|

On a table infront of you are sixteen gold nuggets.You have been told that you can take any two of them as a gift.As is human nature, you wish to take the two heaviest nuggets. |

You have been told that you can take any two of them as a gift.

|The nuggets are all random natural shapes.You are not skilled enough to estimate their individual weights, nor are you able, by hand, to determine their relative masses.Even though each of the nuggets is pure gold, they contain voids and holes so that you can’t judge their weights by volume or shape. You will have to go by weight alone.| |

|

You are not skilled enough to estimate their individual weights, nor are you able, by hand, to determine their relative masses.

| |All is not lost, however, because you possess a pair of perfect balance scales.These scales will indicate which is the more massive of any items placed in the pans in opposite sides.How can you use these scales, and only these scales, to identify the two heaviest nuggets?|

|All is not lost, however, because you possess a pair of perfect balance scales.These scales will indicate which is the more massive of any items placed in the pans in opposite sides.How can you use these scales, and only these scales, to identify the two heaviest nuggets?|

These scales will indicate which is the more massive of any items placed in the pans in opposite sides.

|What is the smallest number of weighings needed to be able to identify the two heaviest nuggets (and what is your strategy)?| |

|

Weighings

| |If you’ve seen coin balance puzzles before you might be tempted to start by initially putting half the nuggets in one pan, and half in the other, but in this case, that will not help you. Each of the nuggets has a distinct weight (and you have no idea on their variance); just because a collection of nuggets tips their side down, it does not mean that the heaviest nuggets are in that pan. It could be that you grouped the heaviest nuggets with the lightest nuggets, and their combined weight is less than a collection of some of the medium massed nuggets.We need a way of finding, not just the heaviest, but also the next heaviest. Obviously we’d like to do this by performing the smallest number of weighings.We need to ensure that whatever strategy we employ will work no matter how the masses of nuggets are distributed.|

|If you’ve seen coin balance puzzles before you might be tempted to start by initially putting half the nuggets in one pan, and half in the other, but in this case, that will not help you. Each of the nuggets has a distinct weight (and you have no idea on their variance); just because a collection of nuggets tips their side down, it does not mean that the heaviest nuggets are in that pan. It could be that you grouped the heaviest nuggets with the lightest nuggets, and their combined weight is less than a collection of some of the medium massed nuggets.We need a way of finding, not just the heaviest, but also the next heaviest. Obviously we’d like to do this by performing the smallest number of weighings.We need to ensure that whatever strategy we employ will work no matter how the masses of nuggets are distributed.|

We need a way of finding, not just the heaviest, but also the next heaviest. Obviously we’d like to do this by performing the smallest number of weighings.

Solution

With sixteen nuggets, it’s possible to find the two heaviest with just eighteen weighings. If you want to give it a go yourself, stop reading now, and dig out a pencil and paper. If you think you’ve got it, or just want to see the answer, continue reading …

First we need to find the heaviest

Everytime we perform a weighing we gain a piece of information. If we place a single nugget on each side of the balance, we can determine which of them is the heaviest. Weight has transitive properties. This means that if we have three nuggets {A,B,C} and A is heavier than B, and B is heavier than C, then we also know that A is heavier than C. (Not all properties in life are transitive. If Nick likes Lucy, and Lucy like Bob, it does not have to mean that Nick will also like Bob. Probably the most famous non-transitive relationship is the game of Rock, Paper, Scissors).

| |As well as being transitive, weighings are also repeatable. Each time we perform the same experiment, we will get the same result.Think of each weighing as a contest: Two nuggets go in, and one comes out (the winner).By definition, the heaviest nugget is unbeatable. It will win every contest it enters.|

|As well as being transitive, weighings are also repeatable. Each time we perform the same experiment, we will get the same result.Think of each weighing as a contest: Two nuggets go in, and one comes out (the winner).By definition, the heaviest nugget is unbeatable. It will win every contest it enters.|

Think of each weighing as a contest: Two nuggets go in, and one comes out (the winner).

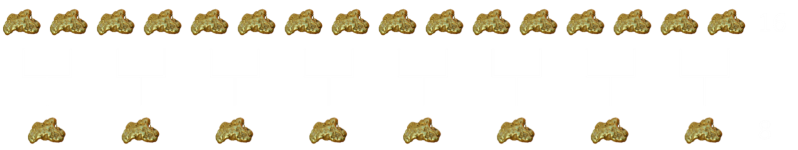

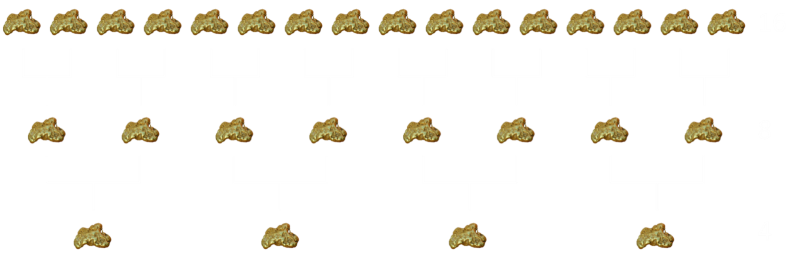

The first step is to pair the sixteen nuggets into eight groups of two and weigh each of these two nuggets against each other. Each of these contests will have one winner. We have reduced the number of possible candidates by half. The heaviest nugget must be one of the eight first round contest winners.

This has taken eight weighings. We now have a self-similar problem but with half the number of nuggets. We can pair these eight nuggets against each other and in four more weighings reduce the possible number down to four. Because the heaviest nugget will always win, it must be one of these four.

This has taken us twelve weighings, and we’ve reduced the number of nuggests down to four. Pairing these off again for two more rounds (a total of three more weighings), and we will have determined which is the heaviest nugget.

Note - We have not had to weigh each nugget against every other nugget; we have relied on the transitive property to only graduate the heaviest of each contest. If one nugget beats a second nugget, it means it would also have beaten any other nugget that the second nugget beat.

It has taken us fifteen weighings to find the heaviest nugget. You can probably see that we’re halving the number each time. If the number of nuggets is a power of two, then it works out nicely. If there are more than a natural power of two then, just like a single elimination bracket soccer tournament, there will need to be bys.

Second Heaviest

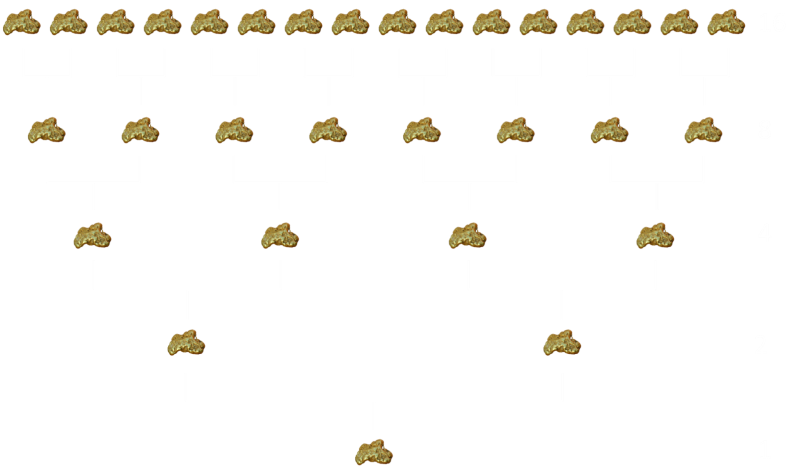

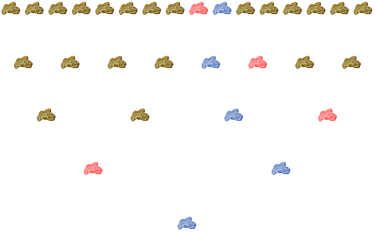

|We now know the heaviest nugget. Without loss of generality, let’s imagine how it might have progressed through the weighings. In the diagram to the right, the heaviest nugget is shown in blue.It wins every challenge.| |

|

It wins every challenge.

| |The second heaviest nugget will also win competitions. It will win all competitions with the exception of it’s fight with the heaviest nugget; the only nugget that can knock it out is the heaviest one.We, therefore, only need to look at the competitions in which (what we now know is the heaviest) was involved with. These are shown in red in the diagram in the left.The second heaviest nugget must be one of the four red nuggets (though we do not know which one), and we don’t even need to care what happened before it got to the challenge with the heaviest nugget.|

|The second heaviest nugget will also win competitions. It will win all competitions with the exception of it’s fight with the heaviest nugget; the only nugget that can knock it out is the heaviest one.We, therefore, only need to look at the competitions in which (what we now know is the heaviest) was involved with. These are shown in red in the diagram in the left.The second heaviest nugget must be one of the four red nuggets (though we do not know which one), and we don’t even need to care what happened before it got to the challenge with the heaviest nugget.|

We, therefore, only need to look at the competitions in which (what we now know is the heaviest) was involved with. These are shown in red in the diagram in the left.

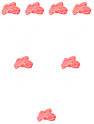

|We can now run another bracket with these four ‘semi-finalists’ candidates to see which of these is the heaviest.As there are only four of them, we can find the winner of this competition in just three weighings.The total number of weighings required to find both the 1st and 2nd place is 15 + 3 = 18.| |

|

As there are only four of them, we can find the winner of this competition in just three weighings.

Putting it all together

We now have the complete solution to this problem. We keep pairing off nuggets on each round to halve the number left until we find the heaviest. Once we know this, we find all the potential candidates by for second heaviest by running a ‘play-off’ with just the nuggets that competed (and were eliminated) by the heaviest.

For sixteen nuggets, this takes a total of eighteen weighings.

What happens if we wanted to find the top three heaviest nuggets, or the top four? … taken to the limit, how about we determine the weight order of all of them? We can do this by stack-ranking all nuggest by weight in order. This problem is what computer scientists call sorting.

Sorting is one of the building blocks of computer programming and considerable research has been performed into the analysis of the different techniques that can be used. There is a theoretical limit as to how quickly sorting can be performed (sufficient comparissons need to be performed to help distinguish any combination of starting states), and different sorts have different characteristics.

Some sorts are efficient if the items to be ordered are already pretty well sorted (in the nugget example, if you used common sense and tried to put them in approximately the correct order before starting some sorts can take advantage of this). In this nugget puzzle, each item has a distinct weight, but if you were sorting items that may have the same value (such as playing cards in a deck), it might be important to you to keep the ordering of the suits of the cards in the way they appeared as well as numerically ordered, othertimes, it might be good enough to simply get the cards in numeric order.

For a comprehensive list of sorting algorithms, their pros and cons, memory use, check out this article.

Without delving too deep in to the theory (see link above for that), here are descriptions of a few of the more commonly used sorting techniques and how these could be used to sort the nuggests.

Selection Sort

This is probably the easiest sort to understand (it’s also very inefficient). We start with the first nugget, and compare it, in turn, with every other nugget in the pile, keeping as we go, the heaviest we find. After we’ve been through all the nuggets we’ll have found the heaviest. We put this aside, knowing that this is the heaviest, and start again, but this time there is one less nugget. We walk through all the remaining nuggets and find the heaviest now left (by comparing all the way along); this is then placed in the ‘sorted’ pile adjacent to the last found heaviest, and we repeat the exercise once again, this time with one fewer nuggets …

This process continues until the next to last item which, after it has been placed, will stop the process, because all the others heavier have already been removed in order, and the one left will have to be lightest.

Even if the nuggets were already in weight order, a selection sort technique would still blindly plow through with the same number of transactions and comparissons. Also, even though it passes through the nuggets multiple times, on each pass, it selfishly only deals with trying to find the answer to what it currently wants (which is the heaviest of those left).

Insertion Sort

The next sort to consider is the insertion sort. This is subtly differnet from the selection sort in that it places each newly picked nugget in the current correct sorted position as it goes along. There is a ‘sorted’ pile (initially empty), and an unsorted pile (initially all the nuggets). We take the first nugget from the unsorted pile, and since this is the first we’re done with this round, and it is the first nugget in our sorted pile.

We then take the next nugget from the unsorted pile. We walk through the sorted pile, comparing as we go, until we find the correct place to insert it. When it’s the second found nugget, it either goes before, or after the first nugget. We then pick up the next nugget from the unsorted pile and scan through the sorted pile looking for correct place to insert it. Either the nugget is inserted at the correct place in the sorted pile (shuffling others down as we go), or it’s added right at the end (if it’s the lightest we’ve seen).

This process of picking up the next nugget and inserting it into the correct place, builds a sorted list as we go along. Each newly added nugget keeps the list in a sorted state.

If the nuggets are already in order, an insertion sort whips through the pile very quickly with each nugget simply being added to the end of the list as it is being built up (making it pretty quick). The worst case, however, is if the nuggets are in reverse size order. In this case, in each pass everything has to be shifted down one place before the latest can be placed in the correct place.

Bubble Sort

Bubble sort also easy to describe. Like insertion sort, if the ordering is already pretty close to optimal, it can itelligently terminate quickly. Bubble sort works by constantly running through the nuggets and comparing each nugget with the next nugget in the list, swapping if appropriate. If it gets to the end, it starts again at back at the begining. It repeats this process over and over until no swaps need to be made. If the entire list can be passed through without any swaps needed, it is in order.

The sort is called a bubble sort (sometimes a sinking sort), because the smaller items ‘float’ up to the top, and the heavier items ‘sink’ to the bottom. However, an item only moves one position on each pass. This means that if the order is inverted at the start, this is the worst case and each item has to switch ends.

Quick Sort

This is the hardest of the simple sorts to describe, but it is one of the better sorts and is commonly the ‘go to’ sort technique used by default.

The key to this sort is the use of a pivot. One of the nuggets is chosen as a pivot. All the nuggets that are heavier than the pivot are moved to the left of the pivot, and those that are lighter are moved to the right. (If you think about this for a second you will see that this means that the pivot now has to be in the correct position; all the nuggets heavier are on one side, and all those lighter are on the other side).

Now what we have now is two smaller, self-similar problems (with the pivot in between). We can perform the same algorithm again to both sides of the pivot; we find another pivot in each side, and move nuggets greater than this pivot to one side, and those lighter to the other. We can then recurse down, dividing-and-conquering each side. The sets each time get smaller and smaller in size until they reach just one (or zero) elements in length, which don’t need sorting. Problem solved!

Visualization

| |A picture speaks a thousand words, so many pictures speak many thousands of words.Here is an awesome web page that visualizes the sort algorithms described above (and many others). For each algorithm you can see how progress is made, and how the different algorithms have different advantages and disadvantges based on the initial starting conditions.|

|A picture speaks a thousand words, so many pictures speak many thousands of words.Here is an awesome web page that visualizes the sort algorithms described above (and many others). For each algorithm you can see how progress is made, and how the different algorithms have different advantages and disadvantges based on the initial starting conditions.|

Here is an awesome web page that visualizes the sort algorithms described above (and many others). For each algorithm you can see how progress is made, and how the different algorithms have different advantages and disadvantges based on the initial starting conditions.

You can find a complete list of all the articles here. Click here to receive email alerts on new articles.

Click here to receive email alerts on new articles.