What really is a model? In short, it’s an agent’s understanding of the surrounding environment. In Markov processes, a model can be represented as probabilities of what will happen if the agent takes action A from state S.

Implementing a model into your reinforcement learning agent yields many benefits. The agent can perform lookahead and perform simulations in its head to try and predict what the best move is, without taking any real-world actions.

Learning a model can also be simpler than learning value functions, especially in environments with a lot of states. Take the game chess. There are 10^50+ possible states in chess, so a value function would take an unreasonable amount of time to compute. By instead learning a model, the agent can learn how the game itself works, and use any planning algorithm such as value/policy iteration to find a strategy. The downside here is that there is more computation involved in selecting an action.

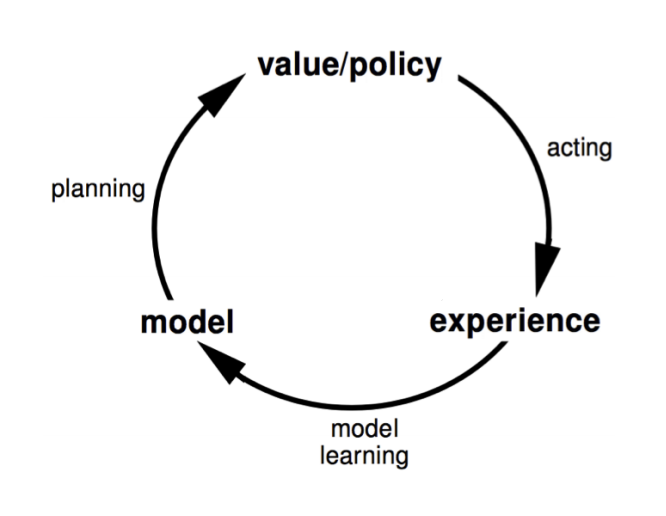

model-based learning

How is a model learned? Well, the idea is the same as learning a reward function. Every time an action is taken, we record which state we ended up in. We then use the ratios as the probability of transitioning to that state.

For simple tasks, having a table of states and actions will work just fine. However, for larger state spaces, a function approximator can be used instead, with the same techniques discussed earlier.

Combining model and model-free methods

So, model-free learning learns a policy directly from real-world interactions. In comparison, model-based learning learns a model of how the environment works, and comes up with a strategy based on simulated interactions.

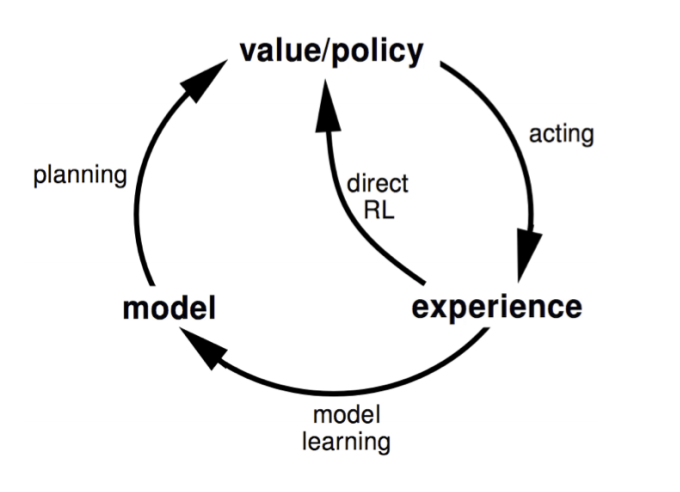

There’s actually a third option: Dyna is an idea that combines the best of both worlds. We still learn a model, but create the policy using both real and simulated data.

Dyna: learn policy from real and simulated interactions

A basic Dyna update would proceed as follows

-

Take an action in the real environment based on the current policy

-

Update value function Q(s,a) from the real experience using SARSA

-

Update the model’s transition probabilities from the real experience

-

Update Q(s,a) from simulated experience n times

-

Repeat

Why does this work? By keeping a model, we can make more efficient use of the data collected. If taking an action in the real environment is costly, Dyna allows us to make use of that data more than once.

Search methods

There’s another way we can utilize models to find a policy. Since we can simulate what will happen in the future, we can use forward search to look ahead and determine what action is best.

A key thing to note is we don’t need to solve the whole state space, only states that we will encounter from the current state onwards.

Like in the past, Monte-Carlo is the simplest example. Let’s say we’re at some state S. Using state S as the start state, we simulate a sequence of actions all the way until the terminal state, using the model we learned. If we do this many times for each possible action, and average the total return at the end, all that’s left is to act greedily and choose the action from the starting state that had the greatest average total return.

The problem here is that whatever policy we were using to simulate the model is static and doesn’t change. Monte-Carlo Tree Search fixes this problem.

In simple Monte-Carlo search, we performed a search and to find the best action at the start state. This is great and all, but it only helped us in one state. With Monte-Carlo Tree Search, we follow the same search as in Monte-Carlo search, but keep averages on state-action pairs for every pair we encounter, not only the starting state. Our simulation policy is then to act greedily towards the action that leads to the greatest average total reward. If it’s a new state, we can default to acting randomly in order to explore.

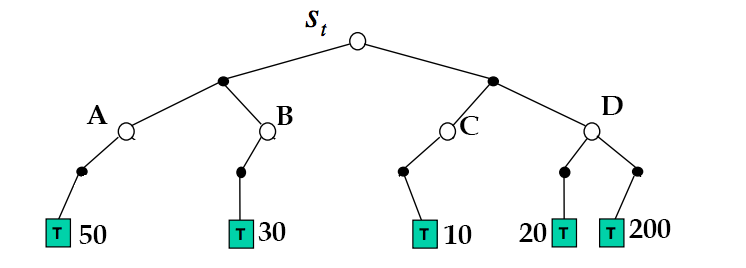

To make this concrete, say we’re in some starting state S. At first, we have no information, so we perform 100 iterations acting randomly until the terminal state, recording total rewards.

the model so far

In simple Monte Carlo search, all we would know is that going right from the starting state is better. However, in Monte Carlo Tree Search, we also know that going right from state D is better.

In practice, this is actually just the same as applying Monte-Carlo control to simulated experience that starts from the current state.

TD-learning works as well, especially in environments where the same state can be encountered twice in one episode.

Finally, there’s a method called Dyna-2 that combines this lookahead tree with the concept of using both simulated and real experience.

In Dyna-2, the agent holds long-term policy as well as short-term policy, as well as a model of the environment. The long-term policy is learned from real experience, using regular TD learning.

The short-term policy is computed at every state, using forward search to find the optimal action for this specific state.

The intuition here is that the long-term policy will learn general knowledge about the environment, while the short-term policy can search for specific results when starting from the current state.