This article builds on two previous articles about cutting a circular cake into eight equal sized pieces.

(If needed, you can read those earlier articles here and here for background).

There are ways to do better in some of the families of solutions I gave in the previous articles; solutions can be found that reduce the total length of the cut needed, though they add additional criteria, such as requiring cuts that do not go edge-edge, or increase the number of discrete cuts needed.

It’s clear that I poorly defined the problem. I’ll attempt to redress that with this article. If we wanted to cut a cake into eight pieces of equal size (not shape), what is the shortest overall length of cut needed? We’ll group families of solutions based on the number of discrete straight cuts used. We’re not allowed to restack pieces after any cut, and cuts do not have to go from edge to edge.

All cuts have to be orthoganol to the surface of the cake (meaning this is really a problem of how to carve up a circle into eight regions of equal area).

Below are what I think are the optimal solutions. If you can do better, please let me know, and I’ll continue to update!

We’re assuming a normalized circle with unit radius, so all lengths are quoted based on this.

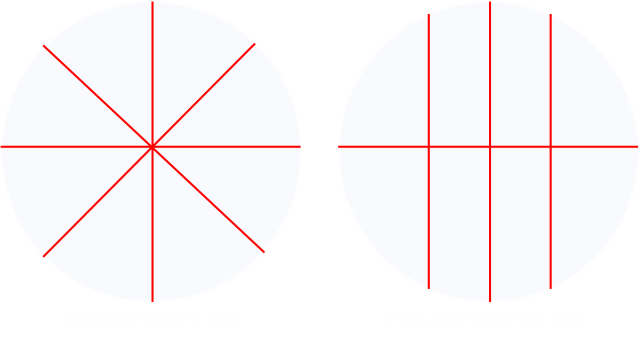

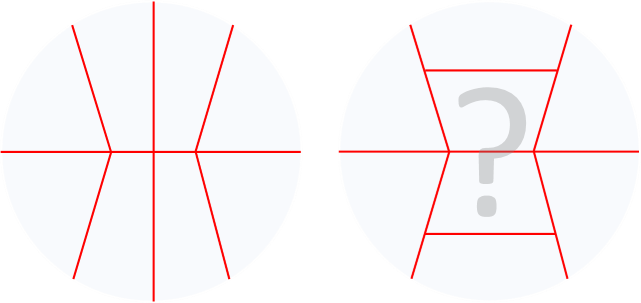

Four Cuts

Becuase we’re not able to restack the pieces, the minimum number of cuts is four. The traditional sector cut requires 8 units, and by using the technique calculated in the first article, we can reduce this down to 7.66 units (show below right).

The solution on the right also has the bonus that cuts are still made edge-to-edge. This was the results I showed in my first article that started all this follow-up! (I poorly stated the problem).

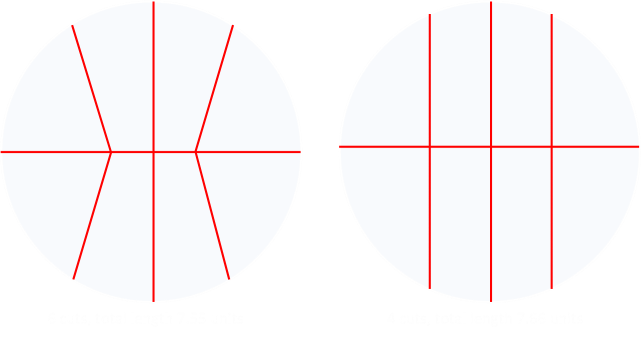

Six Cuts

We’ll look at six cuts as way to get to five cuts.

If cuts don’t need to need to go edge-edge, then we can do better by angling the two outer lines slightly. Even though this results in a slightly longer cut, because of the circular cake, it allows more region on one side, and can be compensated by sliding the intersection point closer to the middle. There is an optimal angle, and this was covered in the Second article.

Even though these cuts are not all edge-edge, each of the cuts does, at least, have one vertex on the edge of the cake. This allows a cake carver to start each cut from the edge of the cake. No plunge cuts are needed! (This means that if you need to cut Grandama’s special fruit cake, you can still use a band saw with no problem).

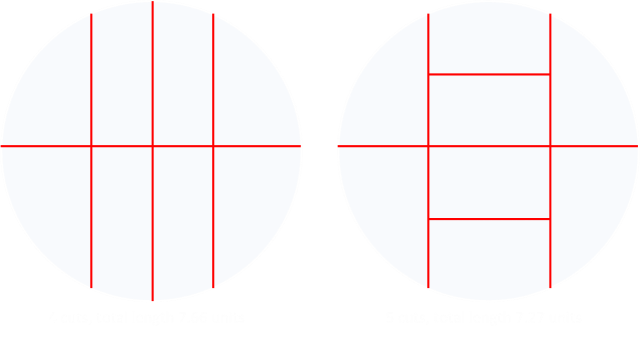

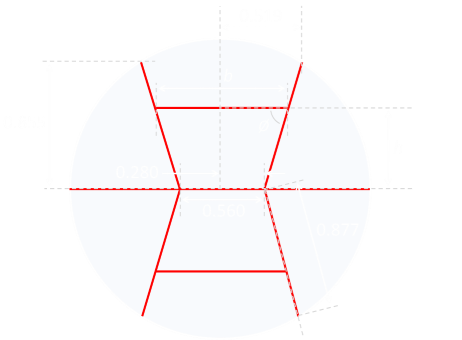

Five Cuts

We can make the total length of cuts needed shorter, and use one fewer cuts if we are allowed plunge cuts (cuts that do not start at any edge). This is something I overlooked on my first analysis. It’s an interesting diversion.

Rather than making the vertical bisecting cut (which would be two units long down the center), it’s more efficient to bisect each of the halves by a cut in the orthoganol direction).

This simple optimisation reduces the total legth down to ≈ 7.27 units. (Below are the details)

So if this technique works to reduce the length of the straight line solution above, it could also be applied to reduce the sloped solution below shown below right? Yes? Hold on, not so fast, we’ll need to check this out. Because of the slope, the closer to the edge this cross-bar goes, the wider it becomes (in the solution above, as the uprights are parallel, it does not matter where they go).

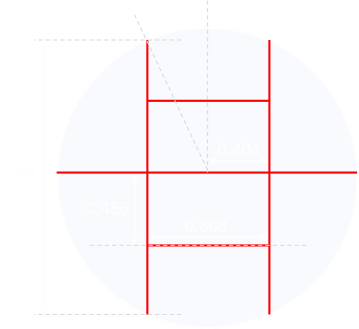

We’ll need to do some calculations:

We need to calculate b and h that enables a trapezium of one eighth of the area of the circle. We already know the slope of the cuts, so that angle can be determined.

A little bit of algebra gives the result of b ≈ 0.868, and h ≈ 0.550

This gives the total length of cuts at ≈ 7.25, which is close to the value we obtained from the straight-upright cut optimisation.

Below, to a higher precission, are the total lengths of the cuts using the various methods.

| Solution | Cut Length | % improvment | —— |

| Sector cut | 8.00000 | - | |

| Straight uprights | 7.65908 | 4.2615% | |

| Angled uprights | 7.50975 | 6.1281% | |

| Straight uprights and horizontal crossbar | 7.27497 | 9.0629% | |

| Angled uprights and horizontal crossbar | 7.24592 | 9.4260% |

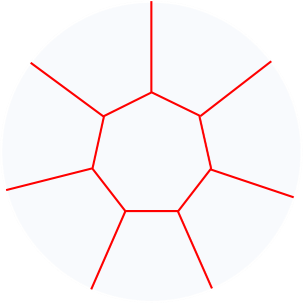

Fourteen cuts

If we graduate to fourteen cuts, as discussed in the last article, we can carve the cake into eight pieces by cutting a regular heptagon in the center and seven radial arms from the vetices.

| |Through symmetry, all the seven pieces around the annulus are the same shape, and make up of 7/8ths of the area of the circle. The regular heptagon in the center is made of 1/8th of the area.|Solution|Cut Length|% improvmentSector cut|8.00000|-|

|Straight uprights|7.65908|4.2615%|

|Angled uprights|7.50975|6.1281%|

|Straight uprights and horizontal crossbar|7.27497|9.0629%|

|Angled uprights and horizontal crossbar|7.24592|9.4260%|

|Heptagon center|6.64935|16.883%|

|Through symmetry, all the seven pieces around the annulus are the same shape, and make up of 7/8ths of the area of the circle. The regular heptagon in the center is made of 1/8th of the area.|Solution|Cut Length|% improvmentSector cut|8.00000|-|

|Straight uprights|7.65908|4.2615%|

|Angled uprights|7.50975|6.1281%|

|Straight uprights and horizontal crossbar|7.27497|9.0629%|

|Angled uprights and horizontal crossbar|7.24592|9.4260%|

|Heptagon center|6.64935|16.883%|

That’s quite an improvement!

The side of the heptagon is ≈ 0.328733, and the vertices are at a radius of ≈ 0.378826 (see previous article for details).

More Cuts …

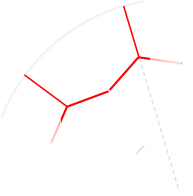

| |The total length of cake cut has two components; the radial spurs, and the sides of the heptagon. If we moved the vertices out a little, we could reduce the length of all of the outside cuts. A consequence of this is that the area of the center heptagon would be increased, and that of segments on the outside would decrease.We can compensate for this by adding an additional vertex in the middle of each of the sides of the heptagon, and pushing this into the heptagon to make it star shape. This will reduce the area of the center piece.As long as the additional length added to the sides by ‘buckling’ of the edges of the heptagon is less than the length reduced be moving out the vertices, it will increase the efficiency of the solution.|

|The total length of cake cut has two components; the radial spurs, and the sides of the heptagon. If we moved the vertices out a little, we could reduce the length of all of the outside cuts. A consequence of this is that the area of the center heptagon would be increased, and that of segments on the outside would decrease.We can compensate for this by adding an additional vertex in the middle of each of the sides of the heptagon, and pushing this into the heptagon to make it star shape. This will reduce the area of the center piece.As long as the additional length added to the sides by ‘buckling’ of the edges of the heptagon is less than the length reduced be moving out the vertices, it will increase the efficiency of the solution.|

We can compensate for this by adding an additional vertex in the middle of each of the sides of the heptagon, and pushing this into the heptagon to make it star shape. This will reduce the area of the center piece.

|There are 14 similar triangular pieces in the star. Each has an angle Φ = 360°/14 ≈ 25.71°The formula for the area of each triangle is given below. We know the area we need to make each triangle, and we know the angle. So, if we know r1, then we can calculate the value that r2 will need to be to preserve the area. Finally, using the cosine rule, we can determine the length of edge of the star.|

Finally, using the cosine rule, we can determine the length of edge of the star.| |

|

The formula for the area of each triangle is given below. We know the area we need to make each triangle, and we know the angle. So, if we know r1, then we can calculate the value that r2 will need to be to preserve the area.

Finally, using the cosine rule, we can determine the length of edge of the star.

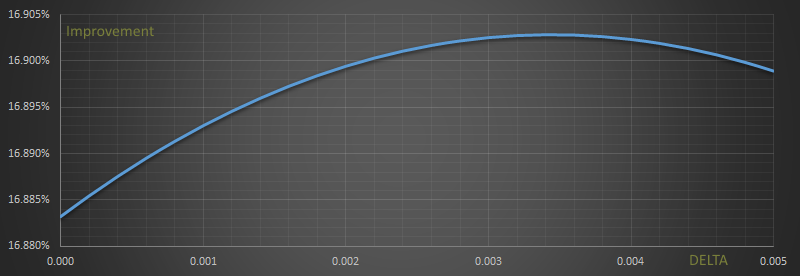

Below is a table generated by displacing the vertices of the heptagon an increasing distance radially outwards. You can see that, initially, as they are displaced outwards, even with buckling the sides and increasing the length (to preserve the area of the center piece), the overall length of cuts decreases. However, a maximum is soon obtained, and further increasing the radius increases the total cut length again.

In the table below, the delta column is the amount (in units) that that each of the vertices is displaced outwards (radially). r1 is the value of this radius of this vertex, and r2 is the value that the midpoint vertex needs to be to preserve the area. Edge is the length of the outside edge of the triangle (t) and the total column measures the entire lengths of all the cuts needed. As before, the percentage column shows the improvement over the basic sector cut.

| delta | r1 | r2 | Edge | Total Cut | Percent | —— |

| 0.000000 | 0.378826 | 0.341310 | 0.164366 | 6.649348 | 16.8831% | |

| 0.000200 | 0.379026 | 0.341130 | 0.164454 | 6.649169 | 16.8854% | |

| 0.000400 | 0.379226 | 0.340950 | 0.164542 | 6.649000 | 16.8875% | |

| 0.000600 | 0.379426 | 0.340770 | 0.164630 | 6.648842 | 16.8895% | |

| 0.000800 | 0.379626 | 0.340590 | 0.164720 | 6.648696 | 16.8913% | |

| 0.001000 | 0.379826 | 0.340411 | 0.164810 | 6.648560 | 16.8930% | |

| 0.001200 | 0.380026 | 0.340232 | 0.164901 | 6.648435 | 16.8946% | |

| 0.001400 | 0.380226 | 0.340053 | 0.164993 | 6.648321 | 16.8960% | |

| 0.001600 | 0.380426 | 0.339874 | 0.165086 | 6.648218 | 16.8973% | |

| 0.001800 | 0.380626 | 0.339696 | 0.165179 | 6.648126 | 16.8984% | |

| 0.002000 | 0.380826 | 0.339517 | 0.165273 | 6.648044 | 16.8994% | |

| 0.002200 | 0.381026 | 0.339339 | 0.165368 | 6.647974 | 16.9003% | |

| 0.002400 | 0.381226 | 0.339161 | 0.165464 | 6.647913 | 16.9011% | |

| 0.002600 | 0.381426 | 0.338983 | 0.165560 | 6.647864 | 16.9017% | |

| 0.002800 | 0.381626 | 0.338806 | 0.165658 | 6.647825 | 16.9022% | |

| 0.003000 | 0.381826 | 0.338628 | 0.165756 | 6.647796 | 16.9025% | |

| 0.003200 | 0.382026 | 0.338451 | 0.165854 | 6.647778 | 16.9028% | |

| 0.003400 | 0.382226 | 0.338274 | 0.165954 | 6.647771 | 16.9029% | |

| 0.003600 | 0.382426 | 0.338097 | 0.166054 | 6.647774 | 16.9028% | |

| 0.003800 | 0.382626 | 0.337920 | 0.166155 | 6.647788 | 16.9027% | |

| 0.004000 | 0.382826 | 0.337744 | 0.166257 | 6.647812 | 16.9024% | |

| 0.004200 | 0.383026 | 0.337567 | 0.166359 | 6.647846 | 16.9019% | |

| 0.004400 | 0.383226 | 0.337391 | 0.166462 | 6.647890 | 16.9014% | |

| 0.004600 | 0.383426 | 0.337215 | 0.166566 | 6.647945 | 16.9007% | |

| 0.004800 | 0.383626 | 0.337039 | 0.166671 | 6.648010 | 16.8999% | |

| 0.005000 | 0.383826 | 0.336864 | 0.166776 | 6.648086 | 16.8989% |

A maximum of ≈ 16.9029% improvement can be obtained by the addition of an additional vertex at the midpoint of each side. A graph of this data is show below. It’s a small change (less than 1% increase in the length of r1).

This small improvement came about through the additional of just a single mid-point vertex in the edge of the heptagon. If we placed additional vertices in the edges we could make incrementally smaller and smaller improvements as the edge of the heptgaon transformed from having straight sides to gently bowed curves. (It would actually be a fun exercise to attempt to model this as a series of springs to see the shape of the curve, holding in ‘pressure’ of the areas they contained).

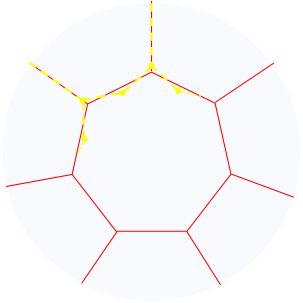

Closer to the Steiner Tree

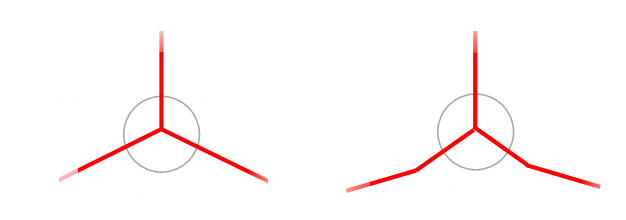

In the basic heptagon solution, the angles at the triple points are shown below on the left. The internal angle of the heptagon is ≈ 128.57° With the addition of the mid-point vertices, the internal angle relaxes to ≈ 124.36°

As additional vertices are added, forming the curve as described above, the internal angles will get closer and closer to the 120° angles predicted by Steiner trees.

You can find a complete list of all the articles here. Click here to receive email alerts on new articles.

Click here to receive email alerts on new articles.