· Read in 10 minutes · 2080 words · All posts in series ·

My memory, like yours, exerts a powerful influence over my interaction with the world. It is reconstructive and evocative; I can easily form an image of hot December days in the South African summer, and remember my first time—it was morning on an Easter Sunday in April a few years ago—that I saw and felt snow. My memory is so powerful that, using the words of Endel Tulving, it allows me to ‘violate the law of irreversibility of time’; to ‘bend times arrow in a loop’; to become a mental time traveller! This super-power opens up new strategies for learning in brains and machines: we can re-live our former selves; re-interpret and consolidate experiences from our past to better understand the the world of the present; and crucially, make rapid decisions about our behaviours for the future.

Time travellers need time machines. And ours works by continually storing the episodes of our lives: our ongoing perceptions and actions, and the context surrounding them. This helps us form an autobiographical memory—a memory of the self—or more simply, an episodic memory. It is this type of memory that supports the rapid learning that humans effortlessly achieve. In contrast, the associative learning systems we previously examined used a very different type of memory, a long-term memory that was gradually formed by repeated exposure to rewarding experiences. There are evidently different interacting memory systems at play, and this post explores the neuroscience and machine learning of such complementary learning systems.

Time machines aren’t easy to build; they also aren’t easy to use. But our brains seem able to form and use autobiographical memories that allow for easy recollection of the past, and can infer complex dependencies between our past actions and their eventual outcomes. Using the framework of Marr’s levels of analysis, this leads us to the computational question: how does the brain store unique experiences and make them available for rapid learning and adjustment of behaviours?

We gain important clues by going back in time, to 1957, to the now famous surgical case of a Henry Molaison (patient HM). Henry suffered from epilepsy, whose source was localised to damage to his left and right medial temporal lobes (MTL). As treatment, he underwent a resection of this area of his brain. But Henry, now cured of his epilepsy, experienced a severe side-effect: from then onwards he was unable to remember the ongoing experiences of his life (anterograde amnesia). The same is true for Kent Cochrane (patient KC), and many other similar patients. The damage to the MTL and the hippocampus common in these patients, and what is subsequently an inability to form and use episodic memory, is the first hint as to the importance of this brain region.

The medial temporal lobes (MTL) lie on the inner (medial) side of the temporal lobes. The MTL comprises three regions: the hippocampal formation, the perirhinal cortex and parahippocampal cortex. The hippocampal formation is itself comprised of the hippocampus, the entorhinal cortex and the subicular complex. And again, the hippocampus is comprised of the hippocampus proper, consisting of four CA (Cornu Ammonis) areas CA1-CA4, and the dentate gyrus. Using the entorhinal cortex, the hippocampus is connected to other parts of the brain.

We obtain a large body of evidence explaining the function of these brain regions by comparative studies of lesioned and healthy brains using positron emission tomography (PET) and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). In these neuro-imaging studies, patients participate in tasks requiring navigation in virtual environments, imagining fictitious experiences, and word-cue tasks, which quickly establish the hippocampus as being critical to episodic memory [1][2][3]. Single cell recordings in rats suggest that abstract representations are stored rather than any direct sensory perceptions: Leutgeb et al. (2007) [4] find that hippocampal codes—formed in the dentate gyrus through pattern separation and eventually stored in the CA3 region—represent diverse sets of stimuli, from faces to objects, with consistent firing across different forms of the stimuli. Sparsity is a also a property of the hippocampus [5]. And ultimately, our memory systems are interactive and complementary. Early phases of learning rely on the medial temporal lobe and episodic memory for rapid decision-making, but shifts with training and experience to the use of dopaminergic neurons in the midbrain and associative learning for more sustained behaviour [6][7].

This leads us to what we can call the episodic learning hypothesis: the brain stores new experiences using an episodic memory system, and by allowing for inspection and recall, uses this system to learn about its environment and for decision making. Our investigation has shown that episodic learning systems also interact with other systems, leading us to the more general theory of complementary learning systems, which highlights the important role of the neocortex for gradual acquisition of knowledge and the hippocampus for rapid learning of individual experiences. Important papers in this area of neuroscience are:

The need for rapid learning has led us to the computational question of how the brain makes possible mental time travel and rapid learning. An algorithmic solution is based on the use of episodic memory that stores individual experiences and their contexts, allowing us to interrogate our memory of the past, and to inform our future actions using this knowledge. This is supported by an implementation in brains through the use of a hippocampus that uses sparse codes and pattern separation to store abstract representations of our perceptions, and a reliance on the medial temporal lobe during early learning.

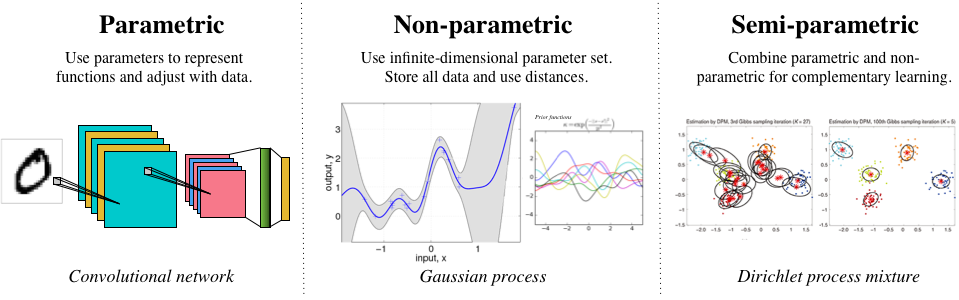

In machines, the distinction between fast and slow learning is based on the type of statistical model that is used. One view aligning brains and machines is of parametric models paralleling the memory systems of the neocortex,* non-parametric* models paralleling the episodic systems of the hippocampus, and semi-parametric models as a structure for complementary learning. Machine learning models are much more fluid than such a taxonomy would suggest, but this distinction is useful for building conceptual understanding.

One general aim of machine learning is to discover functions hidden in data. Different types of models can be used to achieve this.

k-Neighbourhood for a test data point.

The simplest non-parametric approaches think of the data points as model parameters. The model uses an explicit memory to store all the data features x, and if available, labels or other side-information y, and defines a similarity or distance between any two data points using a function d(x’,x). The most famous example is the k-nearest neighbour (kNN) method for making a prediction of a function value at a test point  . Its steps are simple: 1) Compute the distance between

. Its steps are simple: 1) Compute the distance between  and every point in the data

and every point in the data  in memory, and sort them according to distance. 2) The top k data points closest to

in memory, and sort them according to distance. 2) The top k data points closest to  defines the k-neighbourhood

defines the k-neighbourhood  , and the kth entry is the kth order statistic

, and the kth entry is the kth order statistic  . 3) For regression we form a prediction by averaging over the values y in the k-neigbourhood; for classification we do majority voting.

. 3) For regression we form a prediction by averaging over the values y in the k-neigbourhood; for classification we do majority voting.

For kNNs, every data point in the neighbourhood is treated the same, i.e. uniformly. We can generalise this to non-uniform treatments, and is how kernels, one of the most popular nonparametric tools, can be introduced. In the non-parametric-episodic framework, data points are stored in memory and decisions are made based on similarity using a kernel [8]. Non-parametric methods are in widespread use for decision making and action selection in machines, including:

A simple taxonomy of statistical models.

Semi-parametric models combine nonparametric and parametric models. As Nils Hjorts says, they can ‘build non-parametric uncertainty around given parametric models’ [9][10]. Partially parametric models are one common example that explain part of a prediction using a parametric component and another part using a non-parametric component. Consider observed data that appears as two feature sets x and z, that together correspond to a target y. A partially parametric model explains the data x using a parametric model f (e.g., a linear function) with parameters  , and the data z using a nonparametric model g:

, and the data z using a nonparametric model g:

A Gaussian process with a parameterised mean function (e.g., a linear function or deep network) can also be used to implement this semi-parametric model. A different type of semi-parametric approach would build a gaussian process whose kernel function is defined using transformed data  , where

, where  can again be any parameterised function.

can again be any parameterised function.

And don’t forget mixture models. We can build finite mixtures of non-parametric methods: when the mixture is additive, we get mixtures of non-parametric experts-type models, when the mixture is geometric we get Bayesian committee machines. In reverse, we can form non-parametric mixtures of parametric models. Using the Dirichlet process as the non-parametric distribution, we can form Dirichlet process mixture models. Expository papers in this area are:

Episodic systems in the brain are paralleled by non-parametric approaches in machines. And similarly, complementary learning approach based on the interaction between episodic and associative learning systems is paralleled by semi-parametric approaches. Importantly, this combination leads us to an important principle of complementarity that allows for rapid learning and acting, and efficient use of experiences. We have explored key principles of intelligent systems: prediction, sparsity, modularity, and now, complementarity. When combined, they give us a complex and dazzling view of the marvel that is the brain. It also gives us a vision of the technology of the future.

This is the last post in this series. The series was about the mutual inspiration that brains and machines offer each other. I’m left with many thoughts and half-formed connections. A world of discovery remains at this interface.

Some References

Related