|

Today I’m going to talk about orbital mechanics, and specifically Lagrange points (and how much of the documentation on these points is incorrect!)

| |Today I’m going to talk about orbital mechanics, and specifically Lagrange points (and how much of the documentation on these points is incorrect!) Why do things orbit? How come they don’t just fall to the out of the sky? Why does the Moon orbit the Earth? Why do satellites orbit around us and not fall down? |

|The answer to these questions is that they are falling; they are continuously falling. They are falling around, and around the Earth. They have sufficient tangential speed that, instead of hitting the ground, the force of gravity constantly pulls them around in ‘circular’ paths (actually, it’s elliptical, but more of that later).|

|Today I’m going to talk about orbital mechanics, and specifically Lagrange points (and how much of the documentation on these points is incorrect!) Why do things orbit? How come they don’t just fall to the out of the sky? Why does the Moon orbit the Earth? Why do satellites orbit around us and not fall down? |

|The answer to these questions is that they are falling; they are continuously falling. They are falling around, and around the Earth. They have sufficient tangential speed that, instead of hitting the ground, the force of gravity constantly pulls them around in ‘circular’ paths (actually, it’s elliptical, but more of that later).| |

|

|

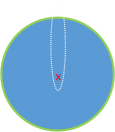

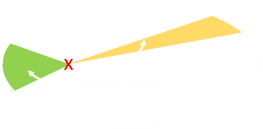

| |This subtly of this is one of Sir Isaac Newton’s great thought experiments. To the left is a copy of one of his original drawings.Imagine you are standing at the top of a tall cliff holding a cannon ball. If you drop the ball straight down, it’s going to accelerate straight down. However, if instead of dropping it, you fire it horizontally, it’s going to follow a curved path as it gets pulled down by gravity as it travels forward. If you launch it horizontally even faster it’s going to travel further, and the path it follows is called a parabola (well, strictly speaking it’s actually part of a very, very, eccentric ellipse, but more of that later).If you could fire the ball fast enough it would still fall, but the Earth is curving away from it, and it continuously falls. The question is not *“How high do you need to be to get into orbit?” but “How fast do you need to be going to get into orbit?”|

|This subtly of this is one of Sir Isaac Newton’s great thought experiments. To the left is a copy of one of his original drawings.Imagine you are standing at the top of a tall cliff holding a cannon ball. If you drop the ball straight down, it’s going to accelerate straight down. However, if instead of dropping it, you fire it horizontally, it’s going to follow a curved path as it gets pulled down by gravity as it travels forward. If you launch it horizontally even faster it’s going to travel further, and the path it follows is called a parabola (well, strictly speaking it’s actually part of a very, very, eccentric ellipse, but more of that later).If you could fire the ball fast enough it would still fall, but the Earth is curving away from it, and it continuously falls. The question is not *“How high do you need to be to get into orbit?” but “How fast do you need to be going to get into orbit?”|

Imagine you are standing at the top of a tall cliff holding a cannon ball. If you drop the ball straight down, it’s going to accelerate straight down. However, if instead of dropping it, you fire it horizontally, it’s going to follow a curved path as it gets pulled down by gravity as it travels forward. If you launch it horizontally even faster it’s going to travel further, and the path it follows is called a parabola (well, strictly speaking it’s actually part of a very, very, eccentric ellipse, but more of that later)*.

“How fast do you need to be going to get into orbit?”

|

And the answer is: Pretty Fast! To achieve a low Earth orbit you need to be travelling around 7,800 m/s. To escape the Earth you need to be travelling faster than approximately 11,000 m/s (around 25,000 mph, or Mach 33). The Earth curves away approximately 8 inches for every mile travelled. If you want to learn a little more about this check out the consequences of living on a sphere. |

The Earth curves away approximately 8 inches for every mile travelled. If you want to learn a little more about this check out the consequences of living on a sphere.

|Another interesting consequence is that, because you have to be going fast enough to get into orbit, if you start closer to the equator, and launch to the East, you get a leg-up from the rotation of the Earth. Launching close to the equator can give you boost of around 1,000 mph because of the spin of the Earth. If you look at a map of launch locations you can see they are banded closer to the equator, and not at the poles!It’s not just the leg-up in velocity that is a benefit. If your aim is to place a payload in Geosynchronous Orbit (which, by definition, are equitorial), then by launching from the equator you do not need to perform a plane change maneuver, saving valuable propellant (or allowing a more massive payload for the same rocket). This is so valuable the rockets are even launched from ship-born platforms floating near the equator.| |

|

It’s not just the leg-up in velocity that is a benefit. If your aim is to place a payload in Geosynchronous Orbit (which, by definition, are equitorial), then by launching from the equator you do not need to perform a plane change maneuver, saving valuable propellant (or allowing a more massive payload for the same rocket). This is so valuable the rockets are even launched from ship-born platforms floating near the equator.

*Elliptical Orbit and not a parabola?

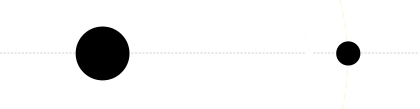

| |Strictly speaking, when you throw a ball into the air, you could technically say that the ball is in orbit.If you were to plot its path you’d get a very, very, eccentric ellipse with one of the foci at the center of the Earth (diagram not to scale). As mentioned earlier, with this foci being millions of meters away, the ellipse is essentially a parabola.When you throw a baseball, you’re launching it into an orbit; it’s just that it’s a pretty bad one and intersects with the ground! In the words of Douglas Adams, author of many fantastic books “Flying is simple. You just throw yourself at the ground and miss”|

|Strictly speaking, when you throw a ball into the air, you could technically say that the ball is in orbit.If you were to plot its path you’d get a very, very, eccentric ellipse with one of the foci at the center of the Earth (diagram not to scale). As mentioned earlier, with this foci being millions of meters away, the ellipse is essentially a parabola.When you throw a baseball, you’re launching it into an orbit; it’s just that it’s a pretty bad one and intersects with the ground! In the words of Douglas Adams, author of many fantastic books “Flying is simple. You just throw yourself at the ground and miss”| |

|

If you were to plot its path you’d get a very, very, eccentric ellipse with one of the foci at the center of the Earth (diagram not to scale). As mentioned earlier, with this foci being millions of meters away, the ellipse is essentially a parabola.

Up until the ball hits the ground, it doesn’t know that the ground is there. It’s attempting to orbit a point mass at the foci of that ellipse!

If we were able to replace the Earth with a point mass, a thrown ball would orbit and come back. Cool! (Next time someone makes fun of you for not throwing a ball far enough you can reply that, technically, it was in orbit for a little while!)

“Flying is simple. You just throw yourself at the ground and miss”

Keplers Laws

Where did the notion that orbits are ellipses come from? This idea was first proposed in the early 1600s by a mathematician called Johannes Kepler, and he proposed three laws of planetary motion which are named after him.

He formulated his laws based on the analysis of very accurate plantary observations taken by his mentor, astronomer, Tycho Brahe.

-

The Law of Ellipses - The path of the planets about the Sun is elliptical in shape, with the center of the Sun being located at one focus.

-

The Law of Equal Areas - An imaginary line drawn from the center of the Sun to the center of the planet will sweep out equal areas in equal intervals of time.

-

The Law of Harmonies - The ratio of the squares of the periods of any two planets is equal to the ratio of the cubes of their average distances from the Sun. (T2/R3 is constant).

|

The equal areas are a consequence of the conservation of energy and angular momentum.As the planet swings close to the sun, it speeds up (trading its gravitational potential energy for kinetic energy). As it travels further away, it slows down. |

As the planet swings close to the sun, it speeds up (trading its gravitational potential energy for kinetic energy). As it travels further away, it slows down.

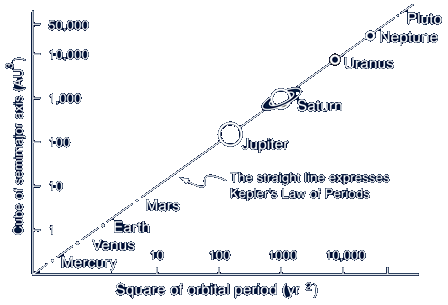

The graph below shows the Law of Harmonics for entities in our Solar System. By plotting T2 on one axis, and R3 on the other, the constant ratio can be seen as a straight line.

This ratio is agnostic of the mass of the planet. An object in orbit at the same orbital radius will have the same time period of rotation, irrespective of its mass. The further out the orbit, the slower the planet travels.

Let’s look at this with a simple interactive animation

Animation

Below is a sun showing what the orbits would be like for a planet in two different orbits. The red reference planet is fixed in orbit, but using the controls it’s possible to adjust the orbit of the green planet. Click the top right button to start/stop the animation. The ratio of the orbital radii can be adjusted using the triangular slider (or the buttons at the bottom). The other buttons just configure the display.

NOTE - The two planets are not interacting with each other. In this simulation it’s just a two body problem allowing you to compare how a single planet would orbit depending on it’s distance from the sun.

Did you notice that the only way to get the planets to rotate at the same rate is to have them on the same orbital radius? Hold onto that thought, we’ll come back to it later. The further away from the center of the sun the longer the time period of orbit. All orbits inside the red reference orbit have a time period less than it.

Newtons Law of Gravitation

| |Matter is attractive. Stuff is attracted to other stuff. Anything with mass experiences a force towards other mass. This force is called gravity. I would attempt to tell you what causes gravity, but the simple answer is that we just don’t know yet.We can measure the force, however, and there is a formula for it (shown left). The force of attraction between two lumps of mass is directly proportional to the each of their masses, and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between them.|

|Matter is attractive. Stuff is attracted to other stuff. Anything with mass experiences a force towards other mass. This force is called gravity. I would attempt to tell you what causes gravity, but the simple answer is that we just don’t know yet.We can measure the force, however, and there is a formula for it (shown left). The force of attraction between two lumps of mass is directly proportional to the each of their masses, and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between them.|

We can measure the force, however, and there is a formula for it (shown left). The force of attraction between two lumps of mass is directly proportional to the each of their masses, and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between them.

The G in the equation is a constant, named after Newton, and it’s value is approximately 6.674×10−11 N⋅m2/kg2

| |That’s a pretty small number and shows you that gravity is a very weak force (it’s by far the weakest of the four know fundamental forces: Gravitational, Electromagnetical, Weak Nuclear, and Strong Nuclear).The inverse square relationship means the pulling force rapidly diminishes with distance.|

|That’s a pretty small number and shows you that gravity is a very weak force (it’s by far the weakest of the four know fundamental forces: Gravitational, Electromagnetical, Weak Nuclear, and Strong Nuclear).The inverse square relationship means the pulling force rapidly diminishes with distance.|

The inverse square relationship means the pulling force rapidly diminishes with distance.

Two Body Problem

Because everything is pulling on everything else, determining what these interactions will do could gets infinitely complex. However, because the gravity force falls off with the square of the distance, the force of a body a long way away is typically dwarfed by those nearby. Mathematicians and Physicists use this principle to create simplified models. You will hear them talk about them talk about “The two body problem”, and the “Three body problem”. Here what they are doing is ignoring everything but the two or three massively dominant masses in a system (If you are trying to balance a playground see-saw, you are not worried if a fly lands on one side or another).

Earth-Moon

Let’s take a look at the Earth-Moon two body system. The Moon revolves around the Earth about once every month. It’s orbit is elliptical, but the average radius is about 239,000 miles (385,000 km).

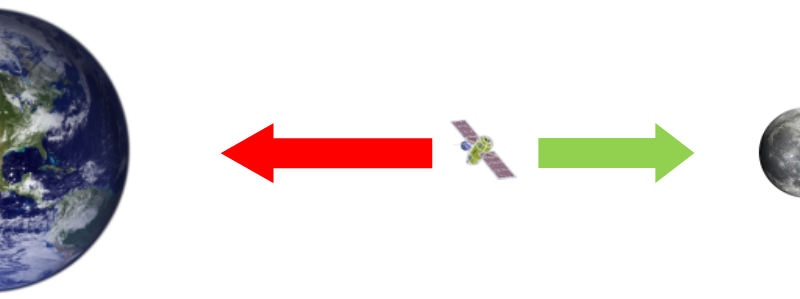

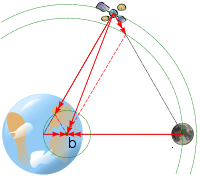

The Earth is approx 81 times more massive than the Moon. The force of gravity it imparts on other objects, relative to the Moon is similarly stronger. If we inserted a test mass (a third body), between these two entities it will experience forces from both of them. (Test mass, in this case, means something being so insignificant compared to the other two bodies that it’s effect on them is inconsequential). A satellite or spacecraft orbiting the Earth make less difference to orbit of the Moon than a fly landing on the deck of a massive cruise ship does to the trim of the boat.

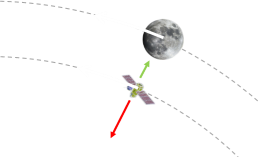

Above, not to scale, is a satellite in geocentric orbit (orbiting around the Earth) somewhere between the Earth and the Moon. It is being pulled towards the Earth by the gravity force from the Earth. It is being pulled towards the Moon by the mass of the Moon. Because the Earth is so much larger, it’s pull is larger, but because of inverse square, if the satellite moves further away from the Earth, this falls rapidly. Where does the pull from the Earth equal the pull from the Moon? Where these things are equal, we have something called a Gravity Neutral Point.

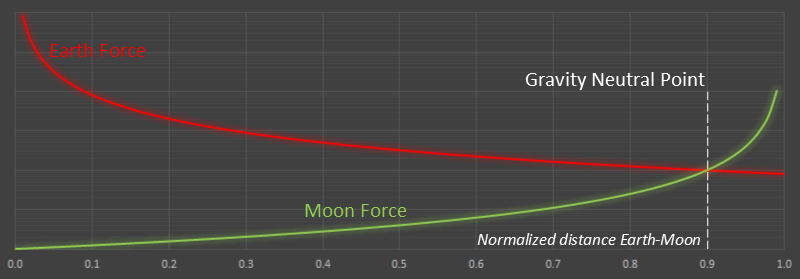

Above is a plot of the forces that would act on the satellite based on it’s position, normalized on the x-axis is the distance between the Earth and the Moon. The y-scale is logarithmic. Where the two curves intersect is the gravity neutral point. As you can see, because the Earth dominates, this is approximately 90% of the way to the Moon.

That’s pretty close to the Moon; approximately 24,000 miles (from the center of the Moon).

This point has special significance because, in theory, an object closer to the Moon than this distance will be pulled towards the Moon, and an object further away from the Moon than this point will be pulled back to Earth. It’s the crest of the hill. If you were travelling between the Moon and the Earth and passed this point, even with no propulsion, you’d be captured by the Moons gravity and be slowly pulled in. Or would you?

This point is erroneously called a Lagrange Point (more specifically L1, or Langrange point 1) by bad, bad physics text books and blogs. This is incorrect. Some books even go on to say that if you placed a penny at the neutral point it would stay there and not be pulled in either direction; this is also garbage! (for a couple of reasons).

The gravity neutral point is NOT a Lagrange Point.

Let’s help stop the internet propogating this mistruth. Let’s see what Lagrange Points really are …

Lagrange Points

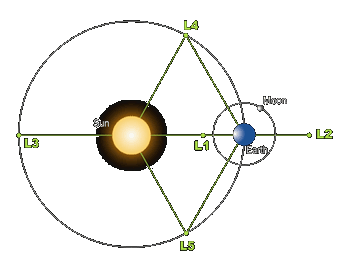

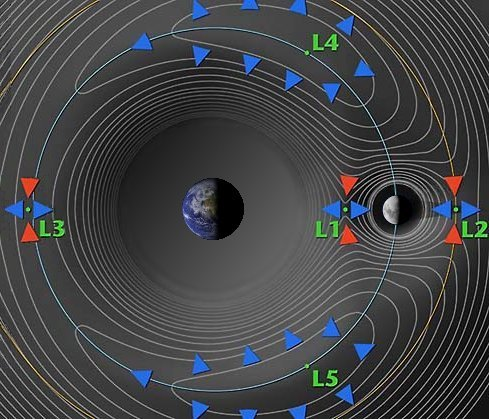

| |The problem with the situation described above is that is makes the unrealistic assumption that the objects are not moving. However, we know the Moon is orbiting around the Earth. Remember the animation earlier in the article? We determined that the only way a satellite can orbit with the same period as another is if they were the same distance away from the center. A penny left a this ‘gravity neutral point’ is closer to the Earth than the Moon, consequently it will be orbting inside (and faster) than the Moon, and zip away.Now, there is a point between the Earth and the Moon where a penny (or satellite) can orbit at the same rate at the Moon (and thus stay lock stepped with it), and it is this what we call a Lagrange Point.|

|The problem with the situation described above is that is makes the unrealistic assumption that the objects are not moving. However, we know the Moon is orbiting around the Earth. Remember the animation earlier in the article? We determined that the only way a satellite can orbit with the same period as another is if they were the same distance away from the center. A penny left a this ‘gravity neutral point’ is closer to the Earth than the Moon, consequently it will be orbting inside (and faster) than the Moon, and zip away.Now, there is a point between the Earth and the Moon where a penny (or satellite) can orbit at the same rate at the Moon (and thus stay lock stepped with it), and it is this what we call a Lagrange Point.|

Now, there is a point between the Earth and the Moon where a penny (or satellite) can orbit at the same rate at the Moon (and thus stay lock stepped with it), and it is this what we call a Lagrange Point.

|There is a point, inbetween the Earth and the Moon, where, even though it’s at a smaller radius (and so wants to orbit faster), an object placed there is pulled by the Moon’s gravity with just the correct force to counteract the difference between the angular accelerations, reducing the resultant force on the satellite and making it orbit with the same time period as the Moon.This point, between the two large bodies, is called L1, or Langrange Point 1 (sometimes a Libration point). We’ll see how to calculate this distance later, but the L1 is significnatly closer to the Earth than the gravity neutral point (The L1 point is approx 84% of the way to the Moon c.f. the 90% calculated for the neutral point). Passing the L1 point marks the place where the satellite stops orbiting the Earth and starts orbiting the Moon.| |

|

This point, between the two large bodies, is called L1, or Langrange Point 1 (sometimes a Libration point). We’ll see how to calculate this distance later, but the L1 is significnatly closer to the Earth than the gravity neutral point (The L1 point is approx 84% of the way to the Moon c.f. the 90% calculated for the neutral point). Passing the L1 point marks the place where the satellite stops orbiting the Earth and starts orbiting the Moon.

But L1 is not the only point where a satellite can orbit at the same period as the Moon. There’s more …

On the other side of the Moon, is an orbit that normally would have a longer time period than the Moon, but the combined sum of the gravity of the Moon and the Earth pull the satellite in stronger and cause it to orbit with the same time period as the Moon. This point is called L2.

We’re not finished yet, there’s more …

There’s also a point, on the other side of the Earth, pretty much directly opposite the Moon, where the force from the Earth, plus the very weak force from the Moon combine to put a satellite there in an orbit the same time period as the Moon. This point is called L3. (The radius of this orbit is ever so slightly larger than that of the Moon, because the force acting on it is the combined pull from both the Earth and the Moon).

Math

The location of L1 is the solution to the following equation, balancing gravitation and the centripetal force:

Here r is the distance from the L1 point to the Moon, R is the distance between the Moon and the Earth, and Me and Mm are the masses of the Earth and Moon, respectively.

Rearranging this for r results in a quintic equation that needs solving, but if we apply the knowledge that Me » Mm, then this greatly simplifies to this approximation:

Simarly, for L2, the solution can be calculated from balancing the gravitational and centripetal force on the other side of the Moon:

Applying the same simplification as above results in the same answer. With this approximation, the L2 point is the same distance from the rear of the Moon as the L1 point is infront.

Finally the location for L3 is the solution to this equation (though here, r is the distance that L3 is from the Earth, not the Moon).

Again, applying the simplification allows this approximation to be determined:

L1, L2, and L3

L1, L2, and L3 all lie in a straight line through the center of both the Earth and Moon. The concept of these three points was discovered by Leonard Euler.

However, a couple of years later Italian mathematician Giuseppe Ludovico De la Grange Tournier realised there were actually five points, so they are named after him as Lagrange Points.

So where are the other two points?

L4 and L5

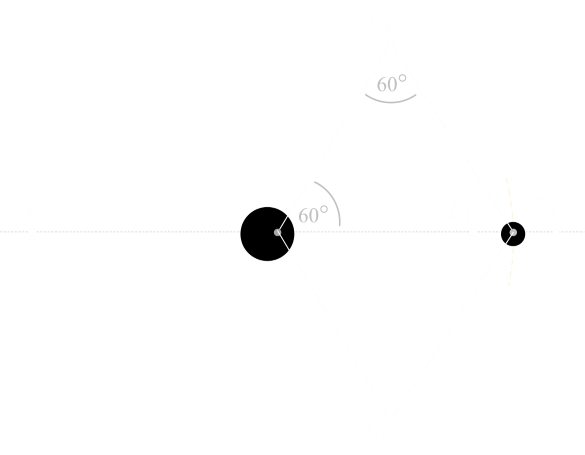

L4 and L5 are symmetrically placed either side of the center line and at positions 60° from it at th vertices of equilateral triangles (with the other vertices being the center of the center of the Moon and the barycenter of the Earth-Moon system).

|

The barycenter is the common center of mass of the Earth-Moon pair, and it is around this point that the two revolve, like a bolas. However, since the Earth is considerably more massive than the Moon, the barycenter is still located inside the Earth (it’s about 1,700 km below the surface). If the Moon and Earth were nearer the same mass, the barycenter about which they’d spin would be outside both of them, and the would spin around it like a giant dumbell.As it happens, in the Earth-Moon system, it’s more like the wobble of an Olympic hammer thrower as they spin up. |

As it happens, in the Earth-Moon system, it’s more like the wobble of an Olympic hammer thrower as they spin up.

|The L4 and L5 points lay on an orbit just outside the orbit of the Moon, and the vector mathematics balances out such that the pull from the Moon along that line is equal to the component from the Earth. This vector triangle can be seen in this diagram frim Wikipedia.L4 is traditionally defined as the point leading the orbit, and L5 lagging.| |

|

L4 is traditionally defined as the point leading the orbit, and L5 lagging.

Hill Spheres

| |In the above examples, I used Earth-Moon system to demonstrate Lagrange points, but I could have just as easily used the Sun-Earth system. In this case, the Sun is the center, and the Earth revolves around this. There are corresponding L1-5 points for the Sun-Earth system. Because the Sun is so massive, the L1 point for the Sun-Earth system is just 1.5 million km from the Earth.When dealing with these things, it’s helpful to be able to ignore other bodies that have negligable impact on the system.An astronomical body’s Hill Sphere is the region that, inside of which, that body’s gravitational pull dominates the actions of something inside in. The boundary of a Hill Sphere is a zero velocity surface. Anything inside the Moon’s Hill Sphere will tend to become a satellite of the Moon instead of the Earth. The Earth itself has a Hill Sphere, and outside of this sphere, an object passing through will be more dominated by the Sun and if it does not have sufficient energy to pass through, will become a satellite of the Sun instead of the Earth.|

|In the above examples, I used Earth-Moon system to demonstrate Lagrange points, but I could have just as easily used the Sun-Earth system. In this case, the Sun is the center, and the Earth revolves around this. There are corresponding L1-5 points for the Sun-Earth system. Because the Sun is so massive, the L1 point for the Sun-Earth system is just 1.5 million km from the Earth.When dealing with these things, it’s helpful to be able to ignore other bodies that have negligable impact on the system.An astronomical body’s Hill Sphere is the region that, inside of which, that body’s gravitational pull dominates the actions of something inside in. The boundary of a Hill Sphere is a zero velocity surface. Anything inside the Moon’s Hill Sphere will tend to become a satellite of the Moon instead of the Earth. The Earth itself has a Hill Sphere, and outside of this sphere, an object passing through will be more dominated by the Sun and if it does not have sufficient energy to pass through, will become a satellite of the Sun instead of the Earth.|

When dealing with these things, it’s helpful to be able to ignore other bodies that have negligable impact on the system.

As you can guess from our discussion, the L1 and L2 points lie on the edge of an entity’s Hill Sphere. If a is the average orbital radius then the Hill Sphere size between a large body of mass M, and a smaller body with mass m, looks the same as the formula for the L1 distance.

An object passing into the Hill Sphere of the Moon, if it does not have sufficient energy to come out again, will become a satellite of the Moon.

Because we know the L1 point for the Sun-Earth system is 1.5 million km, we know that a satellite cannot orbit the Earth further out than that (if it did, it would get more attracted to the Sun and head off in that direction). This means that it’s not possible for the Earth to have a satellite orbiting with a time period of greater than approximately seven months (the corresponding time period for an orbit of that radius).

(Also as the Moon is very clearly inside the Sun-Earth Hill Sphere, it has no interest in flying off and orbiting the Sun instead of us, and that’s a good thing).

Everything has a Hill Sphere

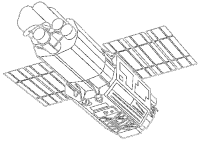

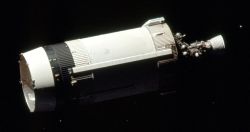

| |Every object has a Hill Sphere. A spaceman in his suit has a Hill Sphere, an asteroid does, a space station does. Like Matryoshka dolls, it’s possible for a space station to have little baby satellites in orbit around it! It does, however, depend on the other dominant masses in the region. For example, when the Space Shuttle was in low earth orbit, it had a Hill Sphere radius of about 120 cm (its mass was about 100 tonnes); since this radius is smaller than the shuttle istelf it’s sphere is inside its structure, so it’s not going to pick up orbiting debris and have it’s own satellites! Now if we had a shrink ray, and could shrink the shuttle down to a point mass, that would be different! (Or pilot the shuttle into inter-stellar space!)|

|Every object has a Hill Sphere. A spaceman in his suit has a Hill Sphere, an asteroid does, a space station does. Like Matryoshka dolls, it’s possible for a space station to have little baby satellites in orbit around it! It does, however, depend on the other dominant masses in the region. For example, when the Space Shuttle was in low earth orbit, it had a Hill Sphere radius of about 120 cm (its mass was about 100 tonnes); since this radius is smaller than the shuttle istelf it’s sphere is inside its structure, so it’s not going to pick up orbiting debris and have it’s own satellites! Now if we had a shrink ray, and could shrink the shuttle down to a point mass, that would be different! (Or pilot the shuttle into inter-stellar space!)|

In low Earth orbit, anything with a density less than that of solid lead is going to have a Hill Sphere inside of itself (and thus passing objects will be more interested in the Earth than it).

As we move further away from the Earth, the influence of Earth’s gravity reduces. A geostationary satellite only needs to be more than 6% of the density of water to support satellites of its own.

| |If someone were crazy enough to launch a sphere of gold into low earth orbit it would be possible to orbit grains of rice around it.|

|If someone were crazy enough to launch a sphere of gold into low earth orbit it would be possible to orbit grains of rice around it.|

Celestial Mechanics

| |Because L1 points lie on zero velocity boundaries of Hill Spheres they are the celestial cross roads between different orbits. A spaceship sitting at L1 can nudge itself in one direction and go inside the Hill Sphere of that object, or nudge itself in another direction and go in the direction of the other sphere.|

|Because L1 points lie on zero velocity boundaries of Hill Spheres they are the celestial cross roads between different orbits. A spaceship sitting at L1 can nudge itself in one direction and go inside the Hill Sphere of that object, or nudge itself in another direction and go in the direction of the other sphere.|

For example, if you want to launch a satellite and put it into orbit around the Sun, you can launch from the Earth and move to the Sun-Earth L1 transfer point, then give it a gentle kick in the right direction and it will change from a geocentric orbit (around the Earth), and into a heliocentric orbit (around the Sun).

A fascinating consequence of this is that something coming the other way can also pass through these gateways. As we’ll see later, the L1 points are unstable (with respect to the energy curve), so can be chaotic. Small differences in velocities (caused by other bodies in the region) can cause things to dosy-doe and flip between the spheres on either side of the zero velocity boundary.

| |No discussion about this is complete without mentioning J002E3, a piece of space junk identified by amateur astronomer Bill Yeung in 2002. Initially thought to be an asteroid, it has since been identified as the S-IVB third stage of the Apollo 12 Saturn V rocket, launched in 1969.After jettison, it’s believed to have gone into a high geocentric orbit for a couple of years, then passed close to the Sun-Earth L1 point and jumped ship to transfer into a heliocentric orbit and spent a few decades on a sojourn orbiting around the Sun, before returning in 2002.|

|No discussion about this is complete without mentioning J002E3, a piece of space junk identified by amateur astronomer Bill Yeung in 2002. Initially thought to be an asteroid, it has since been identified as the S-IVB third stage of the Apollo 12 Saturn V rocket, launched in 1969.After jettison, it’s believed to have gone into a high geocentric orbit for a couple of years, then passed close to the Sun-Earth L1 point and jumped ship to transfer into a heliocentric orbit and spent a few decades on a sojourn orbiting around the Sun, before returning in 2002.|

After jettison, it’s believed to have gone into a high geocentric orbit for a couple of years, then passed close to the Sun-Earth L1 point and jumped ship to transfer into a heliocentric orbit and spent a few decades on a sojourn orbiting around the Sun, before returning in 2002.

It hung around again for a few Earth orbits, then left again back through the L1 point to orbit the Sun again. NASA predicts it will visit us again in 2040. Below is a fascinating animation/simulation they made of its last visit.

I don’t know about you, but I smiled the entire day when I first heard about this. If you watch the animation you can see how the Moon perturbed the Apollo stage and sent it back towards the L1 point and off back into an orbit around the Sun. See you again in a few million miles J002E3.

Stability

The five Lagrange points rotate with the system as it revolves.

To the left is an animation also showing the gravity potentials around these locations.

Lagrange points L1, L2, and L3 are unstable. Objects placed there will drift, and the more they drift, the stronger the forces will be to move them further away. Satellites placed in these locations need assistance to remain on station.

L4 and L5 are stable locations (with the caveat that the ratio of masses of the other two bodies is such that the center mass needs to be at least 24.96x that of the smaller body)*, and objects placed there will tend to remain there. These regions of stability are slightly ‘kidney’ shaped.

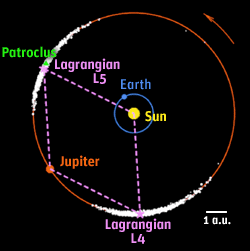

|Because of this stability, space dust, junk and asteroids tend to collect in L4 and L5 points in orbits (they are also great locations to base colonies if you are writing science fiction books). Astronomers have even given these locations names. Asteroids resting in L4 locations are called “Greeks”, and those in L5 are called “Trojans” (from camps in the Iliad). To the right is a plot of the potentials.Here’s a plot showing a some of the asteroids that Jupiter has managed to capture in it’s Langrange points. |

|

|

|

Here’s a plot showing a some of the asteroids that Jupiter has managed to capture in it’s Langrange points.

L4 and L5 are like celestial parking spaces.

Points L4 and L5, act like kidney shaped indentations or bowls, and if you carefully roll balls into them, the balls stay inside, riding up and down the sides if perturbed slightly. Points L1, L2, and L3 are like trying to place balls onto hill tops; without constant attention, they will roll off and down the hill in one direction after the slightest nudge.

Man Made Satellites at Lagrange Points

There are lots of great reasons to place satellites in Lagrange Points (even if they require gentle on station adjustments). A satellite at Earth-Moon L2 would allow for communication with the far side of the Moon. A satellite at the Sun-Earth L1 would allow constant observation of the Sun and the Earth; there are already climate observing satellites there. The proposed James Webb Space Telescope (the successor to the Hubble), will sit at the Sun-Earth L2 to reduce light noise.

It’s been suggested that Earth-Moon L4 and L5 might make good locations for man-made space colonies, but unfortunately these regions live outside the protection of the Earth’s magnetosphere and so get bombarded with cosmic rays.

Science Fiction

| |Science Fiction authors (and some UFO conspiracy people) like to talk about the concept of a Dark Twin Earth, or a mysterious Planet X that orbits around the Sun (in what would be Sun-Earth L3 point). They argue that, because it is always 180° behind us, it is always behind the Sun, and that is the reason we’ve never seen it.|

|Science Fiction authors (and some UFO conspiracy people) like to talk about the concept of a Dark Twin Earth, or a mysterious Planet X that orbits around the Sun (in what would be Sun-Earth L3 point). They argue that, because it is always 180° behind us, it is always behind the Sun, and that is the reason we’ve never seen it.|

This is bogus for a couple of reasons. The first is that we’ve actually sent things over to the L3, and they’ve not seen anything. But more fundementally, L3 is unstable, so it’s impossible for a planet there to remain hidden. Even if it started out with the same orbital period and directly behind the Sun, it would not stay there. It would eventually drift out from behind the Sun. It can’t hide forever.

You can’t argue with science!

You can find a complete list of all the articles here. Click here to receive email alerts on new articles.

Click here to receive email alerts on new articles.