Introduction

Data science continues to generate excitement and yet real-world results can often disappoint business stakeholders. How can we mitigate risk and ensure results match expectations? Working as a technical data scientist at the interface between R and commercial operations has given me an insight into the traps that lie in our path. I present a personal view on the most common failure modes of data science projects.

The long version with slides and explanatory text below. Slides in one pdf here.

There is some discussion at Hacker News

First, about me:

This talk is based on conversations I’ve had with many senior data scientists over the last few years. Many companies seems to go through a pattern of hiring a data science team only for the entire team to quit or be fired around 12 months later. Why is the failure rate so high?

Let’s begin:

A very wise data science consultant told me he always asks if the data has been used before in a project. If not, he adds 6-12 months onto the schedule for data cleansing.

Do a data audit before you begin. Check for missing data, or dirty data. For example, you might find that a database has different transactions stored in dollar and yen amounts, without indicating which was which. This actually happened.

No it isn’t. Data is not a commodity, it needs to be transformed into a product before it’s valuable. Many respondents told me of projects which started without any idea of who their customer is or how they are going to use this “valuable data”. The answer came too late: “nobody” and “they aren’t”

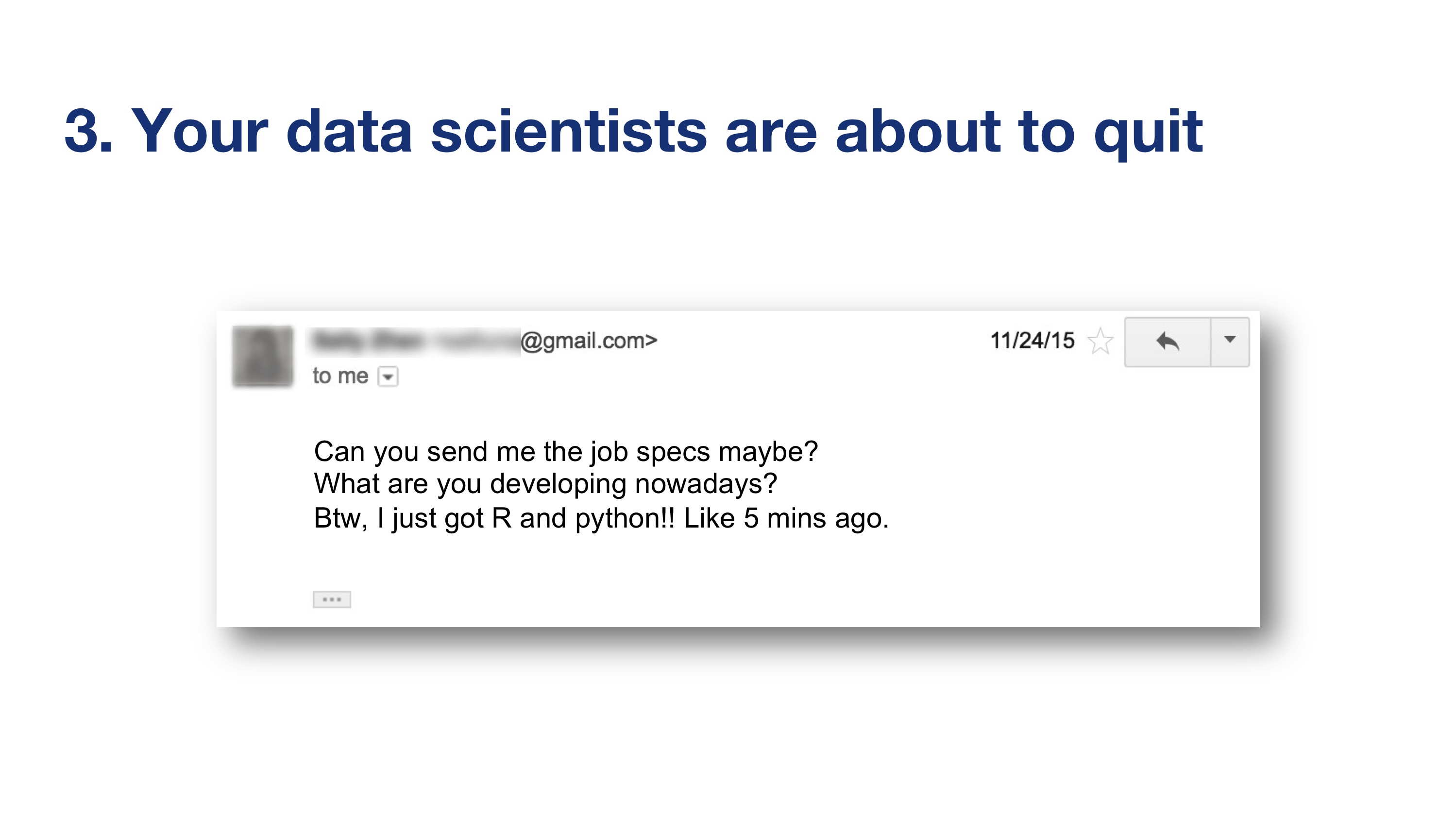

Don’t torture your data scientists by witholding access to the data and tools they need to do their job. This senior data scientist took six weeks to get permission to install python and R. She was so happy!

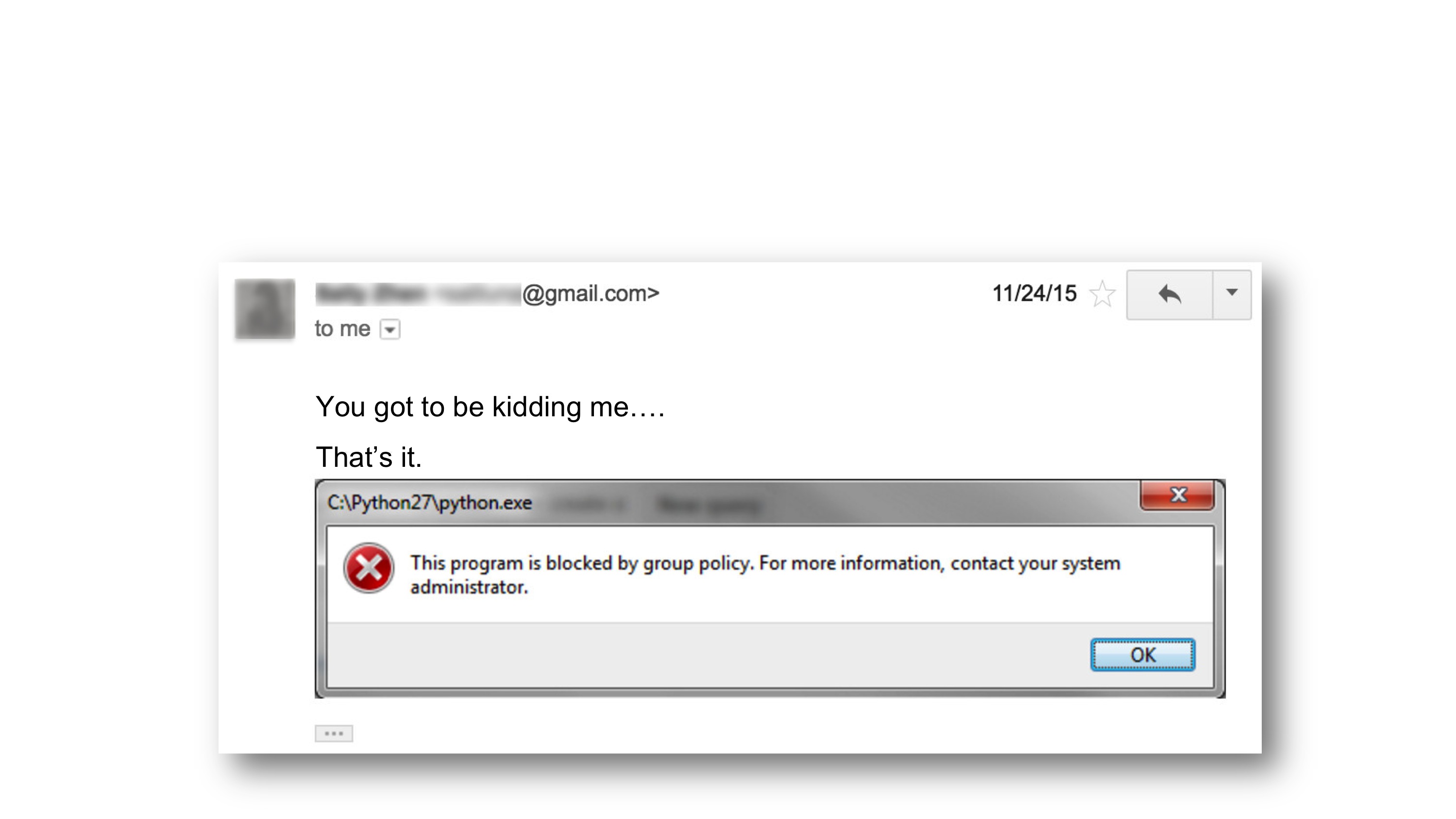

Well, she was until she sent me this shortly afterwards:

Now, allow me to introduce this guy:

He was a product manager at an online auction site that you may have heard of. His story was about an A/B test of a new prototype algorithm for the main product search engine. The test was successful and the new algorithm was moved to production.

Unfortunately, after much time and expense, it was realised that there was a bug in the A/B test code: the prototype had not been used. They had accidentally tested the old algorithm against itself. The results were nonsense.

This was the problem:

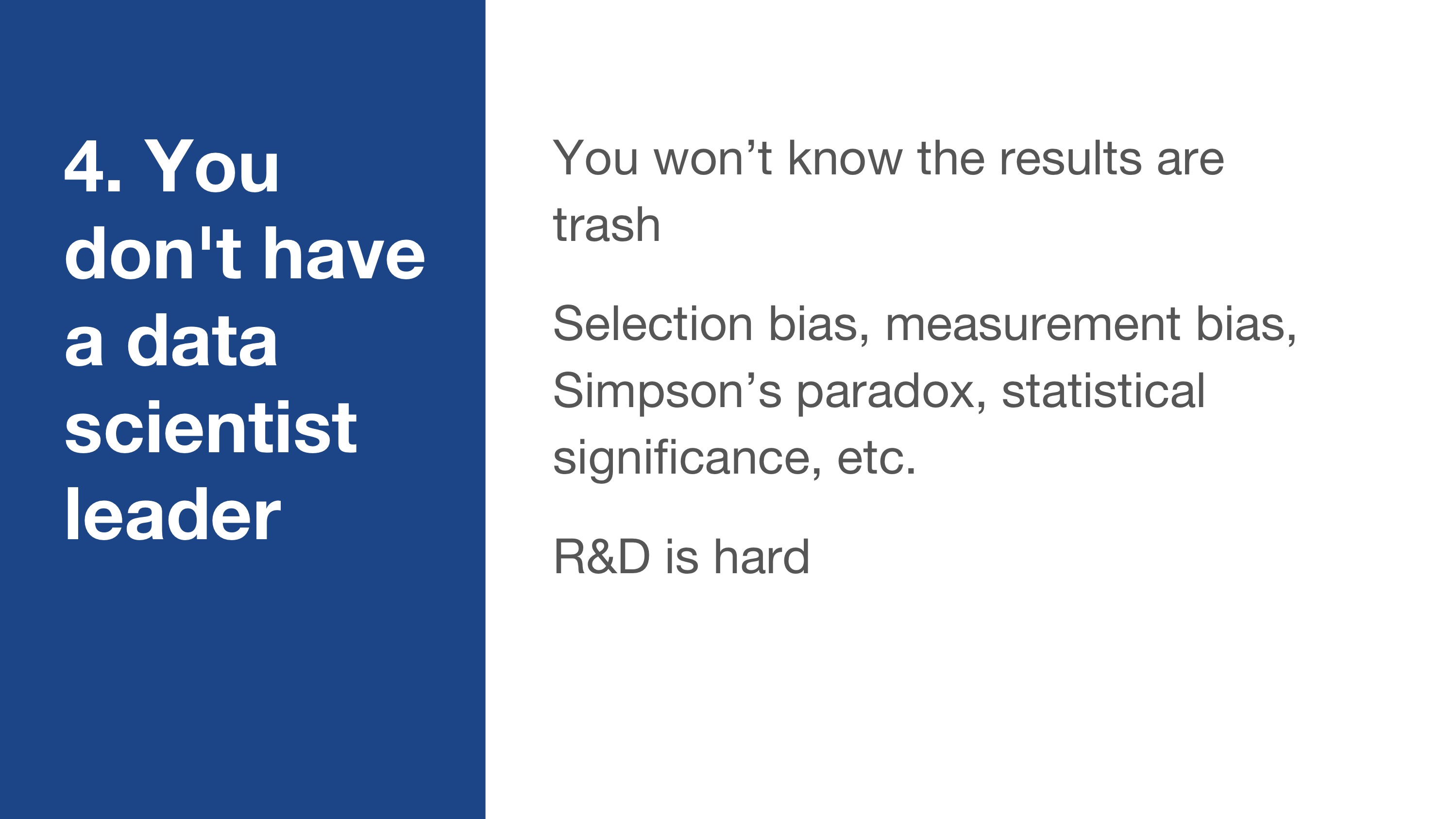

You need people who live and breathe selection bias, measurement bias, etc. or you’ll never know the results are meaningless. These people are called scientists.

Oh, by the way:

Likewise - the opposite is very often true:

The hype around machine learning means there is a lot of readily available content out there. This can lead to the ‘instant expert’ phenomenon: now everyone has a great machine learning idea. Symptoms are your boss using words like ‘regularize’ and ‘ensemble method’ in the wrong context. Trust me, this will not end well.

The Cost-Effective HealthCare project used data from hospitals to process Emergency Room patients who had symptoms of pneumonia. They aimed to build a system that could predict people who had a low probability of death, so they could be simply sent home with antibiotics. This would allow care to be focused on the most serious cases, who were likely to suffer complicatations.

The neural network they developed had a very high accuracy but, strangely, it always decided to send asthma sufferers home. Weird, since asthmatics are actually at high risk of complications from pneumonia.

It turned out that asthmatics who present with pneumonia are always admitted to Intensive Care. Because of this, there were no cases of any asthmatics dying in the training data. The model concluded that asthmatics were low risk, when the opposite was actually true. The model had great accuracy but if deployed in production it would certainly have killed people.

Moral of the story: use a simple model you can understand [1]. Only then move onto something more complex, and only if you need to.

The core of science is reproducibility. Please do all of these things. Don’t say I didn’t warn you.

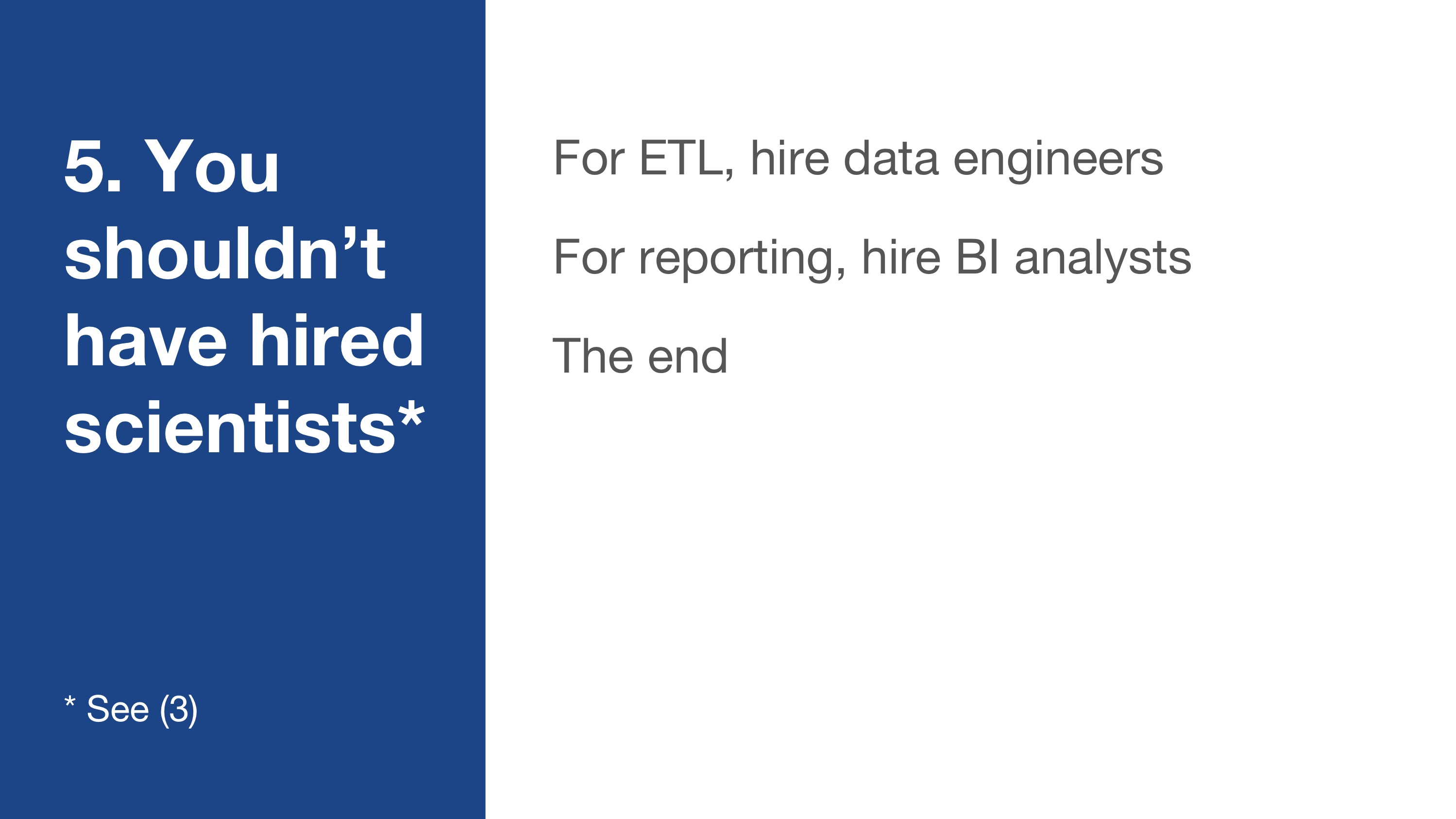

An applied science lab is a big commitment. Data can often be quite threatening to people who prefer to trust their instincts. R has a high risk of failure and unusually high levels of perseverance are table stakes. Do some soul searching - will your company really accept this culture?

Never let UX designers and product managers design a data product (even wireframes) using fake data. As soon as you apply real data it will be apparent that the wireframe is complete fantasy.

The real data will have weird outliers, or be boring. It will be too dynamic. It will be either too predictable or not predictable enough. Use live data from the beginning or your project will end in misery and self-hatred. Just like this poor leopard, weasel thing.

[1] See here for more.

Please get in touch with your own data disaster. Let’s get some data behind this and move Data Science forwards. All results will be fully anonymised. Use the form below or contact me via:

twitter: @martingoodson email: martingoodson@gmail.com