||

| |In the TV game show “The Price is Right”, contestants who win individual games advance, in groups of three, to compete in another game called “The Big Wheel”. The winner of this game advances to the “Showcase Showdown” where there is a chance to win very large prizes.|

|

|In the TV game show “The Price is Right”, contestants who win individual games advance, in groups of three, to compete in another game called “The Big Wheel”. The winner of this game advances to the “Showcase Showdown” where there is a chance to win very large prizes.|

| |The Big wheel is similar to a roulette wheel, but mounted on its edge. The wheel contains 20 sections showing cash values from $0.05 to $1.00 in 5¢ increments. Contestants spin the wheel with the aim of getting as close to $1.00 as possible (without going over). At the end of their first spin, they are given the option of spinning again. If they spin a second time, the value obtained on the second spin is added to that first spin, and this is their total. There is no option to spin more than twice.Each contestant goes to the wheel and spins (once or twice). The player who gets closest to $1.00, without going over, advances to the “Showcase Showdown”.In the event of a winning tie score, the tied players spin again (one spin only Vasily), as a tie-break to determine the winner (repeating the process, if necessary). This is called a “Spin off”|

|The Big wheel is similar to a roulette wheel, but mounted on its edge. The wheel contains 20 sections showing cash values from $0.05 to $1.00 in 5¢ increments. Contestants spin the wheel with the aim of getting as close to $1.00 as possible (without going over). At the end of their first spin, they are given the option of spinning again. If they spin a second time, the value obtained on the second spin is added to that first spin, and this is their total. There is no option to spin more than twice.Each contestant goes to the wheel and spins (once or twice). The player who gets closest to $1.00, without going over, advances to the “Showcase Showdown”.In the event of a winning tie score, the tied players spin again (one spin only Vasily), as a tie-break to determine the winner (repeating the process, if necessary). This is called a “Spin off”|

Each contestant goes to the wheel and spins (once or twice). The player who gets closest to $1.00, without going over, advances to the “Showcase Showdown”.

There is also a bonus payout if any player spins exactly $1.00 on either one or two spins. I’m going to ignore this fact in my analysis under the understanding that the potential monetary value of the showcase showdown is significantly higher than the bonus prize. Explicitly: if a player is in a winning position, but with a score of less than $1.00, they would not spin again to risk busting, on the off chance they would score exactly $1.00 to claim the additional bonus.

Here is the sequence of how the numbers appear on the wheel. They are distributed fairly randomly around the wheel. If the numbers were clustered, or arranged in descending order, then a skillful player could attempt to gauge just how hard to spin the wheel to land in a cluster of low scoring numbers and minimize the chance of busting.

10 45 70 25 90 5 100 15 80 35 60 20 40 75 55 95 50 85 30 65

There’s at least $0.20 difference between any two adjacent numbers on the wheel.

| StrategyWhat is the optimal strategy? Should a player spin more than once?Clearly, if they spin a second time, there’s a chance that they are going to bust, but is this risk worth it?|

StrategyWhat is the optimal strategy? Should a player spin more than once?Clearly, if they spin a second time, there’s a chance that they are going to bust, but is this risk worth it?| |

|

Clearly, if they spin a second time, there’s a chance that they are going to bust, but is this risk worth it?

Two person game

Let’s simplify the game to make it easier to analyze. Let’s imagine there are just two players, not three.

To understand the optimal strategy for each player, we work in reverse order.

Second player strategy

| |The strategy of the second player is pretty simple. In fact, there is no real decision to make. The second player simply spins until he beats the first player, or busts, that’s it! It’s an advantage to go second as you already know the target you have to beat. You never have to decide “Is my score good enough?”If, on their first spin, the second player beats the first player’s score, they stop, having won.If they spin a score lower than the first player, they spin again, irrespective of what their first spin was. They have nothing to lose! Not spinning again is an instant loss. Spinning again, even when there is a high risk of busting, is the only way they stand a chance of winning.|

|The strategy of the second player is pretty simple. In fact, there is no real decision to make. The second player simply spins until he beats the first player, or busts, that’s it! It’s an advantage to go second as you already know the target you have to beat. You never have to decide “Is my score good enough?”If, on their first spin, the second player beats the first player’s score, they stop, having won.If they spin a score lower than the first player, they spin again, irrespective of what their first spin was. They have nothing to lose! Not spinning again is an instant loss. Spinning again, even when there is a high risk of busting, is the only way they stand a chance of winning.|

If, on their first spin, the second player beats the first player’s score, they stop, having won.

What happens if there is a tie? If there is a tie on the second spin, it’s a push, and it goes to a spin-off. A slightly trickier situation is what to do if there is a tie on the first spin: Should the second player bank the tie and force a spin-off (for which there is a 50:50 chance of a win), or risk a second spin to win outright? This depends on the value of the tie. Anything less than $0.50, and it’s more advantageous to spin again (you have better than 50:50 of not busting on a second spin, c.f. a 50:50 chance on a spin-off).

We can see clearly that the second player has the advantage. The strategy is also simple: spin again if you’ve not won. In the event of a tie, spin again if you have less than $0.50.

What is the optimal strategy for the first player? What should his strategy be to maximize his chances of winning?

First player strategy

| |The optimal strategy for the first player is more complex. The first player has to decide, “Is my score good enough?” at the end of their first spin. Should they bank, or spin again? They need to decide this based on the fact that the second player will automatically go for bust/win with no regrets.The key question is should the first player take another spin and, of course, the answer to this depends on what the first spin was. If the first spin is low, he will spin again. Alternatively, if the first spin is high, he will bank, and not risk busting. How high is sufficient to bank, knowing that the second player has nothing to lose when they spin?|

|The optimal strategy for the first player is more complex. The first player has to decide, “Is my score good enough?” at the end of their first spin. Should they bank, or spin again? They need to decide this based on the fact that the second player will automatically go for bust/win with no regrets.The key question is should the first player take another spin and, of course, the answer to this depends on what the first spin was. If the first spin is low, he will spin again. Alternatively, if the first spin is high, he will bank, and not risk busting. How high is sufficient to bank, knowing that the second player has nothing to lose when they spin?|

The key question is should the first player take another spin and, of course, the answer to this depends on what the first spin was. If the first spin is low, he will spin again. Alternatively, if the first spin is high, he will bank, and not risk busting. How high is sufficient to bank, knowing that the second player has nothing to lose when they spin?

“Is my score good enough?”

To determine this answer we have to work out two probabilities:

-

The probability that, if he stands, the first player’s current score will win.

-

The probability that, if he spins again, the new score will win (understanding there is also a chance of busting).

After calculating these two probabilities, the player should take the action of the highest probability. These probabilities depend on the value of the first spin and, as we will see, there will be a value where these two probabilities cross over and we can condense the optimal strategy down to a simple stopping rule.

That is the theory, now let’s crunch the numbers …

Analysis

There are a variety of techniques we can use to calculate these two probabilities, and in the interests of diversity, I’ll show two different deterministic ways. (Another possible way to calculate the optimal strategy would be to simple use a Monte-Carlo simulation to model the game. It’s not a complex system and a with a reasonable random number generator, and a couple of hundred thousand ‘spins’, a fairly accurate simulation can be obtained. For each possible stopping condition, a plurality of trials could be run, and the stopping condition that results on the best odds would be the optimal strategy).

Player one always sticking

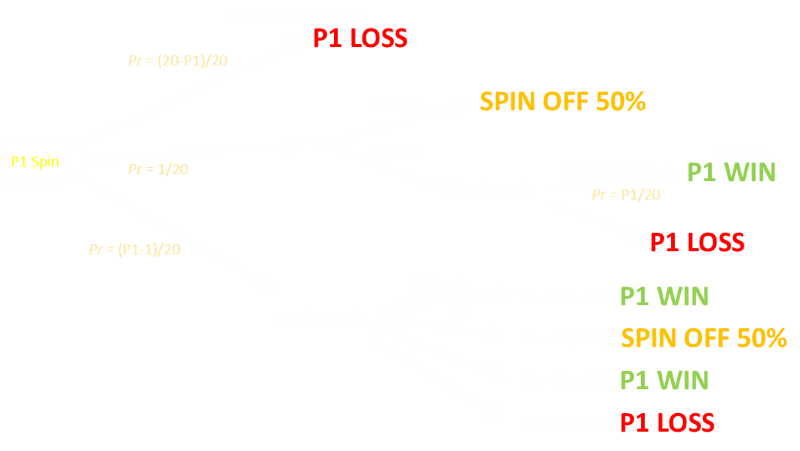

We’ll first calculate the odds of the first player winning if they stick with their first spin, irrespective of what that spin is. Let’s draw a tree diagram to see all that could happen. To simplify the numbers, we’ll convert the prices from $0.05 – $1.00 to numbers 1–20, by dividing by 5¢ (so $0.05 corresponds to 1, and $1.00 corresponds to 20).

It looks a little complicated, but it’s not really that bad. Let’s examine things from the left. Player 1 has just spun, and we’re modelling what happens if he stands, not matter what he obtains. Now the second player spins. Three things could happen:

-

The second player scores higher. This is an instant win for the second player. We know what the first player spun (P1), so we know that the number of prices that beat this (20-P1), and the probability of the second player spinning one of these values is (20-P1)/20.

-

It’s possible that the second player could spin the same score as the first player on a single spin. This occurs one time in twenty. What happens in this tie depends on the value of the tie. If the value of the tie is greater than 10 ($0.50), then it is in the best interest of the second player to bank and force a spin off. A spin off is 50:50 chance, and with a score of higher than 10 it’s more likely than this that the second player will bust if he spins again.

Lastly, there is a chance that the second player’s spin is less than the first player’s. This causes an automatic second spin for the second player, and the sub tree to the lower right. In this sub tree there are four states: Bust, Tie, Win, and Loss.

Let’s use a table to display all this information:

| P1 SPIN | Pr(P2 win) | Pr(Tie) | Pr(roll again) | V(tie) | Pr(Win 2nd spin) | EV(2nd spin) | FINAL | —— |

| ** $0.05 ** | 0.95 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.025 | 0.00250 | |

| ** $0.10 ** | 0.90 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.10 | 0.05 | 0.075 | 0.00875 | |

| ** $0.15 ** | 0.85 | 0.05 | 0.10 | 0.15 | 0.10 | 0.125 | 0.02000 | |

| ** $0.20 ** | 0.80 | 0.05 | 0.15 | 0.20 | 0.15 | 0.175 | 0.03625 | |

| ** $0.25 ** | 0.75 | 0.05 | 0.20 | 0.25 | 0.20 | 0.225 | 0.05750 | |

| ** $0.30 ** | 0.70 | 0.05 | 0.25 | 0.30 | 0.25 | 0.275 | 0.08375 | |

| ** $0.35 ** | 0.65 | 0.05 | 0.30 | 0.35 | 0.30 | 0.325 | 0.11500 | |

| ** $0.40 ** | 0.60 | 0.05 | 0.35 | 0.40 | 0.35 | 0.375 | 0.15125 | |

| ** $0.45 ** | 0.55 | 0.05 | 0.40 | 0.45 | 0.40 | 0.425 | 0.19250 | |

| ** $0.50 ** | 0.50 | 0.05 | 0.45 | 0.50 | 0.45 | 0.475 | 0.23875 | |

| ** $0.55 ** | 0.45 | 0.05 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.525 | 0.28750 | |

| ** $0.60 ** | 0.40 | 0.05 | 0.55 | 0.50 | 0.55 | 0.575 | 0.34125 | |

| ** $0.65 ** | 0.35 | 0.05 | 0.60 | 0.50 | 0.60 | 0.625 | 0.40000 | |

| ** $0.70 ** | 0.30 | 0.05 | 0.65 | 0.50 | 0.65 | 0.675 | 0.46375 | |

| ** $0.75 ** | 0.25 | 0.05 | 0.70 | 0.50 | 0.70 | 0.725 | 0.53250 | |

| ** $0.80 ** | 0.20 | 0.05 | 0.75 | 0.50 | 0.75 | 0.775 | 0.60625 | |

| ** $0.85 ** | 0.15 | 0.05 | 0.80 | 0.50 | 0.80 | 0.825 | 0.68500 | |

| ** $0.90 ** | 0.10 | 0.05 | 0.85 | 0.50 | 0.85 | 0.875 | 0.76875 | |

| ** $0.95 ** | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.90 | 0.50 | 0.90 | 0.925 | 0.85750 | |

| ** $1.00 ** | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.95 | 0.50 | 0.95 | 0.975 | 0.95125 |

The first column in the table above is what the first player rolled. The next three columns show the probabilities of the three cases (Instant P2 win, tie, P2 to roll again without tie). These three probabilities, of course, add up to 1.0

The instant loss to P2 has no value to P1. The next column over shows the value to P1 on a tie. A tie at a value >$0.50 is 0.5. The smaller the P1, the lower the expected chance of a win for P1. This value encapsulates the expected value of either second P2 roll on the current total, or a spin-off at 50:50

The probability that the first player will still be winning after the second roll is, interestingly, the same as the probability that a second roll will happen. This can be visualized by imaginining this as a rolling window. Whatever P2 rolls as their first spin, there are some second spins that will cause a bust, and there are some that will not be sufficient. Combining these, the number of ‘winning’ spaces for the second player does not depend on the value of the first spin from P2.

This is illustrated below. Imagine that P1 rolled $0.25. In the table below, along the top, are all possible values for the second spin, and down the left are the possible values that the second player’s first spin could have been.

As we know that P2 did not instantly win (or tie) there are four possible values that they could have obtained: $0.05, $0.10, $0.15, or $0.20. Each of these is depecited as a row on the table above. For each row there is one possible value that results in a tie (dark red), and four other values that result in a loss for player 2 (either because they will cause a bust, or not be high enough value to secure a win). This illustrates the sliding window that the number of ‘winning’ spin values is agnostic of the first spin of the second player.

The expected value of a second roll is an enacapuslation of a 1/20 chance of a tie (which is worth 0.5 to player one), and probability of a win outright after the second roll.

The final column on the right, in green, shows the expected result based on staying at that P1 value. This is created by adding (logical OR) each of the expected values of the three branches: zero value from an instant loss, plus Pr(tie) × Value(tie), plus Pr(roll again) × EV(2nd roll).

The final values range for a meagre 0.25% (if the first player spun a $0.05 and banked, then the second player also rolled $0.05 and, on his second spin, was unlucky enough to roll a $1.00, and bust out, giving the first player the win = 1/20 × 1/20), through to 95.125% where P1 rolled a $1.00, and so did the second player, and then the first player lost out in a 50:50 spin off (it’s not symmetrical with the $0.05, because there are multiple ways the second player can score $1.00, either from a natural $1.00 on their first spin, or various combinations of two spins that add up to $1.00).

On average, if the first player always stands after their first spin, their expected winning chance, averaged over all values, is just 34%.

Player one always rolling again

We have just calculated the winning chances if P1 always stands. Now let’s calculate the winning chances if P1 always spins again. We could use the same strategy, but let’s look at another way.

Another easy way to calculate the odds is to simply enumerate out all possible combinations of spins. Computers are very good at this. There are 20 possible values for what a the first player’s first spin could be, and 20 possible values for what the first player’s second spin could be, and similary 20 possible values for each of other two second player’s spins. This 20 × 20 × 20 × 20 = 160,000 combinations. Using a computer program, and four nested loops, we can just cycle through each of these, and record the number of times this results in a win for P1, the number of times this results in loss for P1, and the number of times the results in a tie.

| P1 SPIN | # Wins | # Losses | # Ties | Total | FINAL | —— |

| $0.05 | 2514 | 5076 | 410 | 8000 | 0.3398750 | |

| $0.10 | 2511 | 5080 | 409 | 8000 | 0.3394375 | |

| $0.15 | 2504 | 5089 | 407 | 8000 | 0.3384375 | |

| $0.20 | 2491 | 5105 | 404 | 8000 | 0.3366250 | |

| $0.25 | 2470 | 5130 | 400 | 8000 | 0.3337500 | |

| $0.30 | 2439 | 5166 | 395 | 8000 | 0.3295625 | |

| $0.35 | 2396 | 5215 | 389 | 8000 | 0.3238125 | |

| $0.40 | 2339 | 5279 | 382 | 8000 | 0.3162500 | |

| $0.45 | 2266 | 5360 | 374 | 8000 | 0.3066250 | |

| $0.50 | 2185 | 5470 | 345 | 8000 | 0.2946875 | |

| $0.55 | 2085 | 5600 | 315 | 8000 | 0.2803125 | |

| $0.60 | 1964 | 5752 | 284 | 8000 | 0.2632500 | |

| $0.65 | 1820 | 5928 | 252 | 8000 | 0.2432500 | |

| $0.70 | 1651 | 6130 | 219 | 8000 | 0.2200625 | |

| $0.75 | 1455 | 6360 | 185 | 8000 | 0.1934375 | |

| $0.80 | 1230 | 6620 | 150 | 8000 | 0.1631250 | |

| $0.85 | 974 | 6912 | 114 | 8000 | 0.1288750 | |

| $0.90 | 685 | 7238 | 77 | 8000 | 0.0904375 | |

| $0.95 | 361 | 7600 | 39 | 8000 | 0.0475625 | |

| $1.00 | 0 | 8000 | 0 | 8000 | 0.0000000 |

There are a total of 8,000 possible combinations for each initial value of spin of P1. These are shown in the table above. The next three columns show the number that result in a win for P1, those ther result in a loss, and those that result in a tie. The final column shows the total expected result for that row (Wins scoring 1.0, losses scoring 0.0, and ties scoring 0.5).

You can see that spinning again after spinning $1.00 on the first spin is suicide; there is no way this can result in a win or a tie.

(The total average expected return over all numbers is just 24.44% meaning that if you had to play a Russian Roulette version of this game as the first player, only spin once! The reason for this lower percentage is that you don’t get a choice, and can’t capitalize on a knowing you had a high initial score and to bank; the second player still has eyes to gauge best strategy, and if you’ve bust out, they are an instant winner).

Results

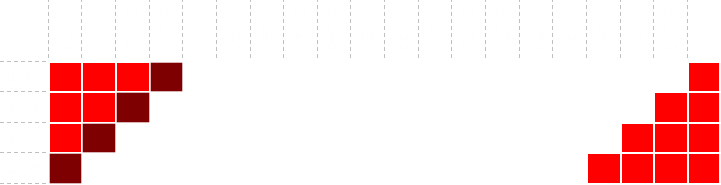

We now have all the data we need. Here are the two results tables combined:

| P1 SPIN | STAND | SPIN | —— |

| $0.05 | 0.0025000 | 0.3398750 | |

| $0.10 | 0.0087500 | 0.3394375 | |

| $0.15 | 0.0200000 | 0.3384375 | |

| $0.20 | 0.0362500 | 0.3366250 | |

| $0.25 | 0.0575000 | 0.3337500 | |

| $0.30 | 0.0837500 | 0.3295625 | |

| $0.35 | 0.1150000 | 0.3238125 | |

| $0.40 | 0.1512500 | 0.3162500 | |

| $0.45 | 0.1925000 | 0.3066250 | |

| $0.50 | 0.2387500 | 0.2946875 | |

| $0.55 | 0.2875000 | 0.2803125 | |

| $0.60 | 0.3412500 | 0.2632500 | |

| $0.65 | 0.4000000 | 0.2432500 | |

| $0.70 | 0.4637500 | 0.2200625 | |

| $0.75 | 0.5325000 | 0.1934375 | |

| $0.80 | 0.6062500 | 0.1631250 | |

| $0.85 | 0.6850000 | 0.1288750 | |

| $0.90 | 0.7687500 | 0.0904375 | |

| $0.95 | 0.8575000 | 0.0475625 | |

| $1.00 | 0.9512500 | 0.0000000 |

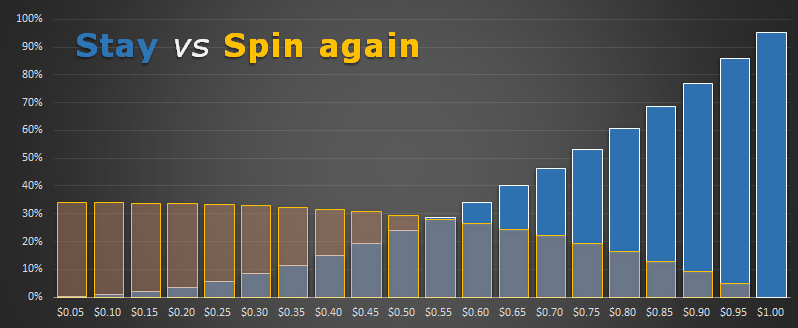

For every possible value for the first spin, we can see the expected result if we stay, or if we spin again. For each situation, we take the higher value. You can see that when the first spin is low, it is advantageous to spin again. When the first spin is high, the best strategy is to stand (no surprise so far). However, what this table does show is where the strategy inverts, and this is at $0.55

On the first spin, if the first player spins $0.55, or higher, he should stand. If he spins lower than $0.55, then he should spin again.

If the first player spins less than $0.55 on his first spin, he should spin again.

This combined strategy improves the first players chance of winning to 45.73%

Here is the data plotted. You can see how the bars cross over at $0.55

Player one’s probability of winning does not pass the 0.5 level until they spin $0.75 or higher, but it is still in their best interest to stop if they score anything above $0.50

Three Players

With quite a bit more work, this analysis can be expanded to work out the optimal strategy when there are three players. Again it’s necessary to work in reverse order and start with the strategy for player 3. It’s further complicated because ties are more involved. In the event you tie, only the players who tie go to spin-off. If player 2 beats player 1 and does not re-spin, then the results of player 1 are irrelevant. Similarly, if either the first or second player busts, the third player only has to worry about one opponent.

There are various papers written about this. Here is one that also discusses the results and compares with the psychological results of what lives players have done To Spin or not to spin, and also bring in the value of the bonus spin.

Here is a summary of each players optimal strategy when there are three players:

-

Player 1 spins again is she gets 65 or fewer points on her first spin.

-

Player 2 spins again if:

-

She spins 50 points of fewer.

-

If she gets 65 or fewer and her score equals that of player 1.

-

If not spinning would guarantee a loss.

-

Player 3 spinds again if:

-

She spins 50 points of fewer, and ties with one other contestant.

-

If she gets 65 or fewer and has ties with both previous contestant.

-

If not spinning would guarantee a loss.

-

She spins 50 points of fewer, and ties with one other contestant.

-

If she gets 65 or fewer and has ties with both previous contestant.

-

If not spinning would guarantee a loss.

Triple Spin Off

| |Hold on to your seats. Here’s a video of, first a three-way tie, then a couple fo two-spin ties.|

|Hold on to your seats. Here’s a video of, first a three-way tie, then a couple fo two-spin ties.|

You can find a complete list of all the articles here. Click here to receive email alerts on new articles.

Click here to receive email alerts on new articles.