· Read in 10 minutes · 1800 words · collected posts ·

We all make mistakes, and as is often said, only then can we learn. Our mistakes allow us to gain insight, and the ability to make better judgements and fewer mistakes in future. In their influential paper, the neuroscientists Robert Rescorla and Allan Wagner put this more succinctly, ‘organisms only learn when events violate their expectations’ [1]. And so too of learning in machines. In both brains and machines we learn by trading the currency of violated expectations: mistakes that are represented as prediction errors.

We rely on predictions to aid every part of our decision-making. We make predictions about the position of objects as they fall to catch them, the emotional state of other people to set the tone of our conversations, the future behaviour of economic indicators, and of the potentially adverse effects of new medical treatments. Of the multitude of prediction problems that exist, the prediction of rewards is one of the most fundamental and one that brains are especially good at. This post explores the neuroscience and mathematics of rewards, and the mutual inspirations these fields offer us for the understanding and design of intelligent systems.

A reward, like the affirmation of a parent or the pleasure of eating something sweet, is the positive value we associate to events that are in some way beneficial (for survival or pleasure). We quickly learn to identify states and actions that lead to rewards, and constantly adapt our behaviours to maximise them. This is an ability known as associative learning and leads us, in the framework of Marr’s levels of analysis, to an important computational problem: what is the principle of associative learning in brains and machines?

As modern-day neuroscientists, the tools with which we can interrogate the function of the brain are many: psychological experiments, functional magnetic resonance imaging, pharmacological interventions, single-cell neural recordings, fast-scan cyclic voltammetry, optogenetics; all provide us with a rich implementation-level understanding of associative learning at many levels of granularity. A tale of discovery using these tools unfolds.

It begins with the famous psychological experiments of Pavlov and his dogs. Pavlov’s experiments identify two types of behavioural phenomena—Pavlovian or classical conditioning, and instrumental conditioning—which in turn identify two distinct reward-prediction problems. Pavlovian conditioning exposes our ability to make predictions of future rewards given a cue (like the sound of a bell that indicates food); instrumental conditioning shows we can predict and select actions that lead to future rewards. When functional MRI is used to obtain blood oxygen-level dependent (BOLD) contrast images of humans performing classical or instrumental conditioning tasks, one particular area of the brain, the striatum, stands out [2].

The striatum is special since it is a major target of the neurotransmitter dopamine, and leads to the sneaking suspicion that dopamine plays an important role in reward-based learning. This suspicion is substantiated through a series of pharmacological experiments using neuroleptic drugs (dopamine antagonists). Without dopamine the the normal function of associative learning is noticeably impeded [3]. Neurons in the brain that use dopamine as a neurotransmitter are referred to as dopaminergic neurons. Such neurons are concentrated in the midbrain and are a part of several pathways. The nigrostriatal pathway links the substantia nigra (SN) with the striatum, and the mesolimbic pathway links the ventral tegmental area (VTA) with the forebrain (see image).

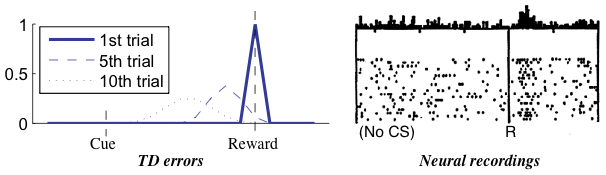

When single-cell recordings of dopaminergic neurons are made from awake monkeys as they reach for a rewarding sip of juice, after seeing a cue (e.g., a light), there is a distinct dopaminergic response [4]. When this reward is first experienced, there is a clear response from dopaminergic neurons, but this fades after a number of trials. The implication is that dopamine is not a representation of reward in the brain. Instead, dopamine was proposed as a means of representing the error made in predicting rewards. A means of causally manipulating multiple neurons is needed to verify such a hypothesis. Optogenetics offers exactly such a tool, and provides a means stimulating precise neural-firing patterns in collections of neurons and observing them by creating a light-activated ion channel. Using optogenetic activation, dopamine neurons were selectively triggered in rats to mimic the effect of positive prediction error, and allowed a causal link between prediction errors, dopamine and learning to be established [5].

And so goes the reward-prediction error hypothesis: ‘the fluctuating delivery of dopamine from the VTA to cortical and subcortical target structures in part delivers information about prediction errors between the expected amount of reward and the actual reward’ [6]. There isn’t unanimous acceptance of this hypothesis and incentive salience is one alternative [7]. There is a need for a review that includes the recent evidence that has accumulated, but the existing surveys remain insightful:

The reward-prediction error hypothesis is compelling. With support from ever-increasing evidence, we have established the computational problem of associative learning in the brain, an algorithmic solution that predicates learning on prediction errors, and an implementation in brains through the phasic activity of dopaminergic neurons. How can this learning strategy can be used by machines?

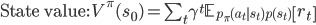

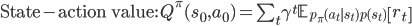

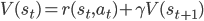

Reinforcement learning—the machine learning of rewards—provides us with the mathematical framework with which we can understand and provide an algorithmic specification of the computational problem of associative learning. As agents in the world, we observe the state of the world s, can take an action a, and observe rewards r, and we do this continually (a perception-action loop). In reinforcement learning the associative learning problem is known as value learning, and involves learning about two types of value function: state value functions and state-action value functions.

Simplified perception-action loop.

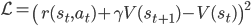

These equations embody our computational problem:

Like in classical conditioning, the state value function  allows us to predict future rewards when the right stimuli are present. Like in instrumental conditioning, the state-action value function

allows us to predict future rewards when the right stimuli are present. Like in instrumental conditioning, the state-action value function  allows us to select the next action that will allow us to obtain the most reward in future.

allows us to select the next action that will allow us to obtain the most reward in future.

In general, there are three ingredients needed for a machine learning solution of a learning problem: a model, a learning objective and an algorithm. There are many types of models we can use to represent value functions: a non-parametric model that maintains a table of values for every state explicitly, a nearest neighbour method or Gaussian process; or a parametric model with parameters  , such as a deep neural network, a spline model or other basis-function methods.

, such as a deep neural network, a spline model or other basis-function methods.

If we take one step in our environment and move from state  to state

to state  , the value function should satisfy the following consistency criterion:

, the value function should satisfy the following consistency criterion:

The self-consistency property of the value function is what we use to obtain our learning objective. The simplest way to do this is to use a measure of discrepancy between the two sides of the equation. For the state value function, we get:

This is known as the squared Bellman residual [8], and importantly, introduces a prediction error that will drive reward-based learning.

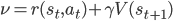

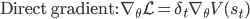

We derive a learning algorithm by gradient descent on this objective function. Consider state-value estimation; we obtain two types of descent algorithm, depending on how we treat the term  , the right-hand side of the Bellman consistency equation.

, the right-hand side of the Bellman consistency equation.

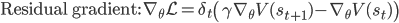

As a result, we obtain two update rules for gradient descent depending on which approach we take, a direct gradient and a residual gradient:

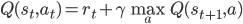

The term  is the temporal difference (TD)—an error in the prediction of rewards at two time points—that quantifies the extent to which our expectations (value predictions) have been violated. Early in learning, our TD errors will be high, and as we learn the TD error fades, shadowing the response of dopamine in the brain (see image).

is the temporal difference (TD)—an error in the prediction of rewards at two time points—that quantifies the extent to which our expectations (value predictions) have been violated. Early in learning, our TD errors will be high, and as we learn the TD error fades, shadowing the response of dopamine in the brain (see image).

Reward prediction errors are high when first encountered, but diminish over time. [Niv, 2009]

We have derived the famous temporal difference learning algorithm in reinforcement learning [9], which is the stochastic update rule for parameters of a value function using gradients of the squared Bellman residual. And all this can be repeated for the state-action value function, yielding the Q-learning algorithm. This is a powerful mathematical framework in which to derive a range of more sophisticated reward-based learning systems:

The computational problem of associative learning in the brain is paralleled by value learning in machines. Both brains and machines make long-term predictions about rewards, and use prediction errors to learn about rewards and how to take optimal actions. This correspondence is one of the great instances of the mutual inspiration that neuroscience and machine learning offer each other, more of which we’ll explore in other posts in this series.

Some References

Related