||

There’s probably a good chance that you’ve used the three most commonly studied trig functions:

Sine, Cosine, and Tangent.

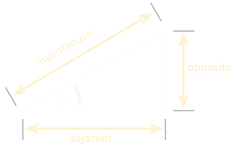

Etymologically, the word Sine is derived from the ancient Sanskrit word for chord, and is used to represent the ratio of the opposite side to the hypotenuse in a right angle triangle. The Cosine is the ratio of the adjacent to the hypotenuse, and the Tangent is the ratio of the opposite side to the adjacent.

The Sine and Cosine functions are closely related; they are similar, simply being phase translated 90° (π/2 radians).

In addition to the three common trig functions, you might have also been taught about their reciprocals:

Secant, Cosecant, and Cotangent.

-

Sine is opposite over hypotenuse, and Cosecant is hypotenuse over opposite.

-

Cosine is adjacent over hypotenuse, and Secant is hypotenuse over adjacent.

-

Tangent is opposite over adjacent, and Cotangent is adjacent over opposite.

There are, however, whole families of additional trig functions you might never have heard about. These include:

Versine, Vercosine, Coversine, Covercosine, Exsecant, Excosecant, Haversince, Havercosine, Hacoversine, Hacovercosine.

Wait, what? What are all these?

Don’t freak out; they do not represent a whole section of mathematics you missed out from at school. They are simply friendly names for basic combinations of the basic three trig functions. Here are their identities:

| Function | Identity | —— |

| versin(θ) | 1–cos(θ) | |

| vercosin(θ) | 1+cos(θ) | |

| coversin(θ) | 1–sin(θ) | |

| covercosin(θ) | 1+sin(θ) | |

| haversin(θ) | versin(θ)/2 | |

| havercosin(θ) | vercosin(θ)/2 | |

| hacoversin(θ) | coversin(θ)/2 | |

| hacovercosin(θ) | covercosin(θ)/2 | |

| exsec(θ) | sec(θ)–1 | |

| excsc(θ) | csc(θ)–1 |

Animation

That’s a lot of functions you’ve probably never heard of. What do they represent?

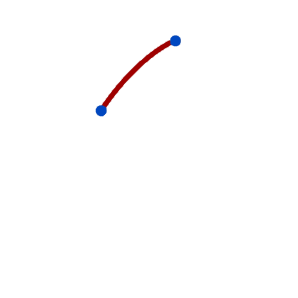

Below are the various trig functions (with the exception of the haver functions) shown on a unit circle to demonstrate their relationships. Use your mouse, or finger, to move the radius around circle. The angle from the horizontal (in radians) is shown in the upper left corner.

The buttons on the right allow you to toggle display of the various trig ratios (and also if they are labelled and their values displayed). The top button turns on/off the hair lines through the origin. The second button toggles if the trig function is labelled on the display. The third button toggles if the numeric values are shown (scaled to unit circle). The lower ten buttons toggle the display of the various trig functions. A colour legend appears to the right of each, when enabled, to key it to the display. With a little experimentation you can see the relationship between these values.

Why?

After a while, you might ask yourself the question why? Why do we need all these fancy named functions when they are all so closely related to the basic trig functions? What value do they add?

It all comes down to efficiency, and a time before electronic computers and calculators. Before electronic aids, calculations had to be performed by hand, and any option to remove complexity would speed things up and reduce the risk of error.

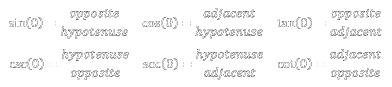

Addition and subtraction is much easier than multiplication or division when dealing with multiple digit numbers. Once upon a time, complex multiplications were performed using logarithms. (I’m probably dating myself, but when I took my mathematics exams at school I had to use log tables*)

*I also learend how to use a slide-ruler, but never had to use one in exams!

Any multiplication problem can be turned into an addition problem because of the principle below:

logb(m × n) = logbm + logbn

A few decades ago, to multiply two numbers together, you would use a table of pre-computed logarithms (available as books at the desired level of precission) to find the logs of these numbers, then add these, then look up the sum in an antilog table to convert it back (find out which number has that log).

These log table books would also contain pre-computed tables of the standard trig functions.

Each math operation required time, and introduced the chance of error. To help reduce the number of operations needed, pre-computing tables for trig functions in a variety of ways to reduce the number of operations necessary could reduce steps. Also, as we will see below the Versine family of trig functions range between 0 and 2, and not from -1 to 1 that the standard trig functions use (which simplifies not having to deal with negative numbers; undefined for log functions!)

Many log table books would contain tables for these ‘fancy’ trig functions. If you need to calculate the sine of a number as an intermediate step, that you then regularly have to perform the same calculation on this result, why no pre-compute this value and store it in a look-up table and save an intermediate step? This saves time, resources, and reduces the chance of error.

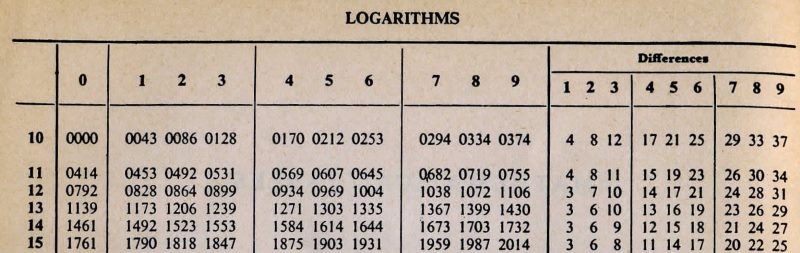

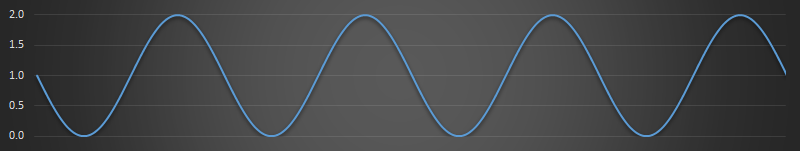

Here’s a graph of the Sin function from -4π to +4π. You can see how it oscilates around +/- 1:

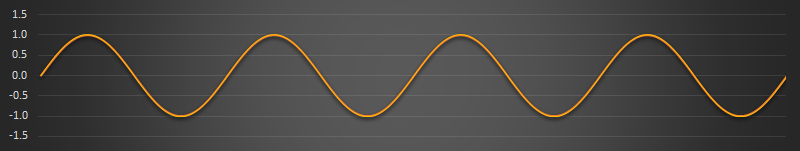

Below is a graph of the Coversin function (1-sin) of the same range. You can see how this oscilates between zero and two:

Haversine Formula

| |The haversine tables were exceptionally useful to navigators and early pioneers traversing the globe. They were used to simplify the number of steps required to calculate the distances between pairs of coordinates (given their latitudes and longitudes).The first table of haversines in English was published by James Andrew in 1805, but Florian Cajori credits an earlier use by José de Mendoza y Ríos in 1801.The great circle distance between two points on a sphere of radius (r), based on their latitudes (ψ) and longitudes (γ), is given by the formula below.The is called the Haversine Formula.|

|The haversine tables were exceptionally useful to navigators and early pioneers traversing the globe. They were used to simplify the number of steps required to calculate the distances between pairs of coordinates (given their latitudes and longitudes).The first table of haversines in English was published by James Andrew in 1805, but Florian Cajori credits an earlier use by José de Mendoza y Ríos in 1801.The great circle distance between two points on a sphere of radius (r), based on their latitudes (ψ) and longitudes (γ), is given by the formula below.The is called the Haversine Formula.|

The first table of haversines in English was published by James Andrew in 1805, but Florian Cajori credits an earlier use by José de Mendoza y Ríos in 1801.

The is called the Haversine Formula.

You can see how this leverages the haversine trig function and how tables of these would enable calculations quicker.

You can find a complete list of all the articles here. Click here to receive email alerts on new articles.

Click here to receive email alerts on new articles.