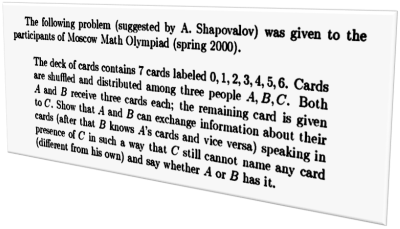

The 2016 Olympic Games are currently happening in Rio. Let’s take a look at a puzzle from another Olympiad: The Moscow Math Olympiad. This is a puzzle that featured in the Spring Olympiad in 2000. The puzzle recently came to my attention because, at the time, there was a little controversy in what kind of answers were acceptable solutions.

The Puzzle

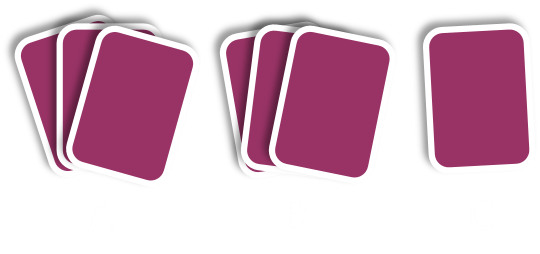

There are seven cards, numbered sequentially 1 – 7 (in the original puzzle they were numbered 0 – 6, but that does not matter). These cards are thoroughly shuffled then dealt out between three people: A, B and C.

Player A gets three cards. Player B also gets three cards. Player C receives a single card.

|

The challenge begins: Player A looks at his cards and makes a statement that he knows to be true. His statement is heard by all the players.Next player B looks at his cards and makes a statement that he also knows to be true. This is again heard by all the players. |

Next player B looks at his cards and makes a statement that he also knows to be true. This is again heard by all the players.

|After these two statements are heard, player A now knows what cards player B is holding (and therefore, also, what card player C is holding). Similarly, player B also knows all the cards that player A is holding, and what card player C is holding. However, player C, even though he heard all the same statements does not know the location of any card other than his own (specifically, if you asked player C who was holding any card other than the card he had, he could not be able to say).| |

|

|

| |This is the puzzle: What can A and B publicly say that will communicate the contents of their hands so that they each know the make-up of the other’s hand without disclosing information to C?No collusion is allowed. Player A and Player B are not allowed to meet beforehand and conspire to create a secret code, language, or indication system.|

|This is the puzzle: What can A and B publicly say that will communicate the contents of their hands so that they each know the make-up of the other’s hand without disclosing information to C?No collusion is allowed. Player A and Player B are not allowed to meet beforehand and conspire to create a secret code, language, or indication system.|

No collusion is allowed. Player A and Player B are not allowed to meet beforehand and conspire to create a secret code, language, or indication system.

|There is a way for players A and B to make statements about their hands that can be used/interpreted by the other person without requiring a pre-arranged system (meaning there is no secret knowledge component; Everything that A and B knows, you can assume that C also knows). Can you work it out?| |

|

Think about it

|It’s worth thinking about this for a few minutes to see if you can come up with a solution. I’ll wait here if you want to pause and come back.There are two components to this puzzle: The first is to come up with a mechanism that allows player A and player B to communicate sufficient information to the other player. The second component is a proof that this does not leach information to player C.| |

|

There are two components to this puzzle: The first is to come up with a mechanism that allows player A and player B to communicate sufficient information to the other player. The second component is a proof that this does not leach information to player C.

Controversial Solution

There’s a clever mathematical solution (which we’ll explore below), and this is what the organizers were intending the participants to come up with. However, many of the entries came back with a simpler solution along these lines:

Without loss of generality, assume player A has cards {1,2,3} and player B has cards {4,5,6}. Player A looks at his cards and says to Player B:

Player A: “Either I have the cards numbered 1,2,3 or you do.”

Player B then looks at his cards and says to Player A:

Player B: “Either I have the cards numbered 4,5,6 or you do.”

Both of these statements are true (after all player C has the 7), but they are conditional. From a purely logical perspective, player C does not know which player has {1,2,3} and which has {4,5,6} (So if asked “who has 5?” they would not be able to answer). It gets down to semantics in the question wording and the difference between “true statements” and “statements known to be true”. (The only way for A to know his statement to be true is if he actually is holding {1,2,3} which will tell C that he is).

| |In the end, the judges of the competition ruled that the wording of the question was sufficiently vague and so gave full marks for those that answersed the question in this way.|

|In the end, the judges of the competition ruled that the wording of the question was sufficiently vague and so gave full marks for those that answersed the question in this way.|

Need convicing on the subtle difference?

Not convinced there is a difference? Take this thought experiment. Imagine now that there are only three cards, and everyone gets one card each (again without loss of generality):

|- Player A gets card 1.- Player B gets card 2.- Player C gets card 3.| |

|

Before any statements are made, then player C does not know who has card 1, and who has card 2. (But he knowns he has 3).

Now, if the same strategy as described above is applied the following statements will be heard:

Player A looks at his card and says to Player B:

Player A: “Either I have the 1, or you do.”

Player B looks at his card and says to Player A:

Player A: “Either I have the 2, or you do.”

Now let’s see what Player C can deduce from this. From purely logical “One of us has card 1.” and “One of us has card 2.” statements, there is no information to be gained. However, distilling the information (however it is encoded) that can be transmitted by Player A, there are four possible messages that Player A can convey:

-

My card is 1.

-

My card is 1 or 2.

-

My card is 1 or 3.

-

My card is 1, 2, or 3.

Now #1 breaks the rules, as it will convey directly to player C information. #4 is redundant as it conveys no information to anyone. Player A, however, does not know if #2 or #3 is the correct message to say (as he does not know what card is the held by player B), so could not make either of those statements. Therefore if he made the statement “One of us has card 1”, then the only way he could have made that statement is if he knew he was holding that card.

Mathematical Solution

| |This is the solution the organizers of the event were anticipating.The keys to this solution lie in modulo arithmetic and cakes (OK, I made the second part up).But seriously, as there are seven cards, we know the total of all the cards together.If we added up all the cards, we’re get 1 + 2 + 3 + 4 + 5 + 6 +7 = 28|

|This is the solution the organizers of the event were anticipating.The keys to this solution lie in modulo arithmetic and cakes (OK, I made the second part up).But seriously, as there are seven cards, we know the total of all the cards together.If we added up all the cards, we’re get 1 + 2 + 3 + 4 + 5 + 6 +7 = 28|

The keys to this solution lie in modulo arithmetic and cakes (OK, I made the second part up).

If we added up all the cards, we’re get 1 + 2 + 3 + 4 + 5 + 6 +7 = 28

Now, imagine 28 is represented by the entire cake. We can carve the cake into three pieces (with sizes proportional to the totals of each of the players cards). If we know any two of the three cake slice sizes, we can determine the third. If player A can communicate information about his sum, and player B can do the same, then each can determine the size of the missing slice (player C’s number). By knowing the size of the missing slice (what player C is holding), and combining it with their own information, both player A and player B can deduce what each other is holding.

The trick lies in A and B being able to communicate information about their slice size without giving it away totally.

They can’t simply say “My total is N”, because this might give information to player C. Yes, some totals are ambiguous, such as “My total is 12” {7,3,2} or {5,4,3} … and this does not leach information, but if player A said “My total is 6”, then there is only one way this could be possible {1,2,3}, so C would then have all the information needed to know everyone else’s number.

If you’ve read my article on Sharing Secrets and Distributing Passwords, and collusion was allowed, a possibile solution would be for A and B to agree on a random number beforehand (for instance 21). Player A could then sum his cards and add this to the secret number and broadcast the total. Player C would not know how much of this total was from the cards, and how much was the secret numbers. Player B would know what to subtract to get the raw total. A nice solution, but we said no prior collusion or secret knowledge is required to solve this puzzle.

The solution is for both player A and player B to declare the sum of their cards modulo 7 (the remainder when the sum is divided by 7).

First of all, player A will declare his total mod 7. Player B can do the same calculation on his collection. Because he knows that the total sum of all the cards mod 7 is zero (28 mod 7=0), he knows what card is being held by C.

Ex. If A has {1,4,5} and B has {2,3,7}

Because 28 mod 7 = 0 then the card being held by C is what will make the modulus sum zero.

It’s a little bit like know that the total of three items purchased in a store is a round number of pennies (ends in a zero). If you know the end digit of two of the prices, you can calculate the third.

Proving no leaching of information

Mathematically, we’ve shown that this solution will work; all that what we need to prove/show now is that by stating the modulus sum we are not leaching any information to C by giving information that can only happen with one distinct set of numbers.

We can show this be enumerating out all the possible sets. When player A or B makes the statement “The total of my cards mod 7 is 3”, an equivlant to what this is saying is:

“My cards are one of the following sets:

(All of the above sets have a sum mod 7 of 3).

If you look closely, there is no card number that only appears in one set. Every number appears in at least two sets. Therefore, even if player C knows the modulus 7 sum is three, there is no way for him to learn any individual card number. (Put another way, even though C knows his number and can remove all the sets that contain his number, there are still multiple sets that the answer can be).

Here are all the sets for each possible modulus answer:

| MOD 7 | Sets | —— |

| 0 | {1,2,4} {1,6,7} {2,5,7} {3,4,7} {3,5,6} | |

| 1 | {1,2,5} {1,3,4} {2,6,7} {3,5,7} {4,5,6} | |

| 2 | {1,2,6} {1,3,5} {2,3,4} {3,6,7} {4,5,7} | |

| 3 | {1,2,7} {1,3,6} {1,4,5} {2,3,5} {4,6,7} | |

| 4 | {1,3,7} {1,4,6} {2,3,6} {2,4,5} {5,6,7} | |

| 5 | {1,4,7} {1,5,6} {2,3,7} {2,4,6} {3,4,5} | |

| 6 | {1,2,3} {1,5,7} {2,4,7} {2,5,6} {3,4,6} |

Completing the loop from the example above where Player A announced 3 and Player B announced 5. What information does Player C know? He knows that he is holding the 6, so looking at the two relevant rows above, and removing those sets that contain a 6.

| MOD 7 | Sets | —— |

| 3 | {1,2,7} {1,3,6} {1,4,5} {2,3,5} {4,6,7} | |

| 5 | {1,4,7} {1,5,6} {2,3,7} {2,4,6} {3,4,5} |

There is no number that is common and present in all the sets on either of the rows. Player C has no way to know where any individual number, other than his own, is located. Circular shifting does not produce any different results.

Alternative statements from B

|After player A makes his statement, player B has sufficient information to know the location of every card. Therefore he doesn’t have to state his modulus sum, instead, he can just as easily declare “Player C is holding card N”. This does not give any information to C that C does not already know, and is all that is required by A to know the cards that B is holding. It also makes him look pretty cool.| |

|

More

| |If this all sounds like sorcery, or if you want to learn a little more about practical applications of this principle, read my article about Hamming Codes and how this theory is used provide error correction circuitry for computer memory chips.If you found this puzzle very easy, try your teeth on this one The Impossible Escape which uses similar principles.|

|If this all sounds like sorcery, or if you want to learn a little more about practical applications of this principle, read my article about Hamming Codes and how this theory is used provide error correction circuitry for computer memory chips.If you found this puzzle very easy, try your teeth on this one The Impossible Escape which uses similar principles.|

If you found this puzzle very easy, try your teeth on this one The Impossible Escape which uses similar principles.

You can find a complete list of all the articles here. Click here to receive email alerts on new articles.

Click here to receive email alerts on new articles.