||

| |

|

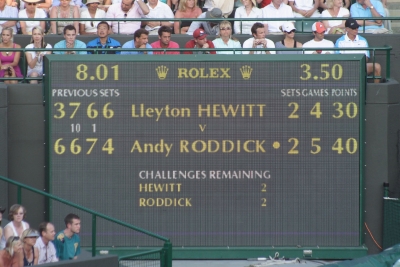

What is the probability winning a tennis match?

Your chance, obviously, depends on the relative ratio of your skill at the sport compared to that of your opponent.

Let’s define p to represent the probability that you’ll win any individual point. From this, it’s clear that the probability you will lose any point is (1-p).

If a match consisted of just one point, the probability of you winning a match would be the same as you winning just one point. However, as a match of tennis contains many point battles, and tennis has some quirky score advancing rules; these concentrate the advantage that a more skillful player has to win the match.

Simplifications

| |For this analysis I’m going to assume that the probability remains fixed throughout the entire game (no fatigue/stamina modifications), and I’m ignoring any advantage associated with serving. I’m also ignoring any psychological pressure associated with match-points, or catch-up. In this way I can keep the analysis fairly ‘simple’ in that I don’t need to keep track of state. At every point, I’m assuming the probability you’ll win that point is just p.|

|For this analysis I’m going to assume that the probability remains fixed throughout the entire game (no fatigue/stamina modifications), and I’m ignoring any advantage associated with serving. I’m also ignoring any psychological pressure associated with match-points, or catch-up. In this way I can keep the analysis fairly ‘simple’ in that I don’t need to keep track of state. At every point, I’m assuming the probability you’ll win that point is just p.|

Game, Set, and Match

A tennis match consists of points, games, and sets. If you are not familiar with the rules of the game, here is a refresher.

Let’s see how your chance of winning a point fashions your chances of winning an individual game …

Games

Despite the quirky “Love-15-30-40” nomenclature used in tennis to record the score state, to win a game of tennis, a player needs to win four points. The complication is that he/she can’t win by just one point; it must be at least two points. For most of the scoring combinations this happens automatically, but if the players tie at 40-40, called “Deuce” (essentially at three points each), a player can only win by scoring two consecutive points. Rather than having to keep track of (potentially) large numbers, instead of constantly incrementing scores, once deuce is reached, the player scoring the next point has ”Advantage”. If they win the subsequent point, they win the game. If they lose that point, the score returns back to deuce, and the battle starts afresh.

We’ll come back to deuce in just a second, but first let’s look at all the possible score combinations to win a game:

40-0

This score is the total whitewash. You win every one of the four points in the game. If the probability you win one point is p, the probability you win four points is p×p×p×p.

40-15

The next case is if you win the game 40-15. Here you need to win the last point (probability p), and also any three of the previous four points. The probability of you winning three of the last four is p3(1-p), and there are 4C1 ways this can be achieved.

40-30

The next case is a win 40-30. Similar to above, by definition, you need to have won the last point to win (probability p), and also any three of the previous five points (your opponent having won two of them). There are 5C2 ways that this latter part can be achieved.

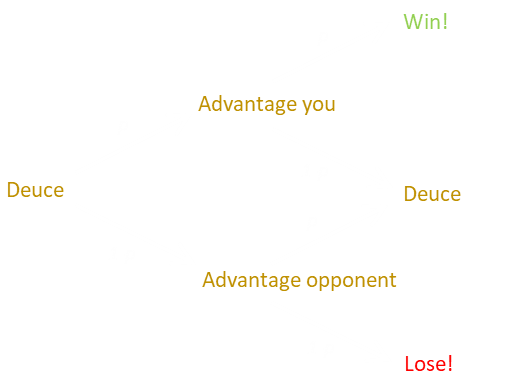

Winning from 40-40

This is the “Deuce” case. This is a little more complicated. First, let’s take a quick look at the probability of getting to Deuce. To initially get to deuce, each player needs to get three points.

Next we need to determine the probability of a winning from the deuce. We’ll define this probability as d, so the probability of winning a game that has gone through a deuce is:

Deuce

Here’s a graph of what could happen after a game gets to deuce. A player could win both of the next points p2, and win the game. They could lose both points, and lose the game (1-p)2, but if they win-lose, or lose-win, they get back to where they started, and where there is still a d percentage chance of a win. So, we can describe the probability in a self-referential way, and rearrange.

The probability, d, of winning from deuce is thus:

Inserting this into the probability of winning via a deuce we get:

Putting it all together

Adding up all the possible ways to win a game:

Pr(Game)=Pr(40-0) + Pr(40-15) + Pr(40-30) + Pr(40-40)d

Plugging in the individual equations:

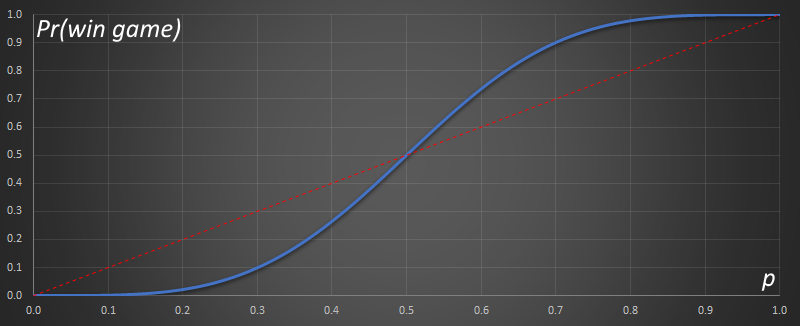

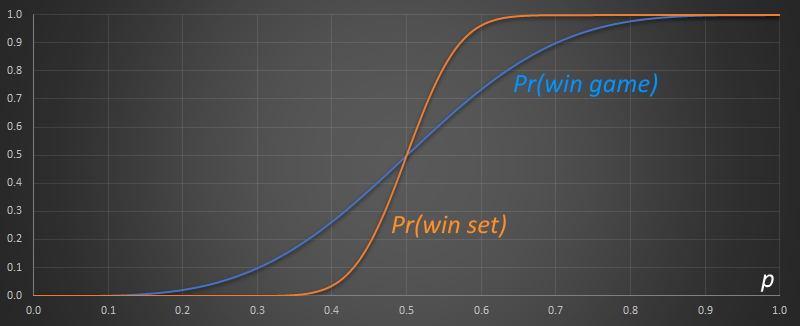

Here is the equation plotted.

The blue line shows the probability of winning a game of tennis based on your probability of winning a point. As you can see the curve is rotationally symmetric around p=0.5 (which is what we’d expect). The red line, for reference, is the identity line where the Pr()=p.

As the probability moves further away from p=0.5, the leverage increases (because a slight advantage to win a single point amplifies to make winning the four points to win a game much easier). By the time p=0.7, the probability of winning a game is over 90%.

Sets

In tennis, a number of games form a set. A set is won by the first player to win 6 games with a margin of at least 2 games. If a set gets to 6-6, then a tie-breaking process kicks in (more on this later).

Similar to our analysis of the games, let’s look at all the ways a player can win a set.

We’ll define the probability of winning a game (that we just calculated above) as w to simplify the math.

6:0

Again, this is a whitewash. This is where you win every single game in the set. If the probability of winning a game is w, then the probability of winning a set 6:0 is w×w×w×w×w×w

6:1

To win a set 6:1, you need to have won the last game (by definition), which is probability w, and then any five of the previous six games. The probability of winning a game is w and losing is (1-w), and there are 6C1 ways these games can be arranged.

6:2

There are two ways to win a set 6:2

You can either win the last two games, having won four of the previous six …

… or you can win the last game, having lost the one previous, but won five of the first six.

6:3

There are three ways to win a set 6:3

-You can win the last three games, having won three of the previous six (and lost three).

-You can win two of the last three games (making sure the very last game was a win), having won four of the first six games.

-You can win the last game, having lost the previous two, and won five of the first six games.

6:4

There are four ways to win a set 6:4

-You can win the last four games, having won two of the first six.

-You can win three of the last four games (ensuring the last game is won), plus three of the first six.

-You can win two of the last four games (ensuring the last game is won), plus four of the first six.

-You can win the last game, having lost the previous three, but five of the first six.

7:5

This set score is a little subtle. The only way to get to win with a score of 7:5 is having passed through 5:5, and won the next two games. If you don’t win both games, then the set turns into a tie-break (and we’ll look at the fun math associated with that in the next section).

The probability of 5:5 is easy the calculate, and then all we need to do is multiply this by w2 for the probability of winning the last two games.

7:6 (and the tie-break)

The last case we need to deal with is the gnarly tie-break ruling. If a game gets to 6:6 then, according to the original rules of tennis, play would continue until one player was able to get two games ahead to win the set. This resulted in games that went on, and on, and on. Sometimes taking hours just to finish a set (or matches that spanned days!) To address this, the tie-break rule was enacted (sometimes called the “twelve point tie-breaker”).

In a tie-break, only one more game is played to determine the winner of the set. Points are counted using ordinary numbering. The set is decided by the player who wins at least seven points in the tie-break but also has two points more than his or her opponent (The set is then placed on the scoreboard as 7:6 with a superscript addition of the losing players count. From this the winners score can always be determined. For instance 7:6(10), the tie-break score was 12-10, as the winner needs to have won by two points. Similarly a score of 7:6(3) means the tie-break score was 7-3, as the winner needs to have scored at least seven points).

| |*In Wimbledon, and now The Davis Cup (and probably others), the tie-break rule does not apply on the final set. If the game is tied, and the final set gets to 6:6, play continues until one player is ahead by two games. I’m going to ignore this tie-break override in my analysis.|

|*In Wimbledon, and now The Davis Cup (and probably others), the tie-break rule does not apply on the final set. If the game is tied, and the final set gets to 6:6, play continues until one player is ahead by two games. I’m going to ignore this tie-break override in my analysis.|

First of all, we need to calculate the probability of getting to a score of 6:6.

Again, this is subtle, because the only way to get to 6:6 is from 5:5 and each player winning one game (any other scoring would have resulted in a win for one of the players before getting to 6:6). We previously calculated Pr(5:5), and to get to Pr(6:6) requires either a win and a loss, or a loss and a win.

Now we know Pr(6:6), the probability of winning 7:6 is:

Where t is the probability of winning the tie-break. Which we now need to calculate …

Tie-break calculation

Hold onto your hats, we’re almost there, but the numbers get a little involved. The principle is the same, we simply need to work out the chances of winning the tie-break for all possible combinations of score.

The chance of winning the tie break game is the chance of winning with a score of 7-0 plus the chance of winning with a score of 7-1, plus a chance of winning with a score of 7-2 … up to winning 7-5. The final wrinkle is if the tie-break score gets to 6-6, this turns into an identical problem as the deuce issue, of needing to least a two point lead (which we’ve solved already!)

Take a deep breath …

Which sums to:

(Where d is the probability of winning from deuce, as calculated earlier).

Returning to Sets

We now have all the components needed to determine the probability of winning a set based on the probability of winning a point.

We’ll call this s.

s = Pr(6:0) + Pr(6:1) + Pr(6:2) + Pr(6:3) + Pr(6:4) + Pr(7:5) + Pr(7:6)

Graphing this out results in the following curve. You can see that the probability of winning a set is even more sensitive to probability of winning a game.

To get to a 90% chance of winning a set, the value of p only needs to be above 0.57, and any value of p over 0.63 gives a greate than 99% chance of winning the set.

Match

Finally, things get even more concentrated as a match of tennis (for mens and doubles), is awarded to the winners of the best of five sets. The first player to win three sets, wins the match.

There are three ways that a player can win best of five sets:

-The player can win the first three sets.

-The player can win the last set, and two of the previous three (game over in four sets).

-The player can win the last set, and two of the previous four (game over in five sets).

If we define m to the probability of winning a match, we can derive is from the probability of winning a set s.

Results

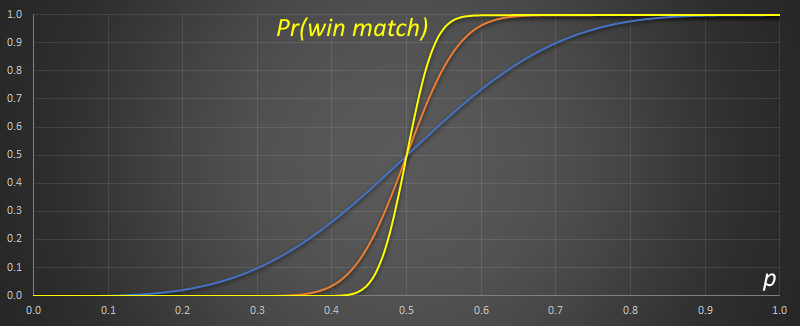

Plotting this out we can see how the probability of winning the entire match is even more sensitive to p.

Here is the data in tabular format for a small section close to p=0.5

It shows the probabilities of a player winning a game, set, or match based on p.

| p | Game | Set | Match |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.40 | 0.264271 | 0.036567 | 0.000463 |

| 0.41 | 0.285501 | 0.053368 | 0.001401 |

| 0.42 | 0.307438 | 0.075782 | 0.003872 |

| 0.43 | 0.330020 | 0.104746 | 0.009763 |

| 0.44 | 0.353182 | 0.141002 | 0.022439 |

| 0.45 | 0.376851 | 0.184958 | 0.047018 |

| 0.46 | 0.400952 | 0.236570 | 0.089862 |

| 0.47 | 0.425403 | 0.295262 | 0.156868 |

| 0.48 | 0.450120 | 0.359895 | 0.250730 |

| 0.49 | 0.475015 | 0.428821 | 0.368331 |

| 0.50 | 0.500000 | 0.500000 | 0.500000 |

| 0.51 | 0.524985 | 0.571179 | 0.631669 |

| 0.52 | 0.549880 | 0.640105 | 0.749270 |

| 0.53 | 0.574597 | 0.704738 | 0.843132 |

| 0.54 | 0.599048 | 0.763430 | 0.910138 |

| 0.55 | 0.623149 | 0.815042 | 0.952982 |

| 0.56 | 0.646818 | 0.858998 | 0.977561 |

| 0.57 | 0.669980 | 0.895254 | 0.990237 |

| 0.58 | 0.692562 | 0.924218 | 0.996128 |

| 0.59 | 0.714499 | 0.946632 | 0.998599 |

| 0.60 | 0.735729 | 0.963433 | 0.999537 |

|

It’s pretty amazing how steep the match curve is. The moral of this story is: don’t attempt to play a game of tennis with anyone who is not pretty close to the same level of skill as yourself!If your opponent is even slightly better than you are, you’ll really struggle to win. |

If your opponent is even slightly better than you are, you’ll really struggle to win.

You can find a complete list of all the articles here. Click here to receive email alerts on new articles.

Click here to receive email alerts on new articles.