Let’s imagine that I have ten old computer circuit boards. Eight are in perfect condition, and two are defective.

Image: Konstantin Lanzet

I want to determine which are the two defective boards, and the only tool I have is an antiquated testing machine. To use the machine, I have to insert exactly three circuit boards, then push a test button. The test machine always gives a result and identfies a ‘defective’ board. Knowing what I do about the peculiarities of this test machine, here’s what could happen:

|- If exactly one of the boards is defective, the machine correctly identifies the defective board.- If two of the boards are defective, the machine randomly (and correctly) identifies one of the defective boards.- If none of the boards are defective, the machine, bogusly, identifies one of the good boards (at random) as bad. Because we know there are only two defective boards, there will never be a scenario where three defective boards are in the machine at the same time.| |

|

So, whatever the composition of states of boards inserted into the test machine, on every test, one circuit board will be classified as defective (sometimes correctly, but possibly incorrectly).

The test machine is agnostic of the ordering of the cards so there is no information that can be gained form knowing which slot any card was in when the test was run. Also, there is no information about the bias, periodicity, skew, or affinity when a card is selected at random, so any strategy involving repeating the same test multiple times and averaging the results is bogus.

Can you devise a strategy that will allow you to determine which two boards are defective? What is the smallest number of tests needed to perform this task? |Show Solution|Think about it for a while, then, when you think you have it, click the button to see a solution.|

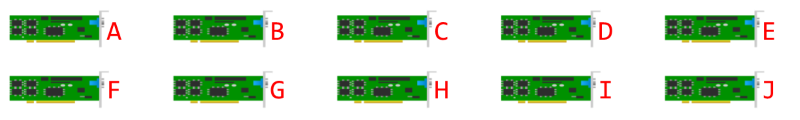

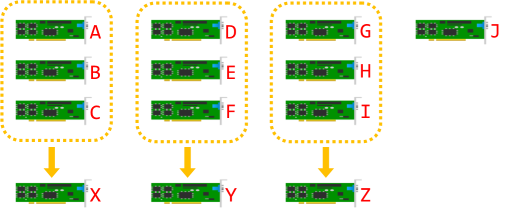

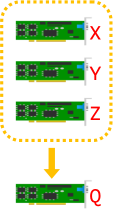

Let’s label our cards A-F. The first thing to do it create three groups of three {A,B,C}, {D,E,F}, {G,H,I}, and a singleton {J}. We test each group of three. We’ve run three tests so far.

There will be one card identified as ‘defective’ from each test, and we’ll call these {X,Y,Z}. Because we know there are a total of two defective cards, we know that at least one of these three cards is broken (we’ve tested nine out of ten cards). There are two possible scenarios:

-

If J is defective, then just one of {X,Y,Z} has to be defective.

-

If J is not defective, then (at least) one of {X,Y,Z} is defective, as is one additional {A-I}.

|

Either way, we know that at least one of {X,Y,Z} is defective, so let’s run a fourth test on these to get one we can guarantee is defective.We’ll call the result out of this test Q. We know that Q has to be one of the defective boards.So far so good. Now it gets a little more complicated (but thankfully not much more). |

We’ll call the result out of this test Q. We know that Q has to be one of the defective boards.

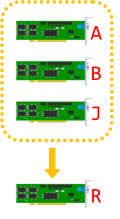

|We know which set of three that Q came from, and also which card it was from that set. Let’s pretend that Q was X, so came from set {A,B,C}, and let’s pretend it was card C (from symmetry, we’ll see this solution is general).If both defective cards were in the same triplet, then A or B is the other defective card.The other possibility is that the other defective card must be either {Y,Z,J} (One of the other cards from the first batch of tests, or the singleton which has not yet been tested).We know the second defective card is in the set {A,B,Y,Z,J}.The next test we’ll run is {A,B,J} and we’ll call this result R. This is test five. (This will bubble up the defective card, if it is present).| |

|

If both defective cards were in the same triplet, then A or B is the other defective card.

We know the second defective card is in the set {A,B,Y,Z,J}.

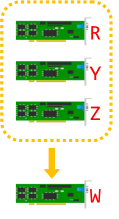

| |The final test will be {R,Y,Z}. One of these must be the second defective card!The two defective cards are Q and W. It has taken us six tests.|

|The final test will be {R,Y,Z}. One of these must be the second defective card!The two defective cards are Q and W. It has taken us six tests.|

The two defective cards are Q and W. It has taken us six tests.

There’s a related problem floating around the internet in which you have to find the three fastest horses out of 25, without using a stopwatch. You do this by running a series of races of five horses against each other (the maximum a track can allow). The solution strategy is similar to the solution above. The difference between the horse problem and the problem above is there is no randomness, but you do get the added information from the ordinal ranking results from each race.

Finally, there is a proverbial collection of problems about finding counterfeit gold coins, in the minimum number of weighings, using just a balance beam and placing coins on each side. Sometimes the counterfeit coins are heavier, sometimes they are lighter, sometimes you aren’t told either way; it depends on the problem. Sometimes there is more than one counterfeit coin. There are entire books written about these balance problems.

You can find a complete list of all the articles here. Click here to receive email alerts on new articles.

Click here to receive email alerts on new articles.