|

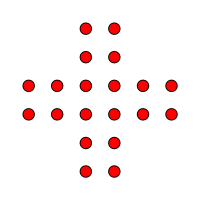

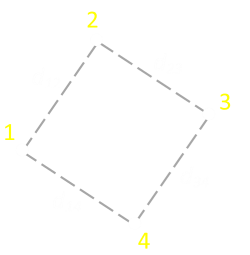

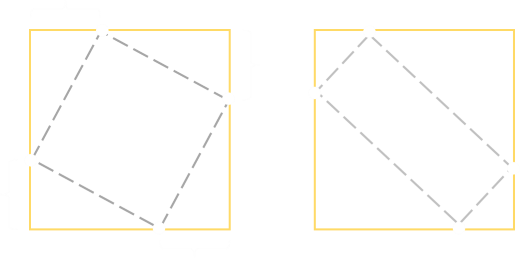

Here’s a fun little puzzle. There are twenty pegs arranged on a square grid, configured into the shape depicted on the left.The goal is to remove six pegs from the board such that, of the remaining pegs, no four of them can be used to form the corners of a square.Question: Which pegs should you remove? |

The goal is to remove six pegs from the board such that, of the remaining pegs, no four of them can be used to form the corners of a square.

Solving

This is a pretty fun little puzzle, and one that is small enough in scope that you might be able to solve it with a piece of paper. It’s also small enough in scope that you can, if needed, simply brute force an answer to permute through all possible combinations and test these.

There are a couple of things you have to watch out for. The first is you need to reject solution that leave four pegs that form the corners of a unit square; this is pretty easy to test for. Next, you might need to consider if four points could be used to make a bigger square (which if they are parallel to the grid, for this puzzle, is not possible); again, not too much of a challenge. However, there is also the issue of what to do about squares of varying sizes that are constructed at angles.

How do you determine if any four points describe the vertices of an arbitrary square?

This is the meat, and the main part of this posting. How do you test for squares?

Testing for squares

| |If we have four points, defined by four pairs of coordinates, how do we determine if they could possible make a square?First, let’s go back to basics. How is it possible for four vertices to be connected? A four pointed shape also has four sides and is given the mathematical term of quadrilateral.|

|If we have four points, defined by four pairs of coordinates, how do we determine if they could possible make a square?First, let’s go back to basics. How is it possible for four vertices to be connected? A four pointed shape also has four sides and is given the mathematical term of quadrilateral.|

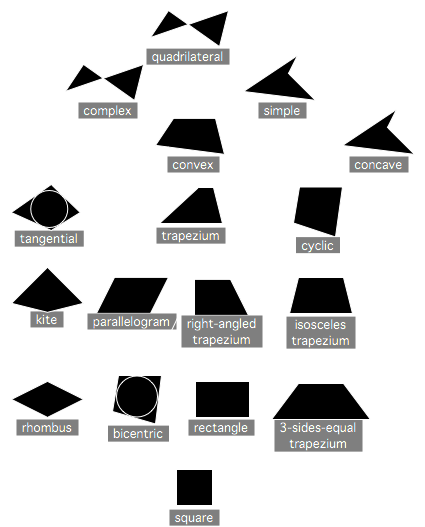

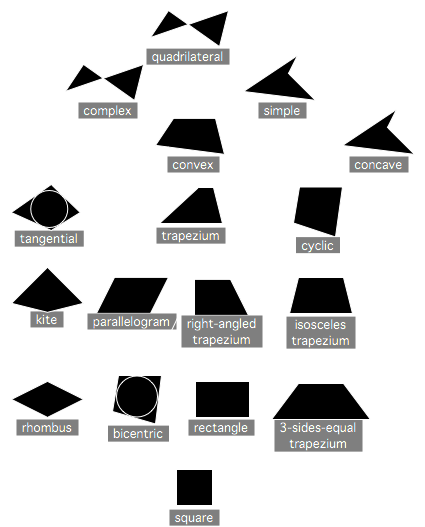

First, let’s go back to basics. How is it possible for four vertices to be connected? A four pointed shape also has four sides and is given the mathematical term of quadrilateral.

Some quadrilaterals have symmetry, some have other points of interest, some have nothing interesting about them. Below is a family tree showing all formal definitions of quadrilaterals, and their properties.

First thoughts

| |First thoughts - How about if we test the distance between pairs of points? After all, the sides of a square are all the same length. Can we just test that all these lengths are the same?d12 = d23 = d34 = d14|

|First thoughts - How about if we test the distance between pairs of points? After all, the sides of a square are all the same length. Can we just test that all these lengths are the same?d12 = d23 = d34 = d14|

Well, no. There are couple of problems with this solution The first is that squares are not the only quadrilaterals that have same length sides. This test will give out false positives against a rhombus.

The next problem with this solution is that the points might not be provided in rotationally correct directed order. If just given four points, and they are taken in the ‘correct’ order they will make a simple polygon. If they are taken in a different order, even if the points are ‘square’, a complex polygon could be generated, and the edges will not be the all same length (giving an incorrect answer). There are various algorithms that can be used to order the points into the correct directed order, but that does not solve the rhombus issue.

Second idea

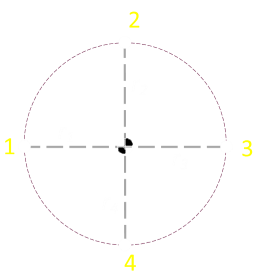

| |How about calculating the centroid of the points? If we calculate the centroid of all four vertices, can we not test to make sure each corner is the same distance of away from the centroid?r1 = r2 = r3 = r4|

|How about calculating the centroid of the points? If we calculate the centroid of all four vertices, can we not test to make sure each corner is the same distance of away from the centroid?r1 = r2 = r3 = r4|

Well, that’s good a test, but if all you do is this test, it only proves is that the four points are on a circle. To make sure they are in a square you’d also need to test the distance between vertices around the edge too (as above).

Alternatively, if you determine the vector from the centroid to one vertex you can then simply rotate this around 90° three times, checking each time it corresponds with another vertex.

What other ideas can we try?

Right Angles

| |If we know the points are in cyclic order, and once we’ve tested the four lengths are the same, then we can test the angle at one corner. It does not matter which corner we choose; if all four sides are the same length then if one corner is 90°, then all other corners will be right-angles too, and we’ve proved we have a square.A simple test if a corner is a right angle is to calculate the dot product of the vectors between the corner and the two adjacent corners. If the dot product is zero, the vectors are orthogonal.A hybrid version of this algorithm is to confirm the dot product of two vectors in a corner is zero, then add in the vectors of the two unused edges and you should get to the coordinate of the opposite corner.|

|If we know the points are in cyclic order, and once we’ve tested the four lengths are the same, then we can test the angle at one corner. It does not matter which corner we choose; if all four sides are the same length then if one corner is 90°, then all other corners will be right-angles too, and we’ve proved we have a square.A simple test if a corner is a right angle is to calculate the dot product of the vectors between the corner and the two adjacent corners. If the dot product is zero, the vectors are orthogonal.A hybrid version of this algorithm is to confirm the dot product of two vectors in a corner is zero, then add in the vectors of the two unused edges and you should get to the coordinate of the opposite corner.|

A simple test if a corner is a right angle is to calculate the dot product of the vectors between the corner and the two adjacent corners. If the dot product is zero, the vectors are orthogonal.

Rotating

| |If you want to dig out trigonometry, you could find the gradient of one side and rotate the shape so that this edge lines up with a coordinate axis. This would make the math easier to test for squareness.|

|If you want to dig out trigonometry, you could find the gradient of one side and rotate the shape so that this edge lines up with a coordinate axis. This would make the math easier to test for squareness.|

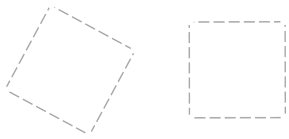

Bounding Box

| |Related to the above, it’s possible to generate a bounding box around the test shape by checking the min and max coordinates in the x-axis and y-axis.However, this test, again, is not distinct enough for squareness (it’s possible to generate geometries that cause false positives).|

|Related to the above, it’s possible to generate a bounding box around the test shape by checking the min and max coordinates in the x-axis and y-axis.However, this test, again, is not distinct enough for squareness (it’s possible to generate geometries that cause false positives).|

However, this test, again, is not distinct enough for squareness (it’s possible to generate geometries that cause false positives).

As with the above solutions the edges need to be tested to check to see if they are same length (or you can show the lengths from the bounding box corners are the same).

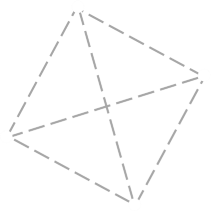

Six edges

| |An easy to implement algorithm (that does not require the points to be in correct simple order) is to simply calculate the distances between all pairs of points. With four vertices, there are six distances.If the four points are a square, there should be four equal ‘short’ lengths and two larger equal ‘long’ lengthsIt’s not strictly necessary, but you can also check that the ratio between the four short lengths and the two longer lengths is √2.|

|An easy to implement algorithm (that does not require the points to be in correct simple order) is to simply calculate the distances between all pairs of points. With four vertices, there are six distances.If the four points are a square, there should be four equal ‘short’ lengths and two larger equal ‘long’ lengthsIt’s not strictly necessary, but you can also check that the ratio between the four short lengths and the two longer lengths is √2.|

If the four points are a square, there should be four equal ‘short’ lengths and two larger equal ‘long’ lengths

Optimisations and gotchas

| |When calculating distances you can use Pythagoras (Δx2 + Δy2), but there is no need to perform the square-root at the end. Comparing the squared distances is just a good. This will save a few processor cycles.The chances are you will be using floating point to calculate the distances. Because of the potential of rounding errors, it is a bad practice to compare these distances directly. Instead calculate the absolute value of their differences and check to see if this is below a small threshold value.If you implement the six edges algorithm, there are various ways that it is possible to break from the algorithm early. For instance, as you are calculating the distances between pairs of vertices, if you come up with more than two distinct lengths you can exit immediately.|

|When calculating distances you can use Pythagoras (Δx2 + Δy2), but there is no need to perform the square-root at the end. Comparing the squared distances is just a good. This will save a few processor cycles.The chances are you will be using floating point to calculate the distances. Because of the potential of rounding errors, it is a bad practice to compare these distances directly. Instead calculate the absolute value of their differences and check to see if this is below a small threshold value.If you implement the six edges algorithm, there are various ways that it is possible to break from the algorithm early. For instance, as you are calculating the distances between pairs of vertices, if you come up with more than two distinct lengths you can exit immediately.|

The chances are you will be using floating point to calculate the distances. Because of the potential of rounding errors, it is a bad practice to compare these distances directly. Instead calculate the absolute value of their differences and check to see if this is below a small threshold value.

Back to the original puzzle. Here are the eight solutions to the twenty peg puzzle:

If you look closely, you’ll notice it’s really just one solution that is rotated and reflected!

You can find a complete list of all the articles here. Click here to receive email alerts on new articles.

Click here to receive email alerts on new articles.