row of

backward_matrix, the second hidden state in the second-to-last row ofbackward_matrix, etc. -

Concatenate

forward_matrixandbackward_matrixinto a single matrix of size(MAX_QUESTION_LEN, 2 * LSTM_HIDDEN_STATE_SIZE).

Max-pool.

-

Flatten.

-

Dense layer with ReLU activations, down to 10 dimensions.

To process the answer we employ the following steps:

-

Dense layer with ReLU activations.

-

Dense layer with ReLU activations, down to 10 dimensions.

Now of equal size, we further process our question and answer with a single set of dense layers — the key difference between a SQAM and (the neural-network formulation of) other canonical (user, item) recommendation algorithms. The last of these layers employs tanh activations as suggested in Feng et al. (2015).

Finally, we compute the cosine similarity between the resulting embeddings.

Prepare questions, answers

Import tweets

| index | text | airline_sentiment | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 2076 | @united that’s not an apology. Say it. | negative |

| 1 | 7534 | @JetBlue letting me down in San Fran. No Media… | negative |

| 2 | 14441 | @AmericanAir where do I look for cabin crew va… | neutral |

| 3 | 13130 | @AmericanAir just sad that even after spending… | negative |

| 4 | 3764 | @united What’s up with the reduction in E+ on … | negative |

Embed answers into 16-D latent space

Additionally, scale the latent codes; these will be fed to our network as input.

We’ve now built (only) one (question, correct_answer, incorrect_answer) training triplet for each ground-truth (question, correct_answer). In practice, we should likely have many more, i.e. (question, correct_answer, incorrect_answer_1), (question, correct_answer, incorrect_answer_2), ..., (question, correct_answer, incorrect_answer_n).

Construct sequences of token ids

Split data into train, validation sets

NB: We don’t actually have y values: we pass (question, correct_answer, incorrect_answer) triplets to our network and try to minimize max(0, margin - correct_cos_sim + incorrect_cos_sim). Notwithstanding, Keras requires that we pass both x and y (as Numpy arrays); we pass the latter as a vector of 0’s.

Build embedding layer from Glove vectors

Build Siamese question-answer model (SQAM)

GDGS architecture, ✌�.

Build contrastive model

Two Siamese networks, trained jointly so as to minimize the hinge loss of their respective outputs.

Build prediction model

This is what we’ll use to compute the cosine similarity of novel (question, answer) pairs.

Fit contrastive model

Fitting contrastive_model will implicitly fit prediction_model as well, so long as the latter has been compiled.

Predict on new tweets

“@united Flight is awful only one lavatory functioning, and people lining up, bumping, etc. because can’t use 1st class bathroom. Ridiculous”

“@usairways I’ve called for 3 days and can’t get thru. is there some secret method i can use that doesn’t result in you hanging up on me?”

“@AmericanAir Let’s all have a extraordinary week and make it a year to remember #GoingForGreat 2015 thanks so much American Airlines!!!”

Tweet #1

Tweet #2

Tweet #3

Additionally, we can predict on the full set of emojis

Some emoji embeddings contain np.inf values, unfortunately. We could likely mitigate this by further tweaking the hyperparameters of our autoencoder.

Tweet #1

Tweet #2

Tweet #3

Not particularly useful. These emojis have 0 notion of sentiment, though: the model is simply predicting on their (pixel-based) latent codes.

Future work

In this work, we trained a convolutional variational autoencoder to model the distribution of emojis. Next, we trained a Siamese question-answer model to answer text questions with emoji answers. Finally, we were able to use the latter to predict on novel emojis from the former.

Moving forward, I see a few logical steps:

-

Use emoji embeddings that are conscious of sentiment — likely trained via a different network altogether. This way, we could make more meaningful (sentiment-based) predictions on novel emojis.

-

Predict on emojis generated from the autoencoder.

-

Add 1-D convolutions to the text side of the SQAM.

-

Add an “attention” mechanism — the one component missing from the “embed, encode, attend, predict” dynamic quartet of modern NLP.

-

Improve the stability of our autoencoder so as to not produce embeddings containing

np.inf.

Sincere thanks for reading, and emojis 🤘.

Code

The repository and rendered notebook for this project can be found at their respective links.