· Read in 9 minutes · 1813 words · All posts in series ·

She pined in thought,

And with a green and yellow melancholy

She sat like Patience on a monument,

Smiling at grief. Was not this love indeed?

[King Lear, Act 2, Scene 4, Line 117]

In King Lear, Shakespeare stirs a sense of self-consciousness by invoking Patience, sitting up high; isolated in her thoughts; pining; reflecting in silence. It is this self-reflection and self-doubt, something we have all experienced, that is the object of this essay. The artwork by Penny Siopsis below makes this tangible: Patience is surrounded by the ‘debris of civilisation’, contemplating the events and actions that led her to this place. We sense she is deep in thought, and we hope, about to enact a profound change in her world.

Like Patience, we too possess this extraordinary ability for reflection and self-evaluation of our thoughts and decisions. Each day we judge our past actions and their correctness, we reflect on our memories and attitudes, and we think through our future actions and the uncertainty of their outcomes. These types of thinking are secondary-levels of thinking: a thinking about thinking. And what is referred to as metacognition.

Patience on a Monument: ‘A History Painting’, Penny Siopsis, 1988.

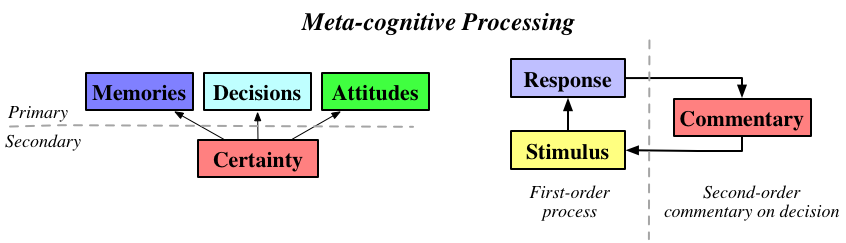

We can form a conceptual understanding of the different types of thoughts using the hierarchy of colours. Like the primary colours, our primary thoughts are those that are the basis of our cognition. They involve perception, recognition, associative learning, and learning from reward. Primary thinking is about direct or object-level thinking. Secondary colours use the primary colours as their basis, and similarly, secondary thoughts are thoughts about our primary thoughts. Secondary thinking is a meta-thinking and are reflections on the object level.

Secondary-thinking, or metacognition, affects the ways in which we form judgements about the world, and our judgements in turn affect our behaviour. This makes metacognitive processing a core component of human decision-making. Which leads us back to Patience and her life of self-reflection, of metacognitive living.

Metacognition is the theory of secondary thoughts—of self-evaluation and monitoring of primary thoughts—and importantly the mechanisms people have for evaluating uncertainty and confidence in their decisions.

(Left) Distinction between primary and secondary thoughts. (Right) Basic model of metacognition.

Metacognition was a new word when first used by John Flavell while exploring the memory abilities of children [1]. He defined metacognition, and still its definition today, as the ‘knowledge and cognition about cognitive phenomena’. This cognition includes the awareness, introspection and control of thoughts. Metacognition is often considered to be one of our most sophisticated of cognitive capacities.

Nelson and Narens [2] provided the canvas upon which our modern understanding of metacognition has been painted, using three abstract principles:

-

There are two distinct levels of cognitive processes, an object level (of perception and recognition) and a meta level.

-

The meta level consists of a dynamic model, e.g., a mental simulation of the object level or an intuitive theory.

-

There are two distinct directions of information flow, control (meta to object level) and monitoring (object to meta level).

Dunlosky and Metcalfe [3] added colour to this canvas by delineating three types of metacognitions: metacognitive knowledge, which is the knowledge we have about our own cognitive strengths and limitations; monitoring, the ongoing self-evaluation of our thoughts; and control, the regulation of our thoughts and the ability to revisit and revise our goals. And our philosophical understanding of these metacognitions was expanded through the concepts of noetic, autonoetic, and anoetic awareness by Metcalfe and Son.

Our memories, decisions and attitudesare amongst our primary thoughts, and for each we have secondary thoughts—metacognitive confidence assessments—that guide our behaviours.

**Metacognitive confidence in memory. **

-

If you were to be asked, you would be able to evaluate how confident you are in using your memories. Tulving and Madigan expressed the wonder of such a feat: it is one of the ’truly unique characteristics of human memory; its knowledge of its own knowledge’.

-

We make judgements in two ways: about how well we will be able to remember an upcoming event (‘will I be able to learn a new language?’) and how well we can remember a past event (‘did I switch the lights off?’).

-

Like memories, we can make confidence assessments about our decision-making.And with these confidence assessments we are able to monitor errors we make as we do a task, form long-term plans, and learn from past experience to improve our future performance.

-

Again, we can make such assessments in two ways: about the decisions we are still to make, a prospective *decision confidence; and decisions we have already made, a retrospective* decision confidence.

-

We hold our attitudes with varying degrees of belief and have the metacognitive ability to inspect our attitudes and the strength of our beliefs.The uncertainty with which we hold our beliefs has a strong impact on our decision making, since attitudes held with more certainty are more resistant to change, stable over time and more predictive of behaviour than those that are less uncertain.

A large body of evidence for metacognition comes from studies of the metacognitive abilities of children. Children as young as 3-5 years old exhibit both verbal and non-verbal metacognitive behaviours during problem solving; by the age of 4 children are able to theorise about their own thinking; children as young as 6 can reflect with accuracy on their cognition, with grade-1 students being able to evaluate the plausibility of their science conceptions. In neuroscience, there is an increasing understanding of the neural basis of metacognition [4]: retrospective decision certainty has been explored in rats (Kepecs et al, 2008), decision confidence studied using single neuron recordings in rhesus monkeys (Kiani and Shadlen, 2009), and by many studies in perceptual choice tasks (Yeung and Summerfield, 2012).

Our understanding is continually improving, and these papers provide an introduction:

And so we return to Patience, sitting up high. Her state of mind is what led our cognitive observation that metacognition, peoples ability to internally audit their thoughts and confidence, is a critical component of human cognition. This is supported by a continually growing body of evidence from neuroscience, cognitive psychology, and philosophy of mind. Uncertainty monitoring influences all our thoughts: what and how we remember, how and when we act, and even the degree and flexibility of our beliefs. Our human learning system would be incomplete without such metacognitions. It is this realisation that provides the cognitive inspiration for machine-learning systems.

In machine learning, we are able to represent uncertainty at any and all levels of our systems: uncertainty in the input data, in what parameters we use to make predictions, in any predictions we make, over the structure of our models, over how we obtain our training data, and even over the types of algorithms we use. Uncertainty appears in many forms, and when we can gain certainty by accumulating more data, we call this reducible uncertainty, and where there is an inherent level of randomness that cannot be removed, this is an irreducible uncertainty [5].

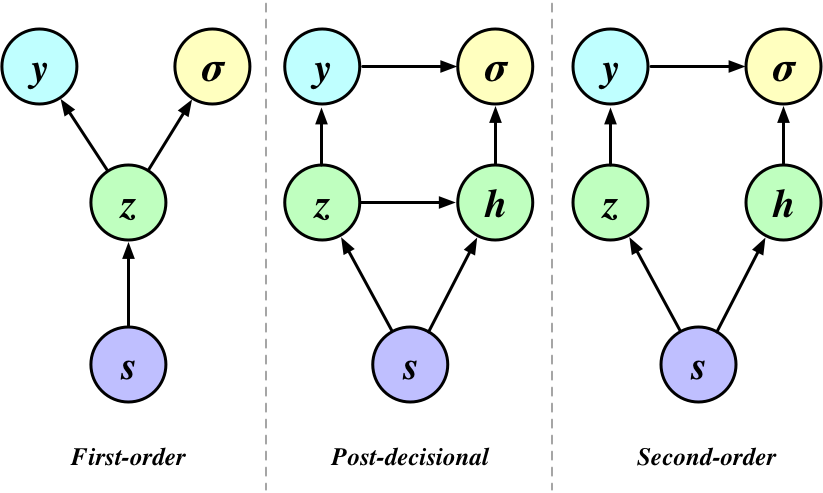

Three models for assessing decision-confidence. Decision y, stimulus s, hidden states z, h, and confidence σ. From Fleming and Daw (2017).

Fleming and Daw (2017) [6] develop probabilistic models to aid our understanding of metacognition. The left model in the figure above is a common pattern, in which a decision y is coupled with the uncertainty σ about that decision by a shared latent source. This is a model that describes the operation of primary thoughts and first-order processing; the default approach to graphical modelling often follows this route. The centre model has uncertainty informed by the decision y, but is also informed by other hidden variables in the model. The right model takes us closer to a desired metacognitive model, since it does not have access to internal information, instead acting as an independent verifier of the decision outcome y.

A deeper understanding of uncertainty quantification can be gained by studying the areas where is it is actively developed. These areas and useful references are:

Bayesian analysis. The Bayesian statistical thinking emphasises that all aspects of a model are probability distributions rather than single estimates. Because entire probability distributions are maintained, uncertainty can always be accounted for and used. The approach of Fleming in Daw is in this school, and additionally points out the importance of choosing an appropriate model structure.

- Reasoning about uncertainty, by David Halpern is a book with a broad overview of all aspects of uncertainty, the different mathematical tools we have available and the connections between them.

An inevitable question arises: what role does metacognition play in consciousness? This is a fascinating question on which much has been written, although consciousness remains one of the foggiest topics in cognitive science. But this question is useful to us. It emphasises the importance of metacognition and self-evaluation in decision-making, strengthens the need for probabilistic reasoning in brains and machines, and further motivates our efforts in building a deeper understanding of the principles of uncertainty, of which much is left to do.

Complement this essay by reading the other essays in this series, a neuroscience-inspired series of essays on learning in brains and machines, and a post of the language of modelling on the question of ‘what is deep?’.

Some References

Related