Bayes’ Rule is one of the fundamental Theorems of statistics, but up until recently, I have to admit, I was never very impressed with it. Bayes’ gives you a way of determining the probability that a given event will occur, or that a given condition is true, given your knowledge of another related event or condition. All the examples that I’ve read or heard about seemed somewhat contrived and unrelated to the sorts of data analysis I was interested in. But it turns out there’s also an interpretation of Bayes’ Theorem that’s not only much more geometric than the standard formulation, but also fits quite naturally into the types of things that I’ve been discussing on this blog. So in today’s post, I want to explain how I came to truly appreciate Bayes’ Theorem.

But rather than start with the statement of Bayes’ Theorem, I want to use an old math teacher trick (which I realize many students hate) of trying to derive it from scratch, without stating what we’re trying to derive. Rather, we’ll start by modifying a problem that I described in an earlier post on probability distributions.

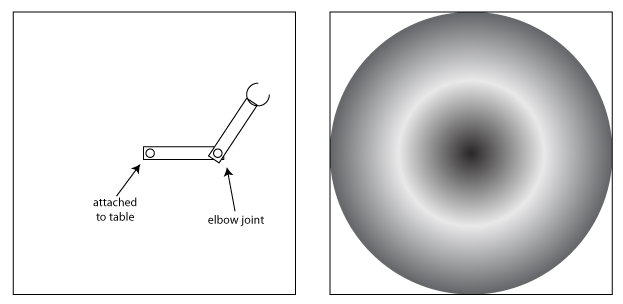

Lets pretend we have a robot arm with two joints: The first is fixed to the center of a table and spins horizontally. There’s a bar from this first joint to the second joint, which also spins horizontally and is attached to a second bar. The two bars are the same length, as shown on the left in the Figure below. The game is to randomly pick a pair of angles for the two joints, then try to guess the x and y coordinates of the hand at the end of the arm. As I described in the earlier post, we can think of the (density function of the) probability distribution of all the possible (x, y) coordinates, and it would look something like what’s shown on the right of the Figure. Here, darker colors indicate larger values of the function.

In the earlier post, we determined that the best place to predict that the hand would be is near the center, since that’s where the probability density is highest. But now we’re going to modify the game a bit: What if each time after spinning the wheel, we are told something about the x-coordinate; either its exact value or a small range. Then how would that change our prediction? Note that if we’re given the exact x-value and asked to predict y, then this is essentially the regression problem except that the probability distribution doesn’t look anything like the one we used in the post on regression.

But lets start with the case where we’re given a range, for example if we knew that the x-value was between 1/4 and 1/3. Then the probability of getting any point with an x-value outside this range would be zero, so the probability density that we would use to guess the y-value would be equal to zero for all points with x-values outside this range. So it would look something like the Figure on the right.

But lets start with the case where we’re given a range, for example if we knew that the x-value was between 1/4 and 1/3. Then the probability of getting any point with an x-value outside this range would be zero, so the probability density that we would use to guess the y-value would be equal to zero for all points with x-values outside this range. So it would look something like the Figure on the right.

But dropping those values to zero isn’t enough to get the new distribution; the problem is that when we add this restriction on x, the probability of any point with an x-value in the correct range will increase. The question is: By how much will they increase?

In order to answer this question, we need to look more closely at what the probability density function really means. The first thing to note is that the value of the probability density function at a point is not the probability of choosing that point. In fact, the probability of picking any one point is zero, since there are infinitely many possible x and y values.

In order to understand the meaning of the probability density function, we need to use integrals, but (as usual) we can avoid much of the technical details by describing things in terms of the geometry that underlies those integrals. In particular, we’re going to think of our probability density function as describing the elevations of a mountain whose base is the square in which our robot arm rotates. But it won’t be a normal looking mountain – because of the way the density function looks, it’ll have a high peak in the middle, surrounded by a deep moat, then a high circular ridge (shorter than the central peak) around the outside.

I’ve attempted to draw this on the left, but you’re probably better off using your imagination to picture it. Once we’ve transformed our density function into this mountain, we can replace the word “integral” with “volume” and we’ll be able to calculate some probabilities.

I’ve attempted to draw this on the left, but you’re probably better off using your imagination to picture it. Once we’ve transformed our density function into this mountain, we can replace the word “integral” with “volume” and we’ll be able to calculate some probabilities.

Now, as noted above, if we pick one specific point, the probability that the hand will end up there is zero. However, if we pick a particular region A of the square, such as a rectangle defined by a range of x-values and a range of y-values, then there may be a non-zero probability that the hand will stop within A. (Though everything I will say below also holds true for more complex shapes A, as well as for shapes in higher-dimensional probability spaces.) In particular, the density function is defined specifically so that the probability will be equal to the volume of the part of the mountain above the shape A.

In other words, if we were to take a band saw to the mountain, following the outline of A, then the volume of the piece that we cut out would be equal to the probability of the robot’s hand stopping within that region. We’ll call this volume/probability P(A).

So, not only is the value of the probability density function at a point not the probability of getting that point (since it’s always zero), the value of the density function at a point doesn’t even need to be less than one. In particular, if there is a region A with a small area but a very high (though still less than 1) probability, the values of the density function would need to be very high in order to get the appropriate volume.

If we choose region A to be the entire square then P(A) = 1 because the arm is constrained to stay within that region. So the volume of the entire mountain is 1. If we choose a smaller region A, and an even smaller region B contained in A, then we’ll get a piece with smaller volume P(B) < P(A), and thus lower probability as we would expect.

| But now lets return to the original question of how to modify our density function after we’ve narrowed down the set of possible outcomes to a smaller range A of x-values. This function will define a different mountain that is low and flat everywhere outside of A, but has the same elevations as the original within* A, as on the left in the Figure below. We want to modify this function to give us a new probability density defining a volume function which we’ll write *P( | A)* where * can be any region of the square. Since we know the robot hand landed in A, the overall probability, i.e. the volume *P(A | A) *of the new mountain, should be 1. However, since all we did was flatten the parts of the mountain outside the region, its volume is initially quite a bit less than 1. |

| In order to get the correct volume, we’ll need to scale the function up, i.e. multiply each value of the function by a constant k. The resulting function will define a mountain more like the one shown on the right above. For any region B contained in A, we’ll have *P(B | A) = kP(B).* Since we want *P(A | A) = 1 = P(A)/P(A), the only possible value for k* is 1/P(A) and we get *P(B | A) = P(B)/P(A).* |

This is the case when the region B is contained in A. But what if it isn’t? For example, if we want to predict a range of y-values once we know the robot hand is in a certain range of x-values, then A will be a vertical strip of the square, and B will be a horizontal strip of the square, with the two intersecting in a smaller rectangle. (But as I noted above, we could just as easily let A and B be arbitrary blobs in the square or even blobs in a higher-dimensional space, but lets not get too complicated…)

| So, if we want to calculate *P(B | A)* in this case, we need to consider two parts of B separately: The density function above the part of B that is outside of A will all get flattened to zero, so *P(B | A)* is completely determined by the part of B inside of A, i.e. the intersection A ∩ B. In other words, we have *P(B | A) = P(A ∩ B)/P(A). Note that there’s no difference between A* and B in this formulation, so we also have *P(A | B) = P(A ∩ B)/P(B).* We can solve both equations for P(A ∩ B) to get *P(B | A)P(B) = P(A ∩ B) = P(A | B)P(A). Finally, if we divide both sides by P(B)*, we get Bayes’ Theorem: |

| *P(B | A) = P(A | B)P(A)/P(B)* |

| Of course, for the problem we started out with, the original equation *P(B | A) = P(A ∩ B)/P(B) may sometimes be more useful. But in the standard setting of Bayes’ Theorem, *P(A ∩ B) is the probability that both events happen (or both statements are true) so it might be harder to calculate. |

For extra credit, take a minute to think about how you might calculate the probabilities of different y-values if we knew the exact value of x rather than a range. I’ll give you two hints: First, note that the probability density function over the vertical line defined by a single x-value defines a single-variable function like you might find in Calculus I and II, and there is some area (rather than a volume) below this function. Second, note that you can take A to be a small rectangular strip around the line defined by the x-value, calculate its volume, then make the strip smaller and smaller and take a limit.

But this post is already long enough, and I expect that most of my readers either don’t want to read about limits, or would rather work it out themselves. (For me, it’s both.) So I’ll leave it there.

Like this:

Like Loading…

Related