So far on this blog, we’ve mostly looked at data in two forms – vectors in which each data point is defined by a fixed set of features, and graphs in which each data point is defined by its connections to other data points. For other forms of data, notably sequences such as text and sound, I described a few ways of transforming these into vectors, such as bag-of-words and n-grams. However, it turns out there are also ways to build machine learning models that use sequential data directly. In this post, I want to describe one such approach, called a recurrent neural network.

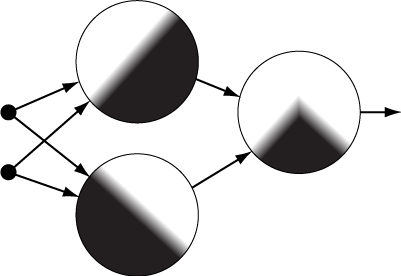

Recall that a standard (artificial) neural network, is defined by a graph of neurons (the big circles on the right), each of which takes either the features of a given data point (the small circles), or the outputs from other neurons, and calculates its own output from these values. In this way, each neuron defines a probability distribution on the space of possible input vectors. The density function of the distribution (shown inside each circle) is defined by the value that the neuron would output for any given input vector.

Recall that a standard (artificial) neural network, is defined by a graph of neurons (the big circles on the right), each of which takes either the features of a given data point (the small circles), or the outputs from other neurons, and calculates its own output from these values. In this way, each neuron defines a probability distribution on the space of possible input vectors. The density function of the distribution (shown inside each circle) is defined by the value that the neuron would output for any given input vector.

We can think of each probability distribution, and thus each neuron, as defining a “concept” such that its output for a given input vector defines the probability that the input vector represents the concept. In the figure, the high-probability regions are shown in white. The neurons that are connected directly to the input data define relatively simple concepts/probability distributions, while later neurons combine these simple concepts/distributions into more complex ones. In the figure, the far-right neuron’s concept is the union of the other two – it is represented by any vector that represents one or the other.

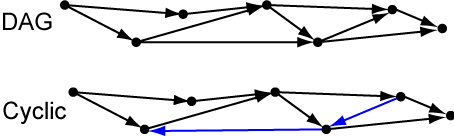

Implicit in this definition is the idea of a Directed Acyclic Graph, or DAG: Directed means that each edge in the network/graph has an arrow on it, pointing from a neuron whose output is used to the neuron that uses it. Acyclic means that if you follow these arrows, you can never go in a loop – all paths must move away from the input features and eventually make it to the output of the entire network, as with the top graph in the figure below.

If you can follow the edges of a directed graph and get back to a vertex that you already visited, this is called a cycle. Notice how the two blue edges in the bottom graph create cycles. These are problematic for neural networks because when you calculate the output of a neuron, you need to know the outputs of all the neurons that point into it. If there’s a cycle, there’s no neuron that you can calculate first, before all the other neurons. In the graph above, you could reorder the vertices so that the blue edges point to the right, but then some of the other edges would have to point left.

Whenever you do have a DAG, you can order the vertices (neurons) so that all the edges pointing into each vertex come from earlier vertices, i.e. all the edge point to the right. If you order the neurons in a standard neural network like this, you can calculate the outputs of the neurons in this order and know all the values needed to calculate each neuron’s output by the time you get to it.

A recurrent neural network is a neural network that is not a DAG. So as noted above, there’s no natural order on the neurons in which all the arrows point forward. But, then, how do we calculate the output values of the neurons?

It turns out the best thing to do is to carry on, pretending that there’s nothing wrong. In particular, we start by picking an ordering for the vertices, dropping the condition that the arrows defined by the edges have to point towards later vertices. This ordering will allow us to calculate the output values of all the neurons for a given input vector – for each neuron in the sequence, we use the output values from the earlier neurons that have already been calculated, and treat the outputs from the later neurons as if they were set to zero or some other default value.

But then what’s the point of the arrows that point backwards? Well, remember that the goal of recurrent neural networks is to deal with sequential data, in which we get one vector after another. For example, if we’re analyzing text, we might use bag-of-words with a moving window – use the first five words for the first vector, the second through the sixth word for the next vector, then the third through seventh and so on.

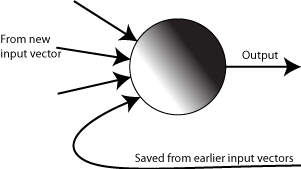

When we process the first vector, we do exactly what we described above – using a default value for the output of any neuron with an arrow that points “backwards” in the ordering. But then, when we process the second vector and get to a neuron with an arrow pointing backwards, we discover that we now have an output value for it – the value that was set when we processed the first input vector. So the neuron output values determined by the second vector in the sequence are affected by the first vector in the sequence. We repeat this for the third input vector, ending up with output values that are affected by the first two input vectors as well. So the backward arrows function kind of like memory cells within the recurrent neural network, remembering which “concepts” the earlier inputs represented.

Now, there are other, simpler ways we could create a model that takes into account more than one of these moving window vectors at a time. For example, we could concatenate the first N of the vectors together for some N, creating an input vector with N times as many dimensions as we started with. This is similar in principal to an n-gram. This would put the input back in standard vector form, so we could use any old model on it.

A recurrent neural network is a more complex solution than this, but it has two big advantages over techniques like n-grams or this concatenation scheme: First, the recurrent neural network works the same way no matter how long the sequence of inputs is. In other words, you don’t have to choose a value N before you start using it.

Second, and perhaps more importantly, a recurrent neural network reuses the same neurons for all the inputs in the sequence, allowing the overall network to be smaller/simpler. As each input vector comes in, it gets “compressed” into a set of concepts, defined by the neurons whose output will feed back into the next cycle of the network.

Any scheme for turning a sequence into a vector would need to use some method to reduce the number of dimensions, such as restricting to the most common n-grams. The recurrent neural network does this implicitly, as part of the same training process (whose description will have to wait for a later post) as the rest of the network. So the process is much more natural, and doesn’t require as many arbitrary decisions.

Like this:

Like Loading…

Related