Word embeddings are great. They allow us to represent words as distributed vectors, such that semantically and functionally similar words have similar representations. Having similar vectors means these words also behave similarly in the model, which is what we want for good generalisation properties.

However, word embeddings have a couple of weaknesses:

-

If a word doesn’t exist in the training data, we can’t have an embedding for it. Therefore, the best we can do is clump all unseen words together under a single OOV (out-of-vocabulary) token.

-

If a word only occurs a couple of times, the word embedding likely has very poor quality. We simply don’t have enough information to learn how these words behave in different contexts.

-

We can’t properly take advantage of character-level patterns. For example, there is no way to learn that all words ending with -ing are likely to be verbs. The best we can do is learn this for each word separately, but that doesn’t help when faced with new or rare words.

In this post I will look at different ways of extending word embeddings with character-level information, in the context of neural sequence labeling models. You can find more information in the Coling 2016 paper “Attending to characters in neural sequence labeling models“.

Sequence labeling

We’ll investigate word representations in order to improve on the task of sequence labeling. In a sequence labeling setting, a system gets a series of tokens as input and it needs to assign a label to every token. The correct label typically depends on both the context and the token itself. Quite a large number of NLP tasks can be formulated as sequence labeling, for example:

POS-taggingDT NN VBD NNS IN DT DT NN CC DT NN .The pound extended losses against both the dollar and the euro .

Error detection+ + + x + + + + + x +I like to playing the guitar and sing very louder .

Named entity recognitionPER _ _ _ _ ORG ORG _ TIME _Jim bought 300 shares of Acme Corp. in 2006 .

ChunkingB-NP B-PP B-NP I-NP B-VP I-VP I-VP I-VP B-PP B-NP B-NP OService on the line is expected to resume by noon today .

In each of these cases, the model needs to understand how a word is being used in a specific context, and could also take advantage of character-level patterns and morphology.

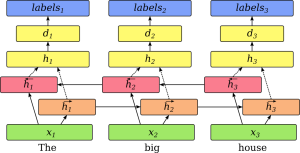

Basic neural sequence labeling

Our baseline model for sequence labeling is as follows. Each word is represented as a 300-dimensional word embedding. This is passed through a bidirectional LSTM with hidden layers of size 200. The representations from both directions are concatenated, in order to get a word representation that is conditioned on the whole sentence. Next, we pass it through a 50-dimensional hidden layer and then an output layer, which can be a softmax or a CRF.

This configuration is based on a combination of my previous work on error detection (Rei and Yannakoudakis, 2016), and the models from Irsoy and Cardie (2014) and Lample et al. (2016).

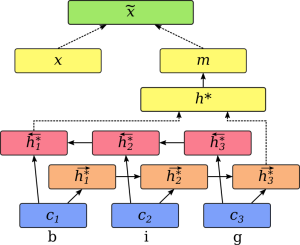

Concatenating character-based word representations

Now let’s look at an architecture that builds word representations from individual characters. We process each word separately and map characters to character embeddings. Next, these are passed through a bidirectional LSTM and the last states from either direction are concatenated. The resulting vector is passed through another feedforward layer, in order to map it to a suitable space and change the vector size as needed. We then have a word representation m, built from individual characters.

We still have a normal word embedding x for each word, and in order to get the best of both worlds, we can combine these two representations. Following Lample et al. (2016), one method is simply concatenating the character-based representation with the word embedding.

(\widetilde{x} = [x; m])

The resulting vector can then be used in the word-level sequence labeling model, instead of the regular word embedding. The whole network is connected together, so that the character-based component is also optimised during training.

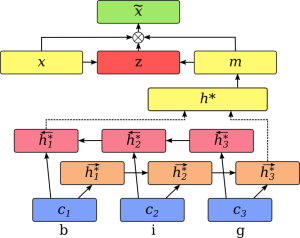

Attending to character-based representations

Concatenating the two representations works, but we can do even better. We start off the same – character embeddings are passed through a bidirectional LSTM to build a word representation m. However, instead of concatenating this vector with the word embedding, we now combine them using dynamically predicted weights.

A vector of weights z is predicted by the model, as a function of x and m. In this case, we use a two-layer feedforward component, with tanh activation in the first layer and sigmoid on the second layer.

(z = \sigma(W^{(3)}z tanh(W^{(1)}{z} x + W^{(2)}_{z} m)))

Then, we combine x and m as a weighted sum, using z as the weights:

(\widetilde{x} = z\cdot x + (1-z) \cdot m)

This operation essentially looks at both word representations and decides, for each feature, whether it wants to take the value from the word embedding or from the character-based representation. Values close to 1 in z indicate higher weight for the word embedding, and values close to 0 assign more importance to the character-based vector.

This combination requires that the two vectors are aligned – each feature position in the character-based representation needs to capture the same properties as that position in the word embedding. In order to encourage this property, we actively optimise for these vectors to be similar, by maximising their cosine similarity:

(\widetilde{E} = E + \sum_{t=1}^{T} g_t (1 – cos(m^{(t)}, x_t)) \hspace{3em}g_t =\begin{cases}0, & \text{if}\ w_t = OOV \1, & \text{otherwise}\end{cases})

E is the main sequence labeling loss function that we minimise during training, T is the length of the sequence or sentence. Many OOV words share the same representation, and we do not want to optimise for this, therefore we use a variable g that limits optimisation only to non-OOV words.

In this setting, the model essentially learns two alternative representations for each word – a regular word embedding and a character-based representation. The word embedding itself is kind of a universal memory – we assign 300 elements to a word, and the model is free to save any information into it, including approximations of character-level information. For frequent words, there is really no reason to think that the character-based representation can offer much additional benefit. However, using word embeddings to save information is very inefficient – each feature needs to be learned and saved for every word separately. Therefore, we hope to get two benefits from including characters into the model:

-

Previously unseen (OOV) words and infrequent words with low-quality embeddings can get extra information from character features and morphemes.

-

The character-based component can act as a highly-generalised model of typical character-level patterns, allowing the word embeddings to act as a memory for storing exceptions to these patterns for each specific word.

While we optimise for the cosine similarity of m and x to be high, we are essentially teaching the model to predict distributional properties based only on character-level patterns and morphology. However, while m is optimised to be similar to x, we implement it in such a way that x is not optimised to be similar to m (using disconnected_grad in Theano). Because word embeddings are more flexible, we want them to store exceptions as opposed to learning more general patterns.

The resulting combined word representation is again plugged directly into the sequence labeling model. All the components, including the attention component for dynamically calculating z, are optimised at the same time.

Evaluation

We evaluated the alternative architectures on 8 different datasets, covering 4 different tasks: NER, POS-tagging, error detection and chunking. See the paper for more detailed results, but here is a summary:

| Dataset | Task | #labels | Measure | Word-based | Char concat | Char attn |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CoNLL00 | chunking | 22 | F1 | 91.23 | 92.35 | 92.67 |

| CoNLL03 | NER | 8 | F1 | 79.86 | 83.37 | 84.09 |

| PTB-POS | POS-tagging | 48 | accuracy | 96.42 | 97.22 | 97.27 |

| FCEPUBLIC | error detection | 2 | F0.5 | 41.24 | 41.27 | 41.88 |

| BC2GM | NER | 3 | F1* | 84.21 | 87.75 | 87.99 |

| CHEMDNER | NER | 3 | F1 | 79.74 | 83.56 | 84.53 |

| JNLPBA | NER | 11 | F1 | 70.75 | 72.24 | 72.70 |

| GENIA-POS | POS-tagging | 42 | accuracy | 97.39 | 98.49 | 98.60 |

As can be seen, including a character-based component into the sequence labeling model helps on every task. In addition, using the attention-based architecture outperforms character concatenation on all benchmarks.

We also compared the number of parameters in each model. While both character-based models require more parameters compared to a basic architecture using only word embeddings, the attention-based architecture is actually more efficient compared to concatenation. If the vectors are simply concatenated, this increases the size of all the weight matrices in the proceeding LSTMs, whereas the attention framework combines them without increasing length.

Miyamoto and Cho (2016) have independently also proposed a similar architecture, with some differences: 1) They focus on the task of language modeling, 2) they predict a scalar weight for combining the representations as opposed to making the decision separately for each element, 3) they do not condition the weights on the character-based representation, and 4) they do not have the component that optimises character-based representations to be similar to the word embeddings.

Since this model is aimed at learning morphological patterns, you might ask why are we not giving actual morphemes as input to the model, instead of starting from individual characters. The reason is that the definition of an informative morpheme is likely to change between tasks and datasets, and this allows the model to learn exactly what it finds most useful. The model for POS tagging can learn to detect specific suffixes, and the model for NER can focus more on capitalisation patterns.

Conclusion

Combining word embeddings with character-based representations makes neural models more powerful and allows us to have better representations for infrequent or unseen words. One option is to concatenate the two representations, treating them as separate sets of useful features. Alternatively, we can optimise them to be similar and combine them using a gating mechanism, essentially allowing the model to choose whether it wants to take each feature from the word embedding of from the character-based representation. We evaluated on 8 different sequence labeling datasets and found that the latter option performed consistently better, even with a fewer number of parameters.

See the paper for more details:https://aclweb.org/anthology/C/C16/C16-1030.pdf

I have made the code for running these experiments publicly available on github:https://github.com/marekrei/sequence-labeler

Also, the dataset for performing error detection as a sequence labeling task is now available online:http://ilexir.co.uk/datasets/index.html