I just returned from NIPS 2015, a joyful week of corporate parties featuring deep learning themed cocktails, money talk, recruiting events, and some scientific activities on the side. In the latter category, I co-organized a workshop on adaptive data analysis with Vitaly Feldman, Aaron Roth and Adam Smith.

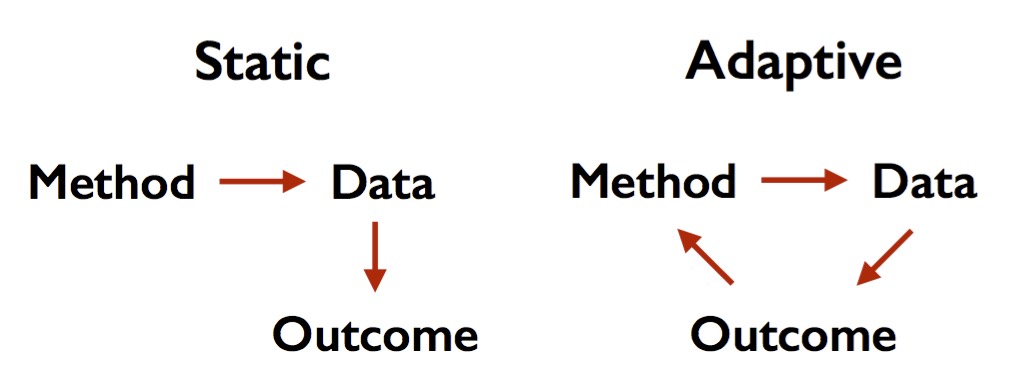

Our workshop responds to an increasingly pressing issue in machine learning and statistics. The classic view of these fields has it that we choose our method independently of the data to which we intend to apply the method. For example, a hypothesis test must be fixed in advance before we see the data. I sometimes call this static or confirmatory data analysis. You need to know exactly what you want to do before you collect the data and run your experiment. In contrast, in practice we typically choose our methods as a function of the data to which we apply them. In other words, we adapt our method to the data.

Adaptivity is both powerful and dangerous. Working adaptively gives us greater flexibility to make unanticipated discoveries as it allows us to execute more complex analysis work flows. But it can also lead to false discovery and misleading conclusions far more easily than static data analysis. While there are many other issues to keep in mind, is not unreasonable to blame our lack of understanding adaptivity in part for exacerbating a range of problems from false discovery in the empirical sciences to overfitting in machine learning competitions.

I was hugely impressed with the incredibly exciting group of participants and audiences from both computer science and statistics that our workshop brought together. I felt that we made actual progress on beginning to understand the diverse perspectives on this complex issue. The goal of this post is to convey my excitement for this emerging research area as I attempt to summarize the different perspectives we saw.

The frequentist statistics perspective

Null hypothesis tests are still widely used across the empirical sciences to gauge the validity of findings. Scientists routinely calculate p-values with the hope of being able to reject a null hypothesis and thus claim a “statistically significant” finding. If we carry out multiple hypothesis tests, we need to adjust our p-values for the fact that we made multiple tests. A safe way of correcting for multiple tests is the Bonferroni correction which amounts to multiplying all p-values by the number of tests. Computer scientists call this the union bound. While Bonferroni is safe, it makes discoveries difficult in the common situation where we have lots of tests and no individual signal is particularly strong. A more powerful alternative to Bonferroni is to control the False Discovery Rate (FDR) proposed in a celebrated paper by Benjamini and Hochberg. Intuitively, controlling FDR amounts to putting a bound on the expected ratio of all false discoveries (number of rejected true null hypotheses) to all discoveries (number of rejected nulls). The famous Benjamini-Hochberg procedure gives one beautiful way of doing this.

Online False Discovery Rate

Andrea Montanari and Dean Foster discussed more recent works on online variants of FDR. Here, the goal is to control FDR not at the end of the testing process, but rather at all points along the way. In particular, the scientist must choose whether or not to reject a hypothesis at any time point without knowing the outcome of future tests. The word online should not be confused with adaptive. Although we could in principle choose hypotheses adaptively in this framework, we still need the traditional assumptions that all p-values are independent of each other and distributed the way they should be (i.e., uniform if the null hypothesis is true). If the selection of hypothesis tests was truly adaptive, these assumptions are unlikely to be satisfied and hard to be verified at any rate.

Inference after selection

But what if our hypothesis tests are chosen as a function of the data? For example, what if we first choose a set of promising data attributes and test only these attributes for significance? This natural two-step procedure is called inference after selection in statistics. Rob Tibshirani gave an entire keynote about this topic. Will Fithian went into further detail in his talk at our workshop. Several recent works in this area show how we can first perform variable selection using an algorithm such as Lasso, followed by hypothesis testing on the selected variables. What makes these results possible is a careful analysis of the distribution of the p-values conditional on the selection by Lasso. For example, if the test statistic followed a normal distribution before selection, it will follow a certain truncated normal distribution after selection. This approach leads to very accurate characterizations and often tight confidence intervals. However, it has the shortcoming that the we need to commit to a particular selection and inference procedure as the analysis crucially exploits these.

Rina Foygel Barber expanded on the theme of adaptivity and false discovery rate by showing how to control FDR when we first order our hypothesis tests in a data-dependent manner to allow for making important discoveries sooner.

The Bayesian view

Andrew Gelman’s talk (see his slides) contributed many illustrative examples of flawed empirical studies. His suggested cure for the woes of adaptivity was to do more of it. However, he advocated Bayesian hierarchical modeling to explicitly account for all the possible outcomes of an adaptive study. When asked if this wouldn’t put too much burden on the side of modeling, he replied that modeling should be seen as a feature as it forces people to explicitly discuss the experimental setup.

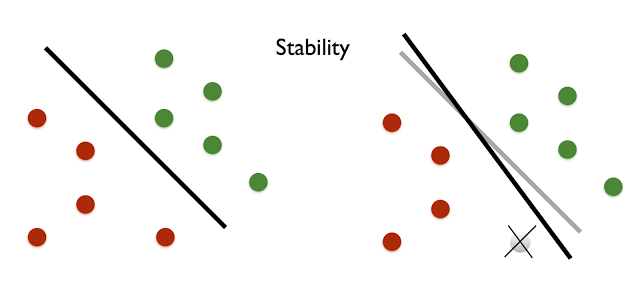

The stability approach

An intriguing approach to generalization in machine learning is the idea of stability. An algorithm is stable if its output changes only slightly (in some formal sense) under an arbitrary substitution of a single input data point. A seminal work of Bousquet and Elisseeff showed that stability implies generalization. That is, patterns observed by a stable algorithm on a sample must also exist in the underlying population from which the sample was drawn. Nati Srebro explained in his talk how stability is a universal property in the sense that it is both sufficient and necessary for learnability.

The issue is that stability by itself doesn’t address adaptivity. Indeed, the classic works on stability apply to the typical non-adaptive setting of learning where the sample is independent of the learning algorithm.

Cynthia Dwork talked about recent works that address this shortcoming. Specifically, differential privacy is a stability notion that applies even in the setting of adaptive data analysis. Hence, differential privacy implies validity in adaptive data analysis. Drawing on many powerful adaptive data analysis algorithms from differential privacy, this gives a range of statistically valid tools for adaptive data analysis. See, for example, my blog post on the reusable holdout method that came out of this line of work.

Information-theoretic measures

The intuition behind differential privacy is that if an analysis does not reveal too much about the specifics of a data set, then it is impossible to overfit to the data set based on the available information. This suggests an information-theoretic approach that quantifies the mutual information between the sample and the output of the algorithm. A recent work shows that indeed certain strengthenings of mutual information prevent overfitting. Being completely general, this viewpoint allows us, for example, to discuss deterministic algorithms, whereas all differentially private algorithms are randomized. James Zou discussed the information-theoretic approach further and mentioned his recent work on this topic.

Complexity-theoretic obstructions

In a dramatic turn of events, Jon Ullman told us why preventing false discovery in adaptive data analysis can be computationally intractable.

To understand the result, think of adaptive data analysis for a moment as an interactive protocol between the data analyst and the algorithm. The algorithm has access to a sample of size (n) and the analyst wants to learn about the underlying population by asking the algorithm a sequence of adaptively chosen questions.

What Jon talked about is that there is a computationally efficient adaptive data analyst that can force any computationally efficient algorithm on a sample of size (n) to return a completely invalid estimate after no more than (n^2) adaptively chosen questions. Non-adaptively, this would require exponentially many questions. While this is a worst-case hardness result, it points to a computational barrier for what might have looked like a purely statistical problem. The (n^2) bound turns out to be tight in light of the differential privacy based positive results I mentioned earlier.

Panel discussion

Toward the end of our workshop, we had a fantastic panel discussion on open problems and conceptual questions. I don’t remember all of it, unfortunately. Below are some topics that got stuck in my mind. If you remember more, please leave a comment.

Exact modeling versus worst-case assumptions

The approaches we saw cluster around two extremes. One is the case of exact analysis or modeling, for example, in the work on inference after selection. In these cases, we are able to exactly analyze the conditional distributions arising as a result of adaptivity and adjust our methods accordingly. The work on differential privacy in contrast makes no assumptions on the analyst. Both approaches have advantages and disadvantages. One is more exact and quantitatively less wasteful, but applies only to specific procedures. The other is more general and less restrictive to the analyst, but this generality also leads to hardness results. A goal for future work is to find middle ground.

Human adaptivity versus algorithmic adaptivity

There is a curious distinction we need to draw. Algorithms can be adaptive. Gradient descent, for example, is adaptive because it probes the data at a sequence of adaptively chosen points. Lasso followed by inference is another example of a single algorithm that exhibits some adaptive behavior. However, adaptivity also arises through the way humans work adaptively with the data. It even arises when a group of researchers study the same data set through a sequence of publications. Each publication builds on previous insights and is hence adaptive. It is much harder to analyze human adaptivity than algorithmic adaptivity. How can we even quantify the extent to which this is a problem? Take MNIST, for example. For almost two decades this data set has been used as a benchmark with the same test set. Although no individual algorithm is directly trained against the test set, it is quite likely that the sequence of proposed algorithms over the years strongly overfits to the test data. It seems that this is an issue we should take more seriously.

Building better intuition in practice

Any practical application of the algorithms we discussed will likely violate either the modeling assumptions we make or the quantitative regime to which our theory applies. This shouldn’t be surprising. Even in non-adaptive data analysis we make assumptions (such as normal approximations) that are not completely true in practice. What is different is that we have far less intuition for what works in practice in the adaptive setting.

What’s next?

After this workshop, I’m even more convinced that adaptive data analysis is here to stay. I expect lots of work in this area with many new theoretical insights. I also hope that these developments will lead to new tools that make the practice of machine learning and statistics more reliable.