If you spend time programming computers you are probably very familiar with number bases other than decimal.

|If you spend time programming computers you are probably very familiar with number bases other than decimal.The chances are good that you are very familiar with binary (base 2) and Boolean arithmetic. More manageably, you are probably pretty comfortable with hexadecimal too (base 16).Depending on the systems you work on, you might even have had some experience with octal (base 8).| |

|

Depending on the systems you work on, you might even have had some experience with octal (base 8).

11101000001012 = 164058 = 742910 = 1D0516

|

(The standard way to indicate a number base, if it is not obvious from the context, is with a subscript at the end, next to the least significant digit).Without even realizing it, you probably have a fair degree of familiarity with sexagesimal (base 60), as there are sixty seconds in a minute, and sixty minutes in an hour. If you’ve used decimal representations of time (or worked with angles, or lat/lng coordinates), you might have had to convert between them (Scientific calculators typically have built in functions to handle DMS conversions because they are so common). |

Without even realizing it, you probably have a fair degree of familiarity with sexagesimal (base 60), as there are sixty seconds in a minute, and sixty minutes in an hour. If you’ve used decimal representations of time (or worked with angles, or lat/lng coordinates), you might have had to convert between them (Scientific calculators typically have built in functions to handle DMS conversions because they are so common).

Half an hour (0.5hr) = 30 minutes

Interestingly there are echoes of other number bases still in circulation. Just because we have ten fingers (which is probably the root cause of the origins of decimal), society grew up with some other bases. Here are a few:

-

There are 16 ounces in one pound (of weight), and if I ask my dad his weight he will still reply in Stones (there are 14 Pounds in a Stone).

-

Pre-decimilasation, in the UK, there were 12 Pennies in one Shilling, and 20 Shillings in one Pound (meaning one Pound = 240 Pennies). I was born pre-decimilasation, and as I was going through school many of my old text books had problems about adding, subtracting, multiplying, and dividing various amounts of pounds-shillings-pence.

-

There are 24 hours in a day (or twelve repeated hours, depending on your perspective).

-

Many languages show a bias towards base 20 numbering systems (Irish, Gaulish …), and the Mayans also used a vigesimal system (base 20).

-

You buy doughnuts by the dozen, and beer by the case!

Positional Notation

| |Most number systems we use today can be described as positional notation (sometimes called place-value notation). The position a digit is in consistently determines its value. This greatly simplifies arithmetic. The most common example of non-positional notation are Roman Numerals. Here the same symbol can have different values depending on its position and is modified by the symbols around it. Chaos!|

|Most number systems we use today can be described as positional notation (sometimes called place-value notation). The position a digit is in consistently determines its value. This greatly simplifies arithmetic. The most common example of non-positional notation are Roman Numerals. Here the same symbol can have different values depending on its position and is modified by the symbols around it. Chaos!|

The most common example of non-positional notation are Roman Numerals. Here the same symbol can have different values depending on its position and is modified by the symbols around it. Chaos!

If you write down two Roman Numerals, one above the other, and try to add them using the same techniques you use for place-value arithmetic, you are going to have a very bad time!

Non-positional notation representations, however, are not all bad and chaotic. There are some incredible useful representation systems. Probably the most well known in Binary Gray Code.

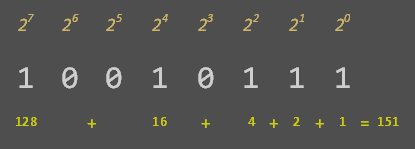

The standard for positional notation is that for each digit that you move to the left, you increase in power by one of the base that multiplies any digit in that column. In base 10, the first column is the measure of units 100, the next column the measure of tens 101, then hundreds 102, thousands 103 …

| |It’s the same principle for other bases, for instance binary, as shown on the left.Here is shown the decimal number 151 represented by the unique sum of various powers of two. This highlights why binary is so commonly used in digital computers; a value in a binary digit is either set, or not. Electrically, a voltage is either present (digitally) or not.|

|It’s the same principle for other bases, for instance binary, as shown on the left.Here is shown the decimal number 151 represented by the unique sum of various powers of two. This highlights why binary is so commonly used in digital computers; a value in a binary digit is either set, or not. Electrically, a voltage is either present (digitally) or not.|

Here is shown the decimal number 151 represented by the unique sum of various powers of two. This highlights why binary is so commonly used in digital computers; a value in a binary digit is either set, or not. Electrically, a voltage is either present (digitally) or not.

|Any number can be uniquely described by summing up the digits multiplied by their respective powers of the number base. Where b is the number base, and di is the ith digit in the number.| |

|

Where b is the number base, and di is the ith digit in the number.

Fractions

Fracational parts of a number can be represented by digits placed to the right of a ‘decimal point’, and these are used to represent progressively negative exponents of the base. In decimal: 1/10ths (10-1), 1/100ths (10-2), 1/1,000ths (10-3) …

e.g. 0.12510 = 1/10 + 2/100 + 5/1,000

There’s no reason why a number base (called a radix by mathematicians), needs to be an integer!

It’s possible, if you wanted to, to chose pretty weird number bases. Here are just a couple:

base π

|Even though π is irrational (in decimal), that’s not a problem. We can just apply the same principles of increasing powers of the base and represent numbers based on powers of π.… π3, π2, π1, π0A circle with diameter 1π will have a circumferance of 10π (and one with a diameter 10π will have a circumferance of 100π …)A circle with a radius of 1π will have an area of 10π, a circle with a radius of 10π will have an area of 1000π and a circle with a radius of 100π will have an area of 100000π …| |

|

… π3, π2, π1, π0

A circle with a radius of 1π will have an area of 10π, a circle with a radius of 10π will have an area of 1000π and a circle with a radius of 100π will have an area of 100000π …

base e

|A base using the transcendental constant e, has some interesting properties, one of which is that the natural logs behave a little like ‘common’ logarithms:ln(1e) = 0, ln(10e) = 1, ln(100e) = 2, ln(1000e) = 3| |

|

ln(1e) = 0, ln(10e) = 1, ln(100e) = 2, ln(1000e) = 3

base √2

|Ok, this is fascinating: base √2 has an interesting relationship with vanilla base 2 (binary).To convert any number from binary into base √2, all you need to do is insert a zero between every digit of the binary representation!191110 = 111011101112 = 101010001010100010101√2|

To convert any number from binary into base √2, all you need to do is insert a zero between every digit of the binary representation!

You can see from this that any integer can be represented in base √2 without the need of a ‘decimal point’, more strictly called a ‘radix point’.

base φ

|Ah, the Golden Ratio. It likes to pop up in lots of interesting places (some of them are even true).The Golden Ratio radix has been studied so much that it has a colloquial name of Phinary!Any non-negative real number can be represented as a base φ numeral using only the digits 0 and 1, and avoiding the digit sequence “11”. Below are the first ten decimal digits and their phinary equivalents:| |

|

The Golden Ratio radix has been studied so much that it has a colloquial name of Phinary!

|Decimal|Powers of φ|Base φ

|1|φ0|1|

|2|φ1 + φ−2|10.01|

|3|φ2 + φ−2|100.01|

|4|φ2 + φ0 + φ−2|101.01|

|5|φ3 + φ−1 + φ−4|1000.1001|

|6|φ3 + φ1 + φ−4|1010.0001|

|7|φ4 + φ−4|10000.0001|

|8|φ4 + φ0 + φ−4|10001.0001|

|9|φ4 + φ1 + φ−2 + φ−4|10010.0101|

|10|φ4 + φ2 + φ−2 + φ−4|10100.0101|

|Some of these weird bases might seem slightly arbitrary (and maybe fun if you are a mathematician), but do they have any ‘practical’ applications? Well yes, maybe they do.Base e, for instance, is very efficient at storing information. Something called radix economy measures the number of digits needed to express a number in that base, multiplied by the radix.(A binary representation of a number is ‘long’, but only uses one of two values. Conversely, storing something in decimal might make a number ‘shorter’, but each symbol could be pulled from a larger number of values. A number stored in base e is the most mathematically efficient way to encode it, according to information storage theory*). This is one of those ‘Goldilocks’ type issues. Make a radix too small (like binary), and whilst your ‘dictionary’ of symbols to use is very small, the resulting string representing the number is very long. Conversely, having a large radix would shorten the length of the string needed to represent the number, but each digit would need need to come from a large dictionary, and this would take more space to encode each digit.| |

|

Base e, for instance, is very efficient at storing information. Something called radix economy measures the number of digits needed to express a number in that base, multiplied by the radix.

This is one of those ‘Goldilocks’ type issues. Make a radix too small (like binary), and whilst your ‘dictionary’ of symbols to use is very small, the resulting string representing the number is very long. Conversely, having a large radix would shorten the length of the string needed to represent the number, but each digit would need need to come from a large dictionary, and this would take more space to encode each digit.

“This one is too big”, “This one is too small” … which radix is “Just right”? …

… the answer is base e.

| Another analogy is written language. Using the Western (Latin) alphabet, we can write words, but the average length of words is many characters each. Compare this to written Chinese where there are many thousands of symbols, and many words require just one symbol. |  |

Outside of the analog world, digital computers store precise quantized values for representations. If computer circuits were manufactured to store data *tri-state instead of binary, (3 is a nearer integer to e than 2), then computers could store data more efficiently.

| |e 2.7182818284590452353602874713526624977572470936999595 …We’re getting a little off-topic here, but the same math applies to things like menu systems and telephone menu systems. If these services offered ternary trees (tri-state) menus, they would minimize the average number of menu choices the average customer would need to listen to to get to their desired location.|

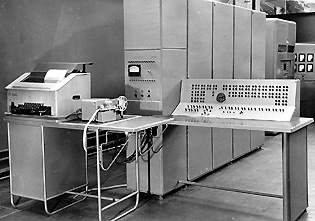

|In the early days of computing, a few experimental Soviet computers were built that processed using balanced ternary (more on this later) instead of binary, the most famous being the Setun (image on right), which is named after a river in Moscow. Over fifty of these computers were built in the 1960s and 1970s.I love decscriptions of these devices from one of the developers, when comparing the binary computer which stores values in one of two states “flip-flop”, to that of ternary, they used the words “flip-flap-flop”.By using balanced ternary + , 0 , – to store values (a “trit”, instead of a a “bit”)*, as we will see below, this has interesting benefits for encoding the sign of the number too.|

|e 2.7182818284590452353602874713526624977572470936999595 …We’re getting a little off-topic here, but the same math applies to things like menu systems and telephone menu systems. If these services offered ternary trees (tri-state) menus, they would minimize the average number of menu choices the average customer would need to listen to to get to their desired location.|

|In the early days of computing, a few experimental Soviet computers were built that processed using balanced ternary (more on this later) instead of binary, the most famous being the Setun (image on right), which is named after a river in Moscow. Over fifty of these computers were built in the 1960s and 1970s.I love decscriptions of these devices from one of the developers, when comparing the binary computer which stores values in one of two states “flip-flop”, to that of ternary, they used the words “flip-flap-flop”.By using balanced ternary + , 0 , – to store values (a “trit”, instead of a a “bit”)*, as we will see below, this has interesting benefits for encoding the sign of the number too.| |

|

I love decscriptions of these devices from one of the developers, when comparing the binary computer which stores values in one of two states “flip-flop”, to that of ternary, they used the words “flip-flap-flop”.

| |Note - There is a subtle difference between balanced ternary, which uses values: −1, 0, +1 cf. vanilla ternary, which uses values: 0, 1 ,2. More details about this a little later, below …|

|Note - There is a subtle difference between balanced ternary, which uses values: −1, 0, +1 cf. vanilla ternary, which uses values: 0, 1 ,2. More details about this a little later, below …|

*A collection of “trits” form together to make a “tryte”, just like “bits” make a “byte”!

Further down the Rabbit Hole (negative radices)

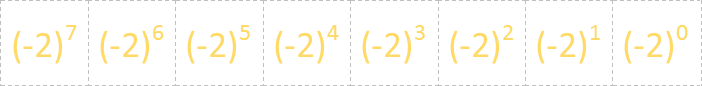

OK, let’s go further down the rabbit hole. How about, instead of using fractional bases, we use negative bases? Mathematically, again, this is easy to do. Odd powers of negative bases create negative numbers, but even powers produce positive ones. Because we add these digits up it is still possible to create distinct numbers. For example, let’s take a look at base -2. Sometimes called “Negabinary”.

111011001-2

= 1×(-2)8 + 1×(-2)7 + 1×(-2)6 + 0×(-2)5 + 1×(-2)4 + 1×(-2)3 + 0×(-2)3 + 0×(-2)1 + 1×(-2)0

= 1×(256) + 1×(-128) + 1×(64) + 0×(-32) + 1×(16) + 1×(-8) + 0×(4) + 0×(-2) + 1×(1)

= 256 − 128 + 64 + 16 − 8 + 1

= 20110

| |There is a very interesting property of negative radix encoding: There is no distinction between positive and negative numbers; they are all just numbers, and all encoded the same way. The sign of the number is encapsulated in the number. We don’t need a sign bit.|

|There is a very interesting property of negative radix encoding: There is no distinction between positive and negative numbers; they are all just numbers, and all encoded the same way. The sign of the number is encapsulated in the number. We don’t need a sign bit.|

If all you’ve ever used is unsigned integers, you might not see this as much of an advantage, but for everyone else, signed numbers are typically coded using a two’s complement (sort of like how an odometer on a car wraps around the clock after getting to 99999), and negative numbers are represented backwards (from over the top) and are identifiable by having the topmost bit (most signficant bit) set.

Again this is fine if you are dealing with numbers that are encoded in just one byte/word (depending on the width you are dealing with), but if you need to encode and deal with arithmetic for larger numbers, you need to span these numbers across multiple words. Now the words are different. The ‘lower’ words of the number use all bits, but the most significant word has the top bit reserverd to (potentially) indicate that the number is negative.

Let’s take a look a negadecimal:

We can apply the same negative radix strategy to describe numbers in base -10 (called ‘negadecimal’)

17478-10

= 1×(-10)4 + 7×(-10)3 + 4×(-10)2 + 7×(-10)1 + 8×(-10)0

= 1×(10000) - 7×(1000) + 4×(100) - 7×(10) + 8×(1)

= 10000 − 7000 + 400 − 70 + 8

= 333810

Just like negabinary, numbers encoded in negadecimal do not need explicit sign indicators; this is encapsulated into the number system, and all can be treated exactly the same way.

Tables of numbers

Here are representations of a selection of numbers in decimal, negadecimal, negabinary and negaternary: |-100|1900|11101100|121112| |-64|76|11000000|120212| |-32|48|100000|1021| |-16|24|110000|1102| |-15|25|110001|1220| |-14|26|110110|1221| |-13|27|110111|1222| |-12|28|110100|1210| |-11|29|110101|1211| |-10|10|1010|1212| |-9|11|1011|1200| |-8|12|1000|1201| |-7|13|1001|1202| |-6|14|1110|20| |-5|15|1111|21| |-4|16|1100|22| |-3|17|1101|10| |-2|18|10|11| |-1|19|11|12| |0|0|0|0| |1|1|1|1| |2|2|110|2| |3|3|111|120| |4|4|100|121| |5|5|101|122| |6|6|11010|110| |7|7|11011|111| |8|8|11000|112| |9|9|11001|100| |10|190|11110|101| |11|191|11111|102| |12|192|11100|220| |13|193|11101|221| |14|194|10010|222| |15|195|10011|210| |16|196|10000|211| |32|172|1100000|12122| |64|144|1000000|11101| |100|100|110100100|10201| |1000|19000|10000111000|2212001| |10000|10000|111101100010000|222112101|

You will notice for the nega representations, the negative numbers all have an even number of digits, and positive numbers all have an odd number of digits.

Adding two nega numbers

Now that we have have two negadecimal numbers, how do we add them together?

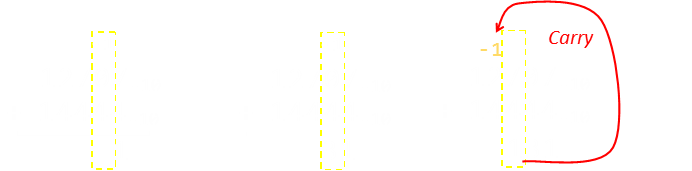

It’s actually not as as hard as you might think, because negadecimal is still a positional notational system. We simply apply the addition rules we learned in school; summing columns (from least significant to most significant, carrying forward as required).

First, a trivial example, adding two ‘small’ numbers (no carry). What is the sum of 12343-10 and 6101-10?

12343-10 = 826310 and 6101-10 = −589910

Notice here how the two numbers are treated the same, even though it turns out that one of them happens to be negative?

It behaves just as we’d expect, we just sum up each column. The sum for the first digit is 1+3=4. So far so good, and we can walk over the columns in order. The result is 18444-10, which correspends to 236410, which is what we expect (=826310−589910).

OK, now let’s introduce a more complicated example. How do we deal if we have an overflow (carry) on any column? The answer, like traditional arithmetic, is we carry over to the next column, but, because we are dealing with negadecimal, we carry over a negative one.

Adding the 4 and the 7 together, we obtain 11. We write down 1 in the total, and carry a −1 to the top of the next column over and then carry on. Next we find that −1+4=3, so no carry this time …

We carry this process until we reach the end (which is again, thankfully is what we expect!) Each time, we carry forward as needed.

12707-10 + 14444-10 = 25131-10

870710 + 636410 = 1507110

We need to learn one last trick, and then we are home and dry. What do we do if we need to carry forward a negative one, and all we in the next column are zeros? (we can’t have a -1, as each digit needs to be in the range 0-9). The answer is pretty simple, as -1 in negadecimal is 19, we just add this to the front (it’s like saying we ‘borrow’ 1 from the next digit over and then use this to help mop-up the carry that propogated forward). To ‘borrow’ a one, we subtract off negative one, which is the same as carrying forward a positive one.

The same borrow principle applies at the ‘front’ of the number (most significant digit), if needed, until we have no more carries to propogate forward.

Interestingly, in this example the negadecimal and decimal representation of the two numbers to be added are the same.

10009-10 + 90002-10 = 1900191-10 1000910 + 9000210 = 10001110

We can apply the same strategy for adding negabinary numbers; applying the principles we learned at school and carrying forward as appropriate. We need to take a little more care with negabinary as, even when adding two numbers, we might need to carry forward two colums at single time!

Balanced Ternary

A further mention should be made of balanced ternary, since we made reference to it earlier concerning the early Soviet era computers. Traditional ternary uses the values: 0,1,2 to encode by using them to multiply the powers of the base. Balanced ternary uses the digits: −1, 0, +1.

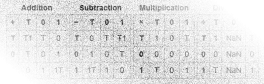

| |There is a subtle difference from a negative radix representation (negaternary) and balanced ternary because, with balanced ternary, we are still using a positive radix, but each digit can elect to use it, have none of it, or subtract it! It’s sort of like pivoting it the other way. Balanced ternary, by allowing encoding of positive and negative numbers, also has the same advantage of treating all numbers the same (no sign bits needed), but has some additional advantages including that the truth tables for digit additional, subtraction, mulitplication, and division are simpler.Because any digit can be in one of three states, and it would be (very, very) confusing to propose that “2” represent “−1”, a different convention is used.|

|There is a subtle difference from a negative radix representation (negaternary) and balanced ternary because, with balanced ternary, we are still using a positive radix, but each digit can elect to use it, have none of it, or subtract it! It’s sort of like pivoting it the other way. Balanced ternary, by allowing encoding of positive and negative numbers, also has the same advantage of treating all numbers the same (no sign bits needed), but has some additional advantages including that the truth tables for digit additional, subtraction, mulitplication, and division are simpler.Because any digit can be in one of three states, and it would be (very, very) confusing to propose that “2” represent “−1”, a different convention is used.|

Because any digit can be in one of three states, and it would be (very, very) confusing to propose that “2” represent “−1”, a different convention is used.

In old Russian literature, documentation sometimes used an inverted digit “1” to represent “−1”, but this is hard to read and easily confussed. Other researchers have used “T” to represent “−1”, and others, still have used “Θ”. I’m going to use “T” below.

… + d232 + d131 + d030 where dn is {−1, 0, +1}

Examples:

1T0bal3 = 1×32 − 1×31 + 0×30 = 9 − 3 + 0 = 610

TT1bal3 = −1×32 − 1×31 + 1×30 = −9 − 3 + 1 = −1110

101bal3 = 1×32 + 0×31 + 1×30 = 9 + 0 + 1 = 1010

1T10bal3 = 1×33 − 1×32 + 1×31 + 0×30 = 27 − 9 + 3 + 0 = 2110

Balanced ternary is pretty awesome!

Deeper still down the Rabbit Hole - Mixed Radix Systems

There is no reason why moving to the left in positional notation should necesserily increase the exponent of the base. This is just a common definition and a standard we agree on. Provided you describe the rules and consistently apply them, you can encode numbers however you feel like. For instance you could use the columns to represent factorials (or better still primorials, which are like factorials but each next term you multiply by is not the next number in the sequence, but the next occuring prime; Primorials are all square-free integers, and each one has more distinct prime factors than any number smaller than it).

In a mixed radix system, the maximum value allowed in any digit position is variable. ||Factorial BaseDigit|d7|d6|d5|d4|d3|d2|d1|d0| |Place value|7!|6!|5!|4!|3!|2!|1!|0!| |Decimal|5040|720|120|24|6|2|1|1|

| Primorial Base | —— | ||||||

| Digit | d6 | d5 | d4 | d3 | d2 | d1 | d0 |

| Radix | 17 | 13 | 11 | 7 | 5 | 3 | 2 |

| Place value | (p6=13) | (p5=11) | (p4=7) | (p3=5) | (p2=3) | (p1=2) | (p0=1) |

| Decimal | 30030 | 2310 | 210 | 30 | 6 | 2 | 1 |

24201! = 34910

= (2 × 5!) + (4 × 4!) + (2 × 3!) + (0 × 2!) + (1 × 1!)

If mixed radix math sounds crazy, remember back to the some of the opening comments in this article. We live in a mixed radix society. There are 60 seconds in a minutes, and 60 minutes in an hour, but 24 hours in a day, and (almost) 365.25 days in a year …

Last stop on the crazy train - complex radices

|I’m not going to talk about them here, but there’s no reason to restrict yourself to real numbers when selecting a number base! Why not use a complex radix?Three well researched bases are base 2i (known as Quatar imaginary base), base −1+i, and base −i−1. The quater-imaginary numeral system was first proposed by Donald Knuth in 1955, in a submission to a high-school science talent search!| |

|

Three well researched bases are base 2i (known as Quatar imaginary base), base −1+i, and base −i−1. The quater-imaginary numeral system was first proposed by Donald Knuth in 1955, in a submission to a high-school science talent search!

As we’ve seen, a consequence of using negative bases to encode numbers is that there is no distinction between a positive and negative number representation (no sign bit is needed compared to traditional binary encoding). Not only does this greatly simplify data types, but it also reduces (by half) things like conditional instructions and even basic operations that no longer have to worry about the sign bit; if it is present, and how to deal with it. Truncation is easier (it corresponds to rounding), and math operations can be applied agnostic of the length of words (and the position of the current word relative to the entire number). The number of instructions required is also reduced.

Compilers would be simpler to write, and once written, easier to test, and there would be less paths executed.

| |Also, as we have seen from information theory, a base closer to e is a more efficient way to store information. Combining the benefits of non-positive bases and non-binary bases in balanced ternary produces, as the Soviets experimented with, a pretty elegant foundation for an efficient and neat computing platform. Shouldn’t this be the platform we aspire to?|

|Also, as we have seen from information theory, a base closer to e is a more efficient way to store information. Combining the benefits of non-positive bases and non-binary bases in balanced ternary produces, as the Soviets experimented with, a pretty elegant foundation for an efficient and neat computing platform. Shouldn’t this be the platform we aspire to?|

If history were to repeat itself, would we still end up in a binary based computing society? If the earlier pioneers had continued with tri-state research, would our devices now all be using trits and trytes?

If we meet aliens, will they be using base three devices? (mathematics, after all, is a universal language and the benefits of balanced ternary are agnostic as to how to describe them).

Clearly there is physical simplicity in having a binary system (which is why we initially went down this path, and have continued down it to date): Something is there, or it is not. A voltage is present or it is not. Magnetic flux is there or not. A hole is present in a piece of punched-tape or not. But with the technology available today we could probably come up with solutions to reliably store and manipulate tri-state data. These days, data is typically not stored as physical two-state presence (or lack of) of something; it is usually in some electronic form. Is it time to ditch binary and switch to balanced ternary?

| |Insert joke here about “hanging chads”|

|Insert joke here about “hanging chads”|

Will modern digital computers ever move away from binary? …

You can find a complete list of all the articles here. Click here to receive email alerts on new articles.

Click here to receive email alerts on new articles.