· Read in 9 minutes · 1720 words · All posts in series ·

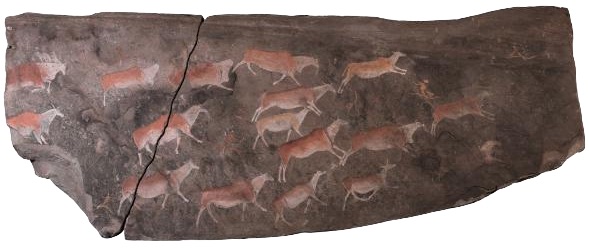

The Zaamenkomst panel. [Iziko Museums]

This is an image of the Zaamenkomst panel: one of the best remaining exemplars of rock art from the San people of Southern Africa. As soon as you see it, you are inevitably herded, like the eland in the scene, through a series of thoughts. Does it have a meaning? Why are the eland running? What do the white lines coming from the mouths of the humans and animals signify? What event is unfolding in this scene? These are questions of interpretation, and of explanation. Explanation is something people actively seek, and can almost effortlessly provide. Having lost their traditional knowledge, the descendants of the San are unable to explain what the scene in the Zaamenkomst panel means. In what ways can machine learning systems be saved from such a fate? For this, we turn to the psychology of explanation, the topic we explore in this post.

Explanation is an omnipresent factor in our reasoning: it guides our actions, influences our interactions with others, and drives our efforts to expand scientific knowledge. Reasoning can be split into its three constituents: deduction, reaching conclusions using consistent and logical premises; induction, the generalisation and prediction of events based on observed evidence and frequency of occurrence; and abduction**, providing the simplest explanation of an event. We don’t often use these words in machine learning, but these concepts are part of our widespread practice: deduction is implied when we use rule-learning, set construction and logic programming; inductive and transductive testing, i.e. making use of test data sets, is our standard protocol in assessing predictive algorithms; and abduction is implied when we discuss probabilistic inference and inverse problems. It is this third type of reasoning,abductive inference,** that in both minds and machines gives us our ability to provide explanations, and to use explanations to learn and act in the future.

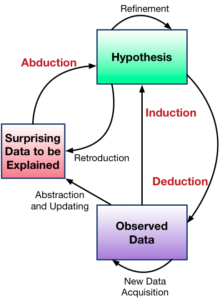

Connections between the different types of reasoning.

Abductive inference is the aspect of reasoning concerned with developing and choosing hypotheses that best explain a situation or data: an emphasis on how explanatory hypotheses are generated, evaluated, tested, and extended [1]. Psychologists often refer to the ability for abduction in people—the ability to spontaneously and effortlessly draw conclusions from our knowledge and experiences—as everyday inference. While seemingly effortless, abduction requires us to engage a multitude of complex cognitive functions, including causal reasoning, mental modelling, categorisation, inductive inference, and metacognitive processing. And in turn, a multitude of cognitive functions depend on our ability to offer explanatory judgements, including plan recognition, diagnosis and theory refinement. It is then not surprising that explanation continues to be active area of research, with many of the most influential ideas in modern psychology being views on explanation and abduction [2].

Let’s sample some of this thinking, beginning with the commonsense psychology or attribution theory of Fritz Heider [3]. The Heiderian view is that we explain events in order to relate them to more general processes. This allows us to obtain a more stable environment, and ultimately, the possibility to control our environment. From this stems the psychology of naive, folk, or intuitive theories [4]. In this framework, we form ‘theories’ of the world that allow us make useful explanatory judgements: again, better explanations leads to better predictions leads to better control. George Kelly recognised explanation as a key part of his personal construct psychology [5] of which an important component is the now famous analogy that we think of ‘man-the-scientist’ rather than ‘man-the-biological-organism’, because of the need to hypothesise, test and explain. The mechanisms of abduction, shown in the flow diagram above, is a basis for scientific explanation and explanatory coherence [6], and is triggered by an initial puzzlement or surprise, leading to a search for explanation, the generation of potential hypotheses, the evaluation of these hypotheses, and finally some satisfaction or conclusion. The role of explanation is supported by several sources of evidence that leaves us with a broad insight:

-

Explanation is commonplace. Povinelli and Dunphy-Lelli (2011) assess the capacity for explanation in chimpanzees; Billargeon (2004) shows the role of explanation in prelinguistic infants; and Keil (in several papers) highlights the role of explanation from children to adults.

-

Explanations are contrastive in that they account for one state of affairs in contrast to another, e.g., Van Fraasen (1980).

-

Explanations are needed for many cognitive functions. Carey (1985) shows its importance for concept learning and categorisation; Holyoak and Cheng (2011) in supporting inductive inference and learning; Chi et al. (1994) in metacognition.

-

There are different types of explanations. Keil (1992) explains that children use ’modes of construal’ whereby they prefer different types of explanations in different situations. One taxonomy is of three types of explanation *(Lombrozo, 2012): *functional, based on goals, intentions or design; mechanistic, explanation using the mechanism and process by which an event arises; and formal, which explains by virtue of membership to a category. Mechanistic and formal explanations are also types of causal explanations.

-

Functional explanations are default. Researchers from Piaget (1929) to Keleman (1999) show that functional explanations are the default, and used more naturally in children.

-

Subjective probability assessments are biased by our explanations. In people, just thinking that an explanation is true is enough to boost its subjective probability of being true, e.g., Koehler (1991).

-

Explanations are limited.We can struggle to detect circular explanations (Rips 2002) and we overestimate the accuracy and depth of our explanations (Rozenblit and Keil, 2002).

This discussion paints a high level view of explanation, and I suggest these sources for more depth:

We began with the cognitive observation that explanation is a central part of human reasoning, and found much evidence for this in animals, infants, children and adults, along with an understanding of the impacts and limitations of our human explanatory powers. In building machines that think and learn, our cognitive inspiration is clear: systems for abductive inference, hypothesis formation and evaluation are essential. These systems help form the basis of our intuitive theories, models of the world, and of our decision making. Fortunately, abduction is not unfamiliar to machine learning.

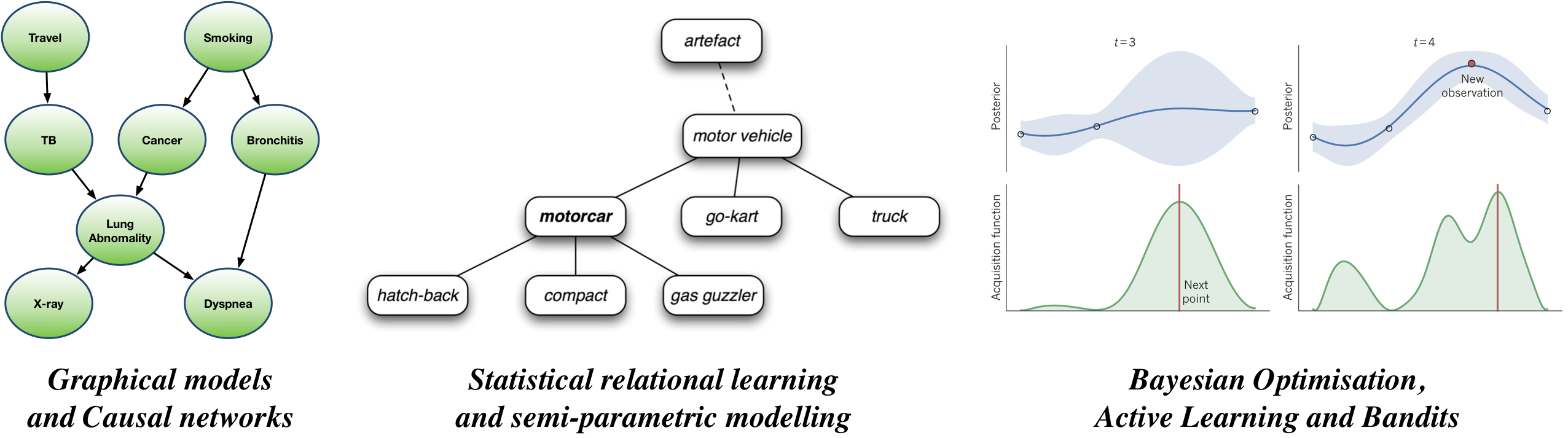

Some machine learning methods related to abductive inference.

Explanation has always been a core topic in machine learning and artificial intelligence. We constantly seek new tools to derive and develop machine learning systems that offer a spectrum of explanations, knowing that different types of explanations are possible; valid or not, we will tend to hold the explanatory requirements of our machine learning systems to a higher standard than we hold ourselves. Learning to explain then becomes a central research question.

Our basic tool with which to incorporate the ideals of ubiquitous explanation and abduction remains, as always, probability. This forms the basis of all types of explanation—functional, mechanistic and formal—in machine learning. Again, it is useful to align our language. An inductive hypothesis is a general theory that explains observations across a wide range of cases: we use the words generalisation and prediction. An abductive hypothesis is an explanation that is related to a specific observation or case: we simply use the word inference, the estimation of unobserved events or probabilities in our models given data [7]. This alignment tells us how the taxonomy of reasoning is related to probabilistic machine learning, and allows us to combine tools from many subject areas. Along with introductory sources, these areas include:

Probabilistic graphical models. We can build models that allow us to capture the ways in which data has been generated, and is a reason to be interested in generative models. Knowing the probability of unobserved variables in such models is the basic unit of explanation: through their inference we can offer explanation, and explanations can be used to improve generalisation.

Causality. A causal explanation is a particularly powerful type of explanation. We can infer the strength of causal effects, and even try to learn the causal structure of events from data.

Relational learning and inductive logic. Formal explanations are based on categorisation and involves learning the relationships between objects, entities, agents, and events in our world. This is a problem of relational learning, a highly active topic in machine learning.

Active learning and Bayesian optimisation. Active and sequential machine learning embodies the role of explanation. One important area is Bayesian optimisation, which allows us to find the best explanation by forming a series of hypotheses and refinements, until reaching a satisfactory conclusion.

Semi-parametric modelling. Cognitive systems need not only be able to make inferences of observations, propose hypotheses, refine and evaluate them, but also be able to extend these hypotheses. This is a hard problem, but the tools of non-parametric modelling lies at our disposal and allows us to extend our models and explanations in a natural and consistent way.

It was recently suggested that forthcoming European regulations create a ‘right to explanation’ when machine learning systems are used in decision making. There are arguments both for and against this suggestion, but policy considerations aside, this emphasises further the importance of explanation and abductive inference in our current practice. The eland in the rock painting are running towards the elusive spirit world. By taking inspiration from cognitive science, and the many other computational sciences, and combining them into our machine learning efforts, we take the positive steps on our own path to the hopefully less elusive world of machine learning with explanations.

Complement this essay with its prelude that contextualises the cognitive architectures that inform these essays, a short discussion on generative models and auto-encoders, and a neuroscience-inspired series of essays on learning in brains and machines.

Some References

Related