|

We didn’t get a White Christmas in Seattle this year.

| |We didn’t get a White Christmas in Seattle this year.Let’s do the next best thing, let’s generate fractal snowflakes!What is a fractal? A fractal is a self-similar shape.Fractals are never-ending infinitely complex shapes. If you zoom into a fractal, you get see a shape similar to that seen at a higher level (albeit it at smaller scale). It’s possible to continuously zoom into a fractal and experience the same behavior.Two of the most well-known fractal curves are Hilbert Curves and Koch Curves. I’ve written about the Hilbert Curve in a previous article, and today will talk about the Koch Curve.|

|We didn’t get a White Christmas in Seattle this year.Let’s do the next best thing, let’s generate fractal snowflakes!What is a fractal? A fractal is a self-similar shape.Fractals are never-ending infinitely complex shapes. If you zoom into a fractal, you get see a shape similar to that seen at a higher level (albeit it at smaller scale). It’s possible to continuously zoom into a fractal and experience the same behavior.Two of the most well-known fractal curves are Hilbert Curves and Koch Curves. I’ve written about the Hilbert Curve in a previous article, and today will talk about the Koch Curve.|

What is a fractal? A fractal is a self-similar shape.

Two of the most well-known fractal curves are Hilbert Curves and Koch Curves. I’ve written about the Hilbert Curve in a previous article, and today will talk about the Koch Curve.

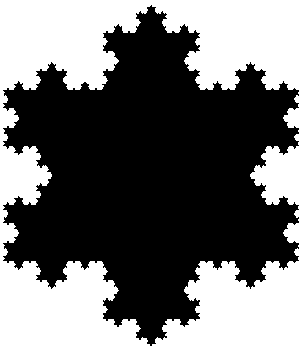

|The Koch curve is named after the Swedish mathematician Niels Fabian Helge von Koch (25 January 1870 – 11 March 1924).An example Koch Snowflake is shown on the right. |

|

An example Koch Snowflake is shown on the right.

|

Here is an animation showing the effect of zooming in to a Koch curve. |

Recursion

The typical way to generate fractals is with recursion. Because fractals are comprised of self-similar versions of themselves at smaller scales (which in-turn are, themselves, comprised of smaller versions of themselves …), we can start with our desired dimension and recurse down until the required depth (precision) is achieved.

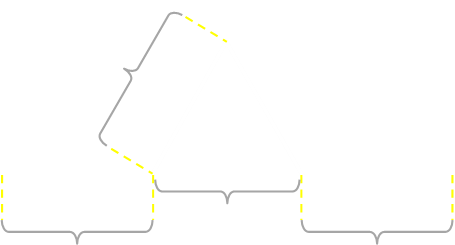

| |To generate a Koch curve we start off with a line of unit length.|

|

|To generate a Koch curve we start off with a line of unit length.|

| |Next we divide this line into three equal segments.|

|

|Next we divide this line into three equal segments.|

| |We then remove the center section and replace this with two sides of an equilateral triangle (the sides of which are the same length as the removed segment).We are now left with a shape comprised of four equal length segments.|

|We then remove the center section and replace this with two sides of an equilateral triangle (the sides of which are the same length as the removed segment).We are now left with a shape comprised of four equal length segments.|

We are now left with a shape comprised of four equal length segments.

Now, we can repeat the same exercise for each of these four smaller segments. If we imagine that each of these four line segments are, themselves, made up from smaller versions of themselves, the curve starts to form …

Snowflake

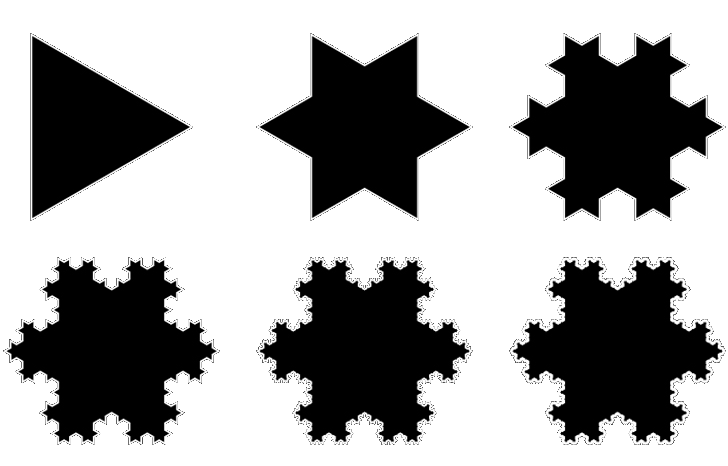

To make a snowflake, instead of starting with just one line, we start with three similar lines, arranged as an equilateral triangle, and apply the process in parallel to each of three segments.

Above are the first few iterations of a Koch snowflake. Even though we know the length of the all the line segments is increasing with each step, it’s looking like the area is not getting that much bigger with successive terms? Does the area asymptote to a certain value? If so, what is this value? How do we go about calculating the area at every depth?

(It’s clear that the area can’t grow ubounded forever; The shape is bounded by a hexagon-like shape. No matter how far down we recurse, the shape will never grow outside this hexagon, so it can’t keep growing forever!)

Time for a little math …

Length of curve

Let’s start with the easy part. What is the total length of the edges of a Koch snowflake with every iteration?

If we assume that the length of each side of the starting triangle is one unit. Let’s consider what happens with each iteration (and we only need to consider one side; to get the total, we simply multiply by three).

Each time we step down, the length of each side is replaced by four lots of lengths that are one third the size of the previous length. Here is the simple equation for the length of the sides at each depth:

You can see as n increases, the length is unbounded.

Snowflake area

What about the area? This is a little more complicated to calculate.

First let’s consider what happens to the number of sides.

When we first start out, there are 3 sides to the triangle, each of length one unit.

On the next iteration, there are 12 sides, each of length 1/3 unit (Each of the three straight sides of triangle is replaced with four new segments). On the next iteration, there are 48 sides, each of length 1/9 unit (every one of the 12 previous edges replaced by four new segments) …

Each level deeper we go creates four times as many sides as the level before.

3, 12, 48, 192, 768, 3072 …

|

Next we need to calculate the area inside the triangles.The area of an equilateral triangle with side s is given by the equation to the left. |

The area of an equilateral triangle with side s is given by the equation to the left.

Let’s see what happens to the area on each step. Let’s keep with the notation that the length of the side of initial triangle is s.

| |The area of the first iteration is simply the area of the base triangle|

|The area of the first iteration is simply the area of the base triangle|

For the next iteration the area of the snowflake is increased by the three red triangles shown in the diagram below

For the next iteration we add an additional 12 smaller triangles. The area of each of these new triangles is added to the total area:

And so on …

Below is the equation showing how the area of the snowflake increases with each depth. It’s easy to see how each of the terms are formed; each new depth adds four times are many new triangles, each of length 1/3rd of the previous. In order to find the sum, it helps if we clean this up a little.

First we can pull out a commom √3s2/4 term:

Then we can pull out any additional 1/4 from the bracket (in order to multiply each term inside by four):

Using the following equality (flipping the exponents), we can move the square to the denominator and the increasing power to the numerator.

Now all the exponents are the same order and we can combine them and pull the 4 inside each of the terms. We’re getting close …

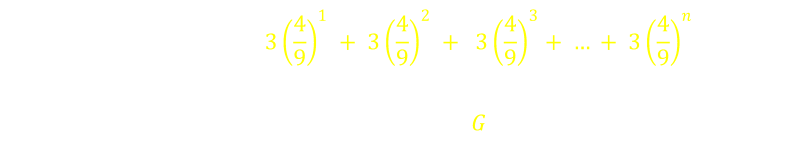

I’ll define the infinite series (shown in gold below) to be the letter G.

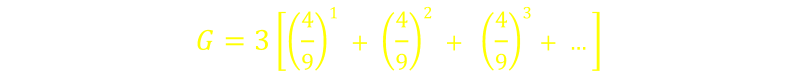

This is the expansion for G:

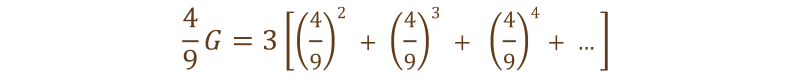

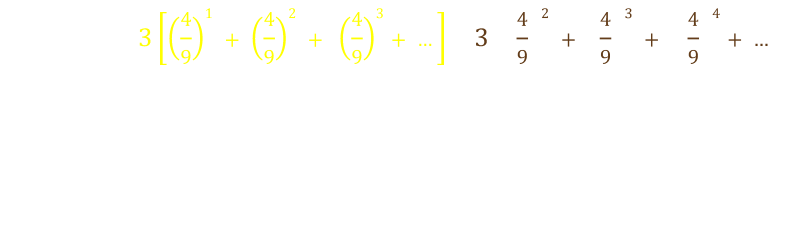

Here’s a clever trick. Now that we know G, we can work out 4/9ths of G too.

We can subtract the 4/9ths of G from G, and you can see that all the terms, except the first, of the infinite series cancel:

This gives an equation for 5/9ths of G which we were able to rearrange to find the total of the infinite series G.

Finally, now that we have a value for G, when can substitute this back into the original formula to give an equation for the infinite sum. This gives the value for the Area of the snowflake with an infinite depth. The value for area asymptotes to the value below.

If you look closely at the formulae you will see that the limit area of a Koch snowflake is exactly 8/5 of the area of the initial triangle.

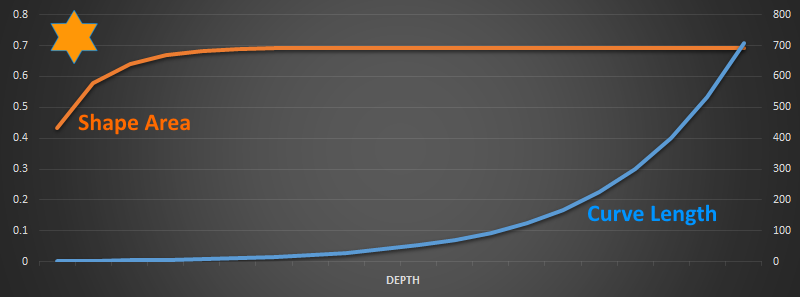

Graph

Below is a graph showing how the area of the snowflake changes with increasing fractal depth, and how the length of the curve increases. The snowflake area asymptotes pretty quickly, and the curve length increases unbounded. A Koch snowflake has a finite area, but an infinite perimeter!

Other interesting facts

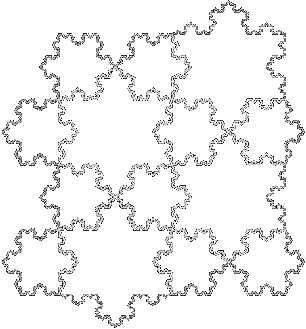

Koch snowflakes of different sizes can be tesellated to make interesting patterns:

Thue-Morse

| |Here’s an interesting relationship between Koch curves and Thue-Morse sequences.To first understand the relationship, we first need to understand a Thue-Morse sequence!The Thue–Morse sequence (or Prouhet–Thue–Morse sequence), is an infinite binary sequence obtained by starting with 0 and successively appending the Boolean complement of the sequence obtained thus far.

|Here’s an interesting relationship between Koch curves and Thue-Morse sequences.To first understand the relationship, we first need to understand a Thue-Morse sequence!The Thue–Morse sequence (or Prouhet–Thue–Morse sequence), is an infinite binary sequence obtained by starting with 0 and successively appending the Boolean complement of the sequence obtained thus far. - We start with 0.- The bitwise negation of 0 is 1.- Combining these, the first 2 elements are 01.- The bitwise negation of 01 is 10.- Combining these, the first 4 elements are 0110.- The bitwise negation of 0110 is 1001.- Combining these, the first 8 elements are 01101001.- And so on …|

- We start with 0.- The bitwise negation of 0 is 1.- Combining these, the first 2 elements are 01.- The bitwise negation of 01 is 10.- Combining these, the first 4 elements are 0110.- The bitwise negation of 0110 is 1001.- Combining these, the first 8 elements are 01101001.- And so on …|

To first understand the relationship, we first need to understand a Thue-Morse sequence!

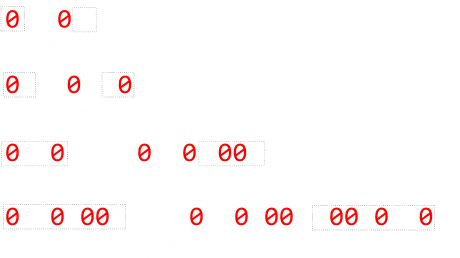

The first few terms are shown below:

-

T0 = 0

-

T1 = 01

-

T2 = 0110

-

T3 = 01101001

-

T4 = 0110100110010110

-

T5 = 01101001100101101001011001101001

-

T6 = 0110100110010110100101100110100110010110011010010110100110010110

|

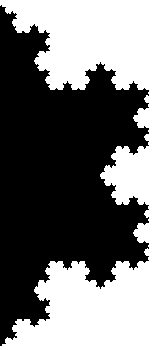

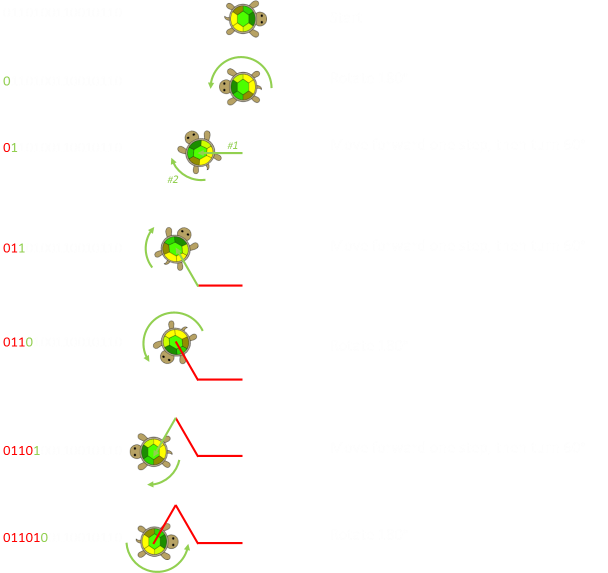

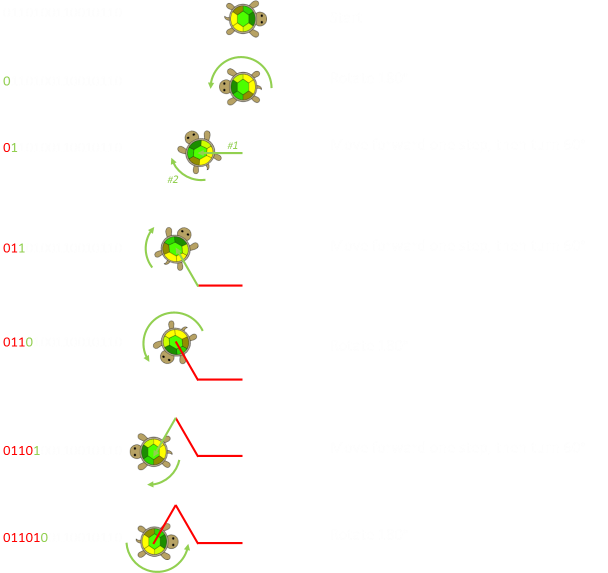

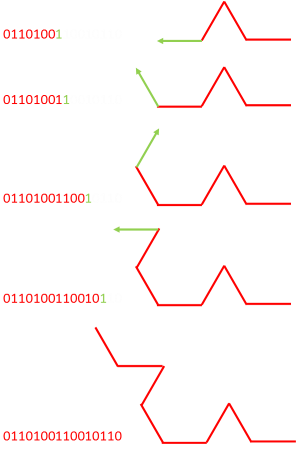

If you are familiar with the educational programming language Logo, and Turtle graphics, it’s possible to turn these sequences of binary digits into Koch curves. |

To do this, we simple apply the following rules: | 0 | If we encounter a zero, we turn 180°| | 1 | If we encounter a one, we step forward one space, then turn 60°|

That’s it! Lets apply these rules to T4 = 0110100110010110, and see what we get …

I think you can see where this is going. Let’s finish this off, but in the interests of space, I’ll not draw the turtle.

The Thue-Morse sequence T4 has given instructions to generate half of the Koch Curve.

If we would have used T5 = 01101001100101101001011001101001, the full curve would have been generated.

Odd numbered Thue-Morse generate half curves, and even numbered Thue-Morse numbers generate full curves.

You can find a complete list of all the articles here. Click here to receive email alerts on new articles.

Click here to receive email alerts on new articles.