A few weeks ago, Google announced that it was open sourcing an internal system called TensorFlow that allows one to build neural networks, as well as other types of machine learning models. (Disclaimer: I work for Google.) Because TensorFlow is designed to be more general than just a neural network framework, it takes a fairly abstract perspective compared to the way we usually talk about neural networks. But (not coincidentally) this perspective is very close to what I described in my last post, with rows of neurons defining output vectors and the connections between these rows defining matrices of weights. In today’s post, I want to describe the TensorFlow perspective, explain how it matches up with the traditional way of thinking about neural networks, and explain how TensorFlow generalizes the vector and matrix approach to include more general structures called tensors.

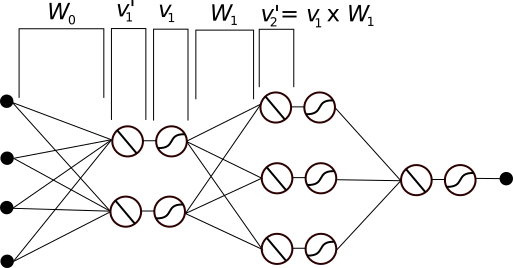

Recall that the standard view of an artificial neural network is a directed graph of neurons, where each neuron calculates a weighted sum of inputs from other neurons, then applies a non-linear function to determine its own output. Many neural networks have neurons arranged into rows or layers, with the neurons from one layer connected to the neurons in the next layer according to some pattern.

In my last post, I pointed out that you can think of each neuron as actually being two neurons – a linear neuron that calculates the weighted sum, which it sends to a non-linear neuron that applies the non-linear function to the output from the linear neuron. From this perspective, the linear neurons in each layer collect the output from the previous layer, and the non-linear neurons send their outputs to the next layer. As I described last time, you can then think of the output from each layer as a vector with one dimension/feature for each neuron. The connections between successive layers define a matrix such that the outputs of the linear neurons in one layer define a vector that’s equal to the outputs from the non-linear neurons of the previous layer multiplied by this matrix.

For a basic feed-forward network, we just have a sequence of layers, one after the other, as in the Figure below. I’ve indicated which parts of the Figure correspond to these vectors and matrices, and it’s possible to translate the diagram into the equations that describe how these all relate to each other. But the translation can be a bit tricky, and for more complex networks such as convolutional networks and RNNs, it becomes even harder to understand how the network functions from this perspective.

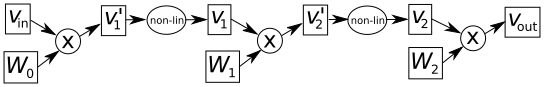

TensorFlow improves on this by dropping the biological analogy in favor of a graph that directly encodes the mathematical relationships between the elements. A TensorFlow graph for the neural network in the above Figure is shown in the Figure below. Instead of individual neurons, the elements of this graph are vectors, matrices and operations, with edges indicating how the operations are applied. (The v’s are vectors, W’s are matrices, and circles/ellipses are operators.) To figure out how each element is calculated, you simply follow the arrows backwards.

You can create a graph like this in TensorFlow by writing a script in Python. This graph includes operators for matrix multiplication and a non-linear operator (such as the sigmoid or the ReLu), but TensorFlow has a number of other operators as well, such as convolutional multiplication and pooling. Plus, since TensorFlow is open source, anyone can write their own operators. There are a number of tutorials on the official site where you can find details and examples.

Once you have this graph, you can ask TensorFlow to evaluate it for a given collection of inputs, but the more interesting part is, of course, the training. In other words, we want to select the values in the weight matrices by incrementally adjusting them via back propagation. This involves evaluating data points (following the graph forward), then determining the error and pushing it back to the weight matrices by calculating gradients. TensorFlow is able do this automatically because each of the operators is required to provide a pre-calculated gradient function. TensorFlow combines these using the chain rule, so if you tell it which of the vectors and matrices you want it to update, it can run back propagation automatically.

So that should give you an idea of how TensorFlow allows you to define neural networks, and other types of models, in terms of graphs of vectors, matrices and operators. But often it’s useful to create a neural network where each layer of neurons isn’t a just single row. For example, if you’re working with images, then the input layer would be more naturally described as a rectangular grid of values. Of course, this rectangle could be encoded as a vector, but it’s more natural to think of it as a matrix, particularly for something like a convolutional net, where the sliding windows are defined in terms of a rectangle. In fact, if it’s a RGB image then you really want to think of the input as three parallel rectangles, forming a rectangular box of values.

Now, I’m about to start using the term “dimension” in a way that’s a bit different than usual, so I want to be especially careful. Recall that a vector is defined by a list of numbers of some specified length. The set of all possible vectors of a given length define a vector space whose dimension is the length that we chose. But we’re going to say that every vector, no matter its length, is a one-dimensional tensor. So a one-dimensional tensor can define a vector space of any dimension you want. The one-dimensional part refers to the fact that we write the values of the vector along a one-dimensional line.

A matrix, on the other hand, is a grid of numbers with a certain number of rows and a certain number of columns. The set of all matrices of a given size also defines a vector space, whose dimension is the number of rows times the number of columns. But we’ll still say that a matrix is a two-dimensional tensor. (One dimension is rows. The other is columns.) So, as promised, we have two different meanings of the word “dimension” – one for the dimension of the space defined a vector or a matrix, one for the way in which the values are arranged when they’re written down.

Similarly, the rectangular box of values defined by the three rectangular layers of our RGB image defines a three-dimensional tensor, since we think of the values as being arranged into a three-dimensional shape. The space of all possible images defines a vector space whose dimension is much larger (three times the number of pixels to be precise), but it’s still a three-dimensional tensor.

To be even more precise about this, each of the features that make up a vector can be specified by a single index i. Each “feature” in a matrix is specified by two indices, i *and j. Each feature in the rectangular box for the RGB image is specified by three coordinates i, j, k. These are one-, two- and three-dimensional tensors, respectively. But there’s no reason to stop there. For example, if we want to keep track of the connections/weights between two layers we’ll need to index them by the both indices for the layer where they start and the indices for the layer where they end. For example, the weight from neuron i, j, k* of one layer to neuron x, y, z of the next layer is defined by the indices i, j, k, x, y, z. This is a six-dimensional tensor.

TensorFlow is designed to handle tensors of any dimension, and the operators that can be used to combine them. This, combined with the abstract and general nature of its approach to defining computation graphs makes it an extremely powerful and flexible platform for building machine learning models.

Like this:

Like Loading…

Related