It seems it may only be a matter of time before the best Go player on the planet is a computer. AlphaGo beat the European champion in Go and was driven by machine learning, a technology that has underpinned the recent major advances in artificial intelligence in computer vision, speech recognition and language translation.

Machine learning is a data driven approach to artificial intelligence. AlphaGo learnt how to play Go by many games played against itself, and by observing a large history of games played by professional players.

The end result is that by the time of its first match against the European Champion AlphaGo had already played many more games of Go than any human could possibly play in their lifetime. And since that win AlphaGo has been actively learning to improve itself. Relentlessly playing all day and all night in an effort to ready itself to play the world champion.

Our Data Delusion

This phenomenon isn’t restricted to AlphaGo. Our human-level performance in other domains is also driven by an unearthly amount of data. Our vision systems see way more labeled images than we require to recognize objects, our speech systems require many more words than we do to understand words. Our translation systems require many more examples of translated text than a human could read.

Assessment of the increase in the world’s data capacity.

So while we are making considerable progress on tasks which were once thought extremely difficult or impossible, the truth is that the progress is driven far more by the availability of data than an improvement in algorithms. Indeed, when we first tried to address tasks such as object recognition and language translation they would have been impossible if we had tried to apply state of the art methodologies to the data we had then. It is the explosion of data that has rendered them tractable.

Steam

The situation reminds me greatly of the early stage of the industrial revolution. Thomas Newcomen was born in the South West of England, an area well known, since Roman times, for tin mining. Mines need pumping out to keep water at bay. And in 1712 Newcomen invented the steam engine for doing that. His engine consisted of a large piston sitting on top of a boiler. The piston was alternatively filled with steam by the boiler, and then cooled through direct injection of water causing motion.

Coal

As it happened, Newcomen’s engine had relatively little effect at his local tin mines. They were so inefficient, that they were impractical. They were widely used but in coalfields, where they could be easily fueled.

This brings me to mind somewhat of the situation today: the major internet companies can profit from our current generation of inference engines because they are equivalent to the coalfields of yesteryear. They have enormous quantities of data readily available.

Medical Applications

The equivalent of the tin mines, and any other mine, is currently missing out. In application domains such as medicine we face challenges because firstly: the complexity of the system is much greater than speech, vision or even the game of Go. Our interventions are often at a biochemical level, and yet their manifestations occur at the global level of our health.

For rare or complex diseases: those that have causes driven by a combination of environmental and genetic causes, with the current set of inefficient models we will never have sufficient data for these complex models to learn what we need to know to diagnose early and deliver the cures we need.

Separate Condenser

The steam engine is far more associated in our minds with the name of James Watt, Watt made the steam engine practical by introducing the separate condenser. Rather than directly injecting water into the cylinder he sucked the steam out of the cylinder and cooled it separately.

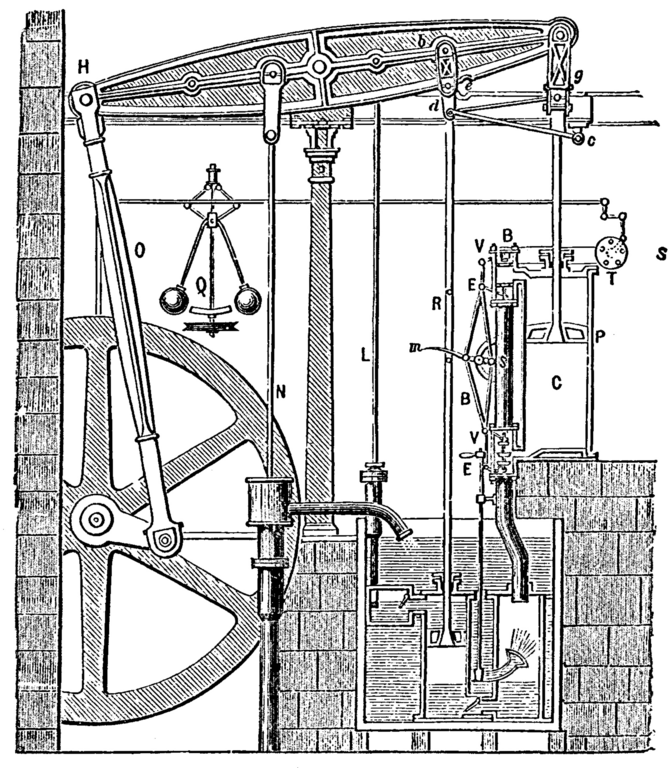

Schematic of James Watt’s engine with the separate condenser.

This was more efficient as the cylinder itself no longer had to go through cycles of heating and cooling. The resulting doubling in efficiency made the steam engine practical, not just for Cornish tin mines, but for railways and traction engines.

Intelligence

My definition of intelligence is the use of information to save energy.

Intelligent decision making implies that we assimilate the facts and make a decision that reduces our expenditure relative to actions we would have taken had we not had those facts. Under that definition, we can become more intelligent by either saving more energy with our resulting decisions, or by using less information.

In a very real sense there is currently a data efficiency deficit, just as large as the efficiency deficit present in Newcomen’s engine. Machine learning needs its separate condenser moment. What we require is a revolution in data efficiency equivalent to Watt’s separate condenser moment.

Function Composition and Deep Learning

Architecture of DeepFace, Facebook’s recognition system from their paper. See footnote for link.

In mathematics we can sometimes think of a function as a deterministic process. So we can think of deep learning as a combination of processes. Each individual process is composed together to create a more complex process. Presentation of data to the process allows us to apply a set of transformations to reach a result. Above is an example from Facebook’s DeepFace algorithm, the aim is to classify whether or not this is Calista Flockhart’s face.

In machine learning this is known as deep learning. For some authors it is related to the brain or a fundamental way of thinking about AI, but we can simply think of it as a sensible idea of applying a set of simple transformations to an image to built a complex transformation.

The challenge of machine learning is how to determine what these transformations should be. Each of the simpler deterministic transformations can actually have very many parameters. In the case of DeepFace there are more than 120 million parameters overall.

When we think of deep learning, we can think of any given data point passing through the deterministic processes like a ball falling through an early pinball machine (or a Pachinko machine). Each layer of pins is equivalent to a layer in the deep model.

The objective of machine learning, is to reconstruct the configuration of those pins in such a way that Calista’s face is correctly detected. Think of the face as a set of initial conditions, and the face passes through each process to emerge in modified form. The task of inference is to ensure that the right set of initial conditions lead to the right conclusion.

Our deep model is like a Pachinko machine, but one where we have control over the location of the pins. The objective in deep learning is to move the pins around in such a way that for the right set of initial conditions (as given by the image in our analogy), the correct result is achieved.

The parameters of the model are sometimes known as network weights. They are like the positions of the pins. So we can think of DeepFace having 120 million pins in their Pachinko machine.

We can think of the what the network ‘thinks’ about a particular pattern as being the left-right position of the ball as it falls through the network. Of course in reality, at each layer of pins this ‘thought’ is only one value. It’s one dimensional. Real deep networks have many many dimensions, so it’s like a Pachinko machine where the pins are in a high dimensional space, normally called a hyper-space. This means the networks ‘thoughts’ are higher dimension and more complex.

Deterministic Processes

The dominant technology of today assumes that the ball should take a fixed path through the network. The position of the ball at any layer in the Pachinko machine is known as the activation at that layer. As the ball drops its position is determined by the pins. In theory we can exactly say where the ball should be at any time, because each layer of Pachinko inovles only a ball hitting pins: it is a deterministic process.

The game of Pachinko involves trying to score high points by starting the ball with the right velocity using the plunger. This is difficult to do because the score is very sensitive to the starting position. But in effect the game is ‘understanding’ the initial velocity you give the ball and classifying it by giving it a score.

The challenge is to optimize the internal structure of the machine such that it gives the right answer (or label) for the right initial conditions. However, to do that, we need to explore the full range of initial conditons we wish to test: and for images that must be very many.

The clever part of convolutional neural networks is to structure the first set of layers for the machine such that aspects such as ‘invariances’ in the image are more easily learned. An invariance is the idea that a face in the image is the same face whether it is rotated or moved around in the image. Our own brains understand this easily, invariances are harder to impose in computers. The way deep networks do this is through clever design of the structure of the first part of the Pachinko machine.

The way in which most learning is done, is to present one image at the top of the Pachinko machine and see where the ball pops out. If it pops out in the wrong place, all the pins are moved a little bit to try change where the ball will emerge more to the right place.

The Problem

This works very well if you test the machine many times with all different subtle variations on the way you drop the ball in. You will eventually get the system right. But what if you only have a limited number of times you can drop the ball in?

You already know that small variations in input can account for quite large changes at the end. The Pachinko machine is complex and sensitive to small changes in the input. But to properly determine those sensitivities you need a lot of data.

An alternative is to ensure that your machine is robust to small changes in the initial conditions (or the activation further down the network). To do this you introduce stochasticity. Instead of modeling the machine as a set of deterministic processes, where the ball falls in exactly the same way each time, you model the machine as a layered set of stochastic processes.

You accept that very small changes in the way you drop the balls in at the top mean that we actually don’t know where the ball should be at any time because we don’t know precisely enough the locations of the pins or the initial state of the ball. And further, we’ll never have enough data to explore all those different states.

Stochastic Process Composition

We can get more efficient learning by considering all all the possible paths that the ball might take through the machine to end up at the right result. Instead of encouraging the machine to look at only one path, we encourage all those paths to lead to the right result.

Considering all the paths can make the model far more robust to small variations in the input. Imagine navigating through a forest where there are many paths. The difference between the two approaches is like the difference between ensuring there is one very well marked path to the right destination, or a group of different paths that all take you to the right direction.

This is a path integral interpretations of the system. We design a system in which we consider all possible paths the ball could take through the system. Even more strangely, we consider all possible configurations of the pins that should take you there at the same time.

This sounds very difficult, but such integrals are actually tractable for some classes of process (such as Gaussian processes). So if we make each layer out of a Gaussian process we can deal with that component on its own.

However, we want our deep models to involve many of these layers together, so that we can model complex things. To do this we compose stochastic models: effectively we stack them together, again, just like in the Pachinko machine. When we stack our simple processes together there are challenging issues in how we do the mathematics and implement the resulting algorithms.

What we do know is that for very large data, the stochastic approach we propose collapses to the deterministic approach of normal deep learning. Because in these cases the path integrals collapse to a single most likely path which becomes deterministic as we get more data. But for low data we can achieve much better efficiency.

The Algorithmic Challenge

The main algorithmic challenge is that solution of the path integral is far more challenging than finding just the best path. The best path needs us to do differentiation only, but looking through all paths requires integration, which is a greater challenge: particularly when it’s performed in the ‘hyper-space’ version of the Pachinko machine that we need. The mathematical operation is known as convolution, and it is only possible to do it exactly for simple systems.

A Way Forward

It took a long time for the theory of thermodynamics to catch up with Watt’s implementation of the seperate condenser, but a thorough understanding of thermodynamics was vital to developing our modern world.

It turns out that there is a strong mathematical connection between the path integrals we need for efficient intelligence and the theory of thermodynamics which is used to explain why Watt’s separate condenser made the steam engine more efficient.

One mathematical way forward is known as the ‘variational method’. This involves converting the difficult integrals into different, but easier, optimisation problems. The approach is not exact, but will often perform much better than the dterministic approach. This is known as variational learning. If we construct efficient variational algorithms then we can implement deep models on small data sets.

It was also variational methods that finally unpicked the underpinnings of our theory of heat. From this study arose concepts such as entropy which appear directly in our integral based formulations of deep models.

One thing we know is that, by thermodynamic analogy, it is best to keep your Pachinko machine as ‘hot as possible’ (or as uncertain as possible) whilst constraining it to give the right answer on average. That makes it more robust to variations on the input. In physics this approach is known as the maximum entropy principle.

The next generation of data efficient learning approaches relies on us developing new algorithms that can propagate stochasticity or uncertainty right through the model.

There is a large and growing community of researchers implementing and deriving these algorithms. They are mathematically more involved than the standard approaches, but without them, many of us will be in the position of the Cornish tin miners: we will not benefit from the advantages of wide data availability because of our own failings in data efficiency.

So in the end, our efficiency demands come down to a question of handling uncertainty. James Watt’s efficiency gains arose through ensuring his engine’s piston remained as hot as possible. For the piston to close the hot steam was sucked out and condensed separately. This enabled the piston to operate hotter delivering the required efficiency.

In probabilistic and stochastic approaches to deep learning we have to perform the same trick. The model itself needs to be kept as hot as possible: then when the data is insufficient to constrain the operation of our model we need to embrace the uncertainty, not quench it. Our separate condenser would allow the high temperatures to be retained in the learning machine while it cycles through the data. That will ensure that the the full space of plausible modes of operation is explored and our inferences will retain the necessary robustness even when data is scarce.